Space Asset under the Space Protocol of the Cape Town Convention

By Pai Zheng

Pai Zheng is currently a student of East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPL) of Shanghai, China. He holds a LL.M. of advanced studies in Air and Space Law from Leiden University and a LL.M. from ECUPL with a specialization in International Law.

Published November/December 2014

Abstract

Nowadays more and more space equipment is financed by private entities, and these ongoing privatization and commercialization of space industry creates more financial risks for the private sector financers. At the same time, the movable nature of space activities may cause legal uncertainties of the security interests. Given such situation, the 2001 Cape Town Convention and the 2012 Space Protocol marked a significant development in harmonizing and unifying the rules on asset-backed finance for mobile equipment. As a core term in the Space Protocol, the concept of Space Asset was for the first time introduced in and defined under the Space Protocol, which may cause potential impact on the contemporary international space law. This paper first explains and examines the definition of Space Asset, then further discusses issues related to this new concept, including the delimitation issue, the relationship between an Aircraft Object and a Space Asset, as well as the difference and similarity between a Space Asset and a Space Object under the UN space treaties.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that the development of space industry requires huge investments, e.g., a fully operational reusable launch vehicle with modern technology may cost USD 10 billion.[1] Except for governmental investment, nowadays more and more space equipment is financed by private entities, such as banks, investment companies, insurance companies, and other financial institutions. Accompanying with the increasing privatization and commercialization of space activities, these ongoing developments of space industry create more financial risks for the private sector financers. The probability for the creditors (i.e., the financiers) to be repaid is lower than before, since their investment risk is no longer assumed by States or the governments. Therefore, these investment activities, especially for the asset-based financings, need to be protected and stabilized under law.

However, mobile equipment such as a satellite is highly movable by its very nature, and it may keep crossing national borders or operate outside sovereign territory during its lifetime. This movable nature may cause legal uncertainties when a security interest is created on a cross-border space equipment through asset-based financing, as which domestic law shall apply to regulate the security interest is questionable. Therefore, the concern is raised at an international level, in so far as there is no clear answer for whether the security interest created under the domestic laws of State A is still valid and enforceable in State B or other States. Given such situation, the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (the Cape Town Convention)[2] adopted in 2001, together with the Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on Matters Specific to Space Assets (the Space Protocol)[3] adopted in 2012, marked a significant step forward in harmonizing and unifying the rules of national laws on the subject of asset-backed finance for mobile equipment.[4] Prior the adoption of the Space Protocol, the validity of security interest could depend on several different factors such as national laws of different States, or bilateral arrangements between certain State A and B.[5]

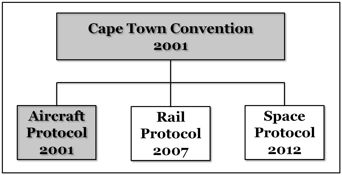

The whole Cape Town Convention regime, as illustrated in Figure I with the documents in force marked in grey, is structured as a main convention (i.e., the Cape Town Convention itself) with three different protocols which deal with three kinds of different movable equipment assets, namely the Aircraft Protocol (2001)[6], the Rail Protocol (2007)[7] and the Space Protocol (2012). Pursuant to the Cape Town Convention, each specified Protocol shall be read and interpreted together with the Convention as a single document, and in case that there is any inconsistency between the Convention and the Protocols, the Protocols shall prevail.[8] At this moment only the Cape Town Convention (with 62 Contracting States) and the Aircraft Protocol (with 56 Contracting States) have entered into force.[9]

Figure I

This paper mainly focuses on the concept of the “Space Asset” which was for the first time introduced in and defined under the Space Protocol of the Cape Town Convention, as well as the potential impact of this new concept on international space law. The second section of this paper explains and analyses the definition of the Space Asset, and the third section further discusses issues related to the Space Asset, including the related delimitation issue, the relationship between Space Asset and Aircraft Object, and the relationship between Space Asset and Space Object of the UN space treaties.[10]The last section concludes the study and provides certain comments.

2. Description of Space Asset under the Space Protocol

2.1 Definition of Space Asset

The Cape Town Convention mentioned the concept of Space Asset for the first time under its Article 2(3) (c) without defining it, and it is the Space Protocol that provides the full definition of the Space Asset.[11] According to the Protocol, a Space Asset is defined as any man-made uniquely identifiable asset in space or designed to be launched into space, and comprising:

- (a) a spacecraft, such as a satellite, space station, space module, space capsule, space vehicle, or reusable launch vehicle, whether or not including a space asset falling within (b) or (c) below;

- (b) a payload (whether telecommunications, navigation, observation, scientific or otherwise) in respect of which a separate registration may be effected in accordance with the regulations; or

- (c) a part of a spacecraft or payload such as a transponder, in respect of which a separate registration may be effected in accordance with the regulations, together with all installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto.[12]

The term “Space” in “Space Asset” refers to outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, which is consistent with international space law.[13] Also it is of great importance to mention that the Space Protocol shall not apply to objects falling within the definition of Aircraft Objects under the Aircraft Protocol, except where such objects are primarily designed for use in space, regardless of its actual position is in space or not.[14] Moreover, the Space Protocol shall not apply to an Aircraft Object merely because it is designed to be temporarily in space.[15] Such provisions are aiming to avoid potential overlap and contradiction between the Space Protocol and the Aircraft Protocol.[16]

2.2 Analysis of the Definition

Pursuant to the aforementioned complicated definition and description of Space Asset, there are certain requirements that must be fulfilled for a space equipment or object to be treated as a Space Asset under the Space Protocol.[17] The requirements for constitution of a Space Asset are explained as follows:[18]

First, the object or equipment must be man-made, i.e., minerals or asteroids from the moon or other celestial bodies are unlikely to be treated as Space Assets under the Protocol, even if they are high-valued. However, if the natural resource from space is transformed through human activities into new material or object, the transformed object can be seen as a Space Asset according to the Protocol.[19]

Second, the object or equipment must be uniquely identifiable under the Cape Town Convention regime. The Convention states that for a security interest constituted as an international interest, the related agreement shall enable an asset or object are identified in conformity with the Protocol.[20] In fact, the Space Protocol provides that a description of a Space Asset is sufficient to be identifiable if it contains one or more of the following elements:

- a description of the space asset by item;

- a description of the space asset by type;

- a statement that the agreement[21] covers all present and future space assets; or

- a statement that the agreement covers all present and future space assets except for specified items or types.[22]

These descriptions for identifiable requirement provided by the Space Protocol are rather vague, generic and open-ended, especially in comparison with the Aircraft Protocol. The latter requires more specific descriptions such as manufacturer’s serial number, name of manufacturer, and model designation.[23] This vagueness may cause practical problems in relation to the international registration system.

Third, the object or equipment must be

- in space; or

- designed to be launched into space.

This means that the Protocol adopted both the “spatialism” approach, i.e., the object is literally located “in” space, and the “functionalism” approach, i.e., the purpose or aim for the object is space oriented regardless of its actual position, which broadened the scope of the Space Asset. It covers not only an object or equipment already in space, but also an object or equipment which has not yet been launched, e.g., under manufacturing, in storage, en route for launching, or on the launch pad, etc., as long as the object or equipment has been designed to be launched into space.[24]

Forth, the object or equipment must be

- a spacecraft, whether or not including a separate registered space asset;

- a payload which is separately registered; or

- a part of a spacecraft or payload, together with “attachments” which include:

- (a) all installed, incorporated or attached accessories; and

- (b) parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto.

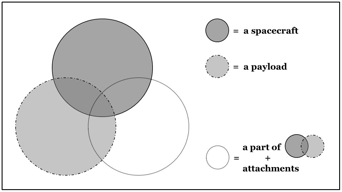

The illustrated examples in the Space Protocol, e.g., a reusable launch vehicle or navigation payload, are not exhaustive. However, it is supposed that these Space Assets are high-valued ones. It is worth mentioning that Space Asset also covers all the “attachments” related to the spacecraft or payload as widely as possible, even including data, manuals and records.[25] Besides, the payload and spacecraft may have certain overlapping areas, e.g., a satellite can be deemed to be both a spacecraft and the payload of a rocket on which it was launched.[26] The relationship between the aforementioned items is illustrated as follows in Figure II.

Figure II

Fifth, in order to be a Space Asset, the object, equipment or related part must be separately registrable according to the regulations governing the registration of international interests in Space Assets.[27] This registration requirement is different from the State obligation under the 1975 Registration Convention since here it is the security interests created on the Space Assets are under concern. A Supervisory Authority pursuant to the Protocol shall create an international registry system.[28]

3. Issues Related to Space Asset under International Space Law

3.1 Related Delimitation Issue

The delimitation of space is relevant here because in defining the term Space Asset, the Protocol mentioned “in space”. Without a clear answer to this question, i.e., where outer space begins, it is also not clear whether an object or equipment can be qualified as a Space Asset when it is located below an altitude of 100 kilometers (the Kármán line), in an altitude of 100 kilometers, in sub-orbital area which may reach 105 kilometers, in orbit or beyond orbit.[29] However, this problem may not be as serious as it appears, in so far as the Protocol also provided a parallel approach of “designed to be launched into space”. Although one could argue that here “into space” still needs clearance and definition, my view is that what is important here in this phrase is “designed to be…”, which provides an opportunity to bypass the unsettled delimitation issue that may keep unsettled for a long time.

The “designed to be…” can be interpreted as a functionalism approach for defining Space Asset, i.e., as long as the purpose, aim or objective of an object or equipment is designed as space-oriented and not as aircraft-oriented, the object or equipment is qualified to be a Space Asset, provided that all the other requirements under the Protocol are fulfilled. It is quite clear that “designed to be launched into space” does not require the object or equipment to be actually “located in” or “launched into” space, whatever how to define “space”. Furthermore, this approach even allows the attachments of an object or equipment to be qualified as Space Assets without actually launching or manufacturing the relevant object.[30] Therefore, my opinions on this issue are as follows:

- It is difficult to define a Space Asset according to the phrase “in space” under Article I(2)(k) of the Space Protocol, since there is no internationally recognized definition of “space” or “outer space” and the Protocol does not provide a definition; however,

- The problem can be solved under the Space Protocol itself since Article I(2)(k) of the Protocol also provides a separate approach in defining Space Asset by function, which can circumvent the impasse of the delimitation debate.

3.2 Space Asset v. Aircraft Object

As mentioned before, the Space Protocol is not applied to an object or equipment falling within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol, and it is not applied to an Aircraft Object which is designed to be temporarily in space. The only exception is that an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in space and thus can be treated as a Space Asset de facto.[31] Thus, potential overlapping is possible on condition that an object or equipment both falling within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol and the condition of “primarily designed for use in space” under the Space Protocol.[32]

It should be noted that the Space Protocol does not state that an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in space “is” a Space Asset, it only provides that in that circumstance the Space Protocol will apply to that Aircraft Object.[33] Thus the object related retains its legal status as an Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol, which is at the same time treated as a Space Asset de facto. Therefore, the issue here is not really about the differentiation of an Aircraft Object and a Space Asset, but a question of in which condition the Space Protocol can apply to an Aircraft Object.

According to the Aircraft Protocol, an Aircraft Object is referred to as airframe, aircraft engine and helicopter,[34] and the “airframe”[35] and “aircraft engine”[36] are separately defined in detail, which is quite clear and practicable. In short, an object or equipment is qualified as an Aircraft Object if:

- It is certified by the competent aviation authority to transport;

- It has jet propulsion, turbine-powered, or piston-powered engine; and

- It has a capacity for at least 8 persons (5 persons as for the helicopter) including crew or goods more than 2750 kilograms (450 kilograms as for the helicopter).[37]

Actually, the problem here is not about defining an Aircraft Object, but how to decide the conditions listed in Article II[38] of the Space Protocol. If an object or equipment is qualified as an Aircraft Object, the Space Protocol is generally excluded; however, there are two situations to be examined for the applicability of the Space Protocol to that Aircraft Object:

- The Space Protocol applies to an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in space, even such object is not in space. It is clear that this condition is functionalism based approach since the position of the object is irrelevant, what is not clear is that the term “primarily” is quite vague and lack of shared understanding or interpretation. The phrase “designed ‘for use’ in space” already shows the purpose or objective of the object is a key element, while what is the meaning of the word “use” is not that clear either.

- The Space Protocol does not apply to an Aircraft Object which is designed to be temporarily in space. There is a slight difference in this condition, the phrase here is “designed to be temporarily in space” instead of “designed ‘for use’ in space” as mentioned above. This means that an Aircraft Object which is merely designed to stay a “short” time in space and not for use in space is excluded from the Space Protocol. Although the meaning of “temporarily” is undefined, one may argue that an object which is designed to transit from air to space should be excluded.[39]

Therefore, my short conclusions for this issue are that:

- In general an Aircraft Object is not governed by the Space Protocol even if it is designed to be temporarily in space;

- Potential overlapping[40] of the Aircraft Protocol and Space Protocol is possible on condition that an object or equipment both falling within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol and the condition of “primarily designed for use in space” under the Space Protocol; and

- The undefined words of “primarily”, “use” and “temporarily” are unclear under Article II of the Space Protocol. Given such situation, an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in space can be governed by the Space Protocol as if it is a Space Asset de facto, regardless of its actual position.

3.3 Space Asset v. Space Object

The new term of Space Asset defined in the Space Protocol is different from the term Space Object that has been used in several UN space treaties for a long time. However, for now there is no definition of Space Object and its meaning is unclear too. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty only mentions Space Object in Article X,[41] the 1968 Rescue Agreement mentions “Space Object or its component parts”[42], the 1972 Liability Convention and 1975 Registration Convention both mentions “launches or procures the launching of a Space Object” and explained that the term Space Object “includes component parts of a Space Object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof”,[43] and the 1979 Moon Agreement mentions “… in relation to the Earth, the Moon, spacecraft, the personnel of spacecraft or manmade Space Objects” and “a Space Object or its component parts”.[44] The other UN space law instruments also used the term Space Object without defining it.[45] As for the Space Asset, it is clearly defined in the Space Protocol as explained in the first section of this paper.

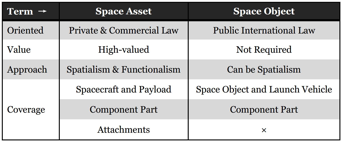

Pursuant to the Space Protocol, provisions of the Protocol together with the Cape Town Convention, do not affect the existing UN space treaties or instruments of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which means that where an object or equipment qualifies as both a Space Asset and a Space Object, the applicable UN treaty rules prevail.[46] But this only explains the relationship between the rules of the Space Protocol and UN space treaties, not the relationship between the two terms or concepts. In fact, at this moment there is no clear answer to this question and I believe the relationship between Space Asset and Space Object is quite complicated. However, I am trying to draw certain preliminary conclusions based on the ideas which back up these two terms, i.e., the purpose, motive, aim, or objective behind the two terms. In this sense, there are at least three main differences between the two terms or concepts, and the general relationship between the two terms is illustrated in Figure III below.

Figure III

- The Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention is private and commercial (especially asset-based financial) law oriented, while Space Object under the UN space treaties is public international law oriented. The purpose or motive for creating a concept of Space Asset is rooted in the practical need for asset-based finance on the mobile equipment, thus linked with private financial entities, i.e., the private financiers as creditors, which are mainly focus on the private security rights. On the other, the undefined term Space Object is linked to sovereign States and their international responsibility and liability. The Space Object is widely used in the 1968 Rescue Agreement, the 1972 Liability Convention and the 1975 Registration Convention, all of which clearly have State responsibility and liability concerns.

- The Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention is high-value oriented since by definition it is an asset, while Space Object under the UN space treaties does not have such concerns. This allows us to separate certain object which is not high-valued out of the scope of Space Asset, e.g., a non-reusable launch vehicle and space debris are not Space Assets, but both of them can be Space Objects. Moreover, certain kind of attachments such as date, records or manuals of the related space equipment are qualified as Space Assets, in so far as they have high values for the financier. However, these attachments on earth are hardly to be treated as Space Objects.

- The Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention adopted both of the spatialism and the functionalism approach in defining the term, while for Space Object it is more likely that the spatialism approach prevails. The Space Protocol clearly states that a Space Asset can be in space or designed to be launched into space. In the latter case, there is no need for the asset to be actually “located in” or “launched into” space, whatever how to define “space”. Therefore the position of a Space Asset is not that important, and it can be in space, en route, or on earth. For Space Object, the position of the object clearly matters although there is no clearance on this issue. This is because in many circumstances the 1972 Liability Convention and the 1975 Registration Convention have used the term Space Object under a potential background that the object related is literally located in space.

Except for the aforementioned differences, there are also some shared features of the two terms, which can be listed as follows:

- Both of them are involved with human efforts, i.e., man-made, although the words in 1979 Moon Agreement seem to imply the existence of certain non-man-made Space Object;[47]

- Both of them include component parts as well as the launch vehicle and parts thereof;

- There are overlapping areas for the two terms, e.g., a reusable launch vehicle is a Space Asset under the Space Protocol, and at the same time it is also a Space Object under the UN space treaties.

A simplified comparison between Space Asset and Space Object is illustrated in the following Figure IV.

Figure IV

4. Conclusions & Comments

General speaking, the Space Protocol is a significant step forward in harmonizing and unifying the rules of national laws on the subject of asset-backed finance for mobile equipment. However, so far it is unlikely to be welcomed by the industry, and especially opposed by space industry organizations such as the Satellite Industry Association (SIA).[48] The general opinion of industry is that the existing models and practice of space assets finance are sufficient and the Protocol has added an unnecessary supra-national layer of law to the financing industry.[49] One concern is that the definition of Space Asset is too vague in the Protocol.[50] Given such situation, I would still argue that the adoption of the Protocol provided potential impact on the financing industry as well as international space law, in so far as it created new legal terms and descriptions for the contemporary space activities. Despite its shortcomings such as the vague wording and missing definition on certain terms, the concept of Space Asset introduced in and defined under the Space Protocol of the Cape Town Convention is a huge development in contemporary international space law.

Certain comments related to this study can be listed as follows:

- It is not clear when a Space Asset would be considered in space since the debate of delimitation of outer space has not been resolved at international level; however, the problem can be solved under the Space Protocol since it adopted both the spatialism and the functionalism approach in defining the term, which may circumvent the impasse of the delimitation issue.

- In general an Aircraft Object defined under the Aircraft Protocol is not governed by the Space Protocol even if it is designed to be temporarily in space; however, given the fact that words of “primarily”, “use” and “temporarily” are not clear enough, an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in space can be governed by the Space Protocol as if it is a Space Asset de facto, regardless of its actual position.

- The main difference between Space Asset and Space Object is that the former is private and commercial law oriented, high-value oriented, and mainly linked to private financial entities, while the latter is public international law oriented and mainly connected with State responsibility and liability. There are also similarities and overlapping areas between the two concepts. Where an object or equipment qualifies as both a Space Asset and a Space Object, the applicable UN space treaty rules prevail.

[1] M. Van Pelt, Space Tourism: Adventures in Earth Orbit and Beyond, New York Copernicus Books 112 (2005).

[2] Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment, signed at Cape Town on 16 November 2001; hereinafter also referred to as Cape Town Convention.

[3] Protocol to the Convention on International Interest in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets, signed in Berlin on 9 March 2012; hereinafter the Space Protocol.

[4] The Cape Town Convention entered into force on 1 March 2006, and for now there are 62 contracting States; see UNIDROIT, STATUS – Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town, 2001), (http://www.unidroit.org/status-2001capetown), last visited (23.10.2014); The Space Protocol has not entered into force yet, and for now there are only 4 States which have signed the Protocol, namely Burkina Faso, Saudi Arabia, Zimbabwe, and Germany; see UNIDROIT, STATUS – UNIDROIT Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (Berlin, 2012), (http://www.unidroit.org/status-2012-space), last visited (23.10.2014).

[5] See Lutfiie Ametova, International interest in space assets under the Cape Town Convention, 92 Acta Astronautica 213, 213-214 (2013).

[6] Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment, signed at Cape Town on 16 November 2001; hereinafter the Aircraft Protocol.

[7] Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Railway Rolling Stock, signed in Luxembourg on 23 February 2007; hereinafter the Rail Protocol.

[8] See the Cape Town Convention Art. 6; see also the Space Protocol Art. II(2), which states that the Cape Town Convention and the Space Protocol shall be known as the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment as applied to space assets.

[9] See supra note 4; see also UNIDROIT, Status – Protocol to The Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment, (http://www.unidroit.org/status-2001capetown-aircraft), last visited (23.10.2014); and UNIDROIT, Status – Luxembourg Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Railway Rolling Stock (Luxembourg, 2007), (http://www.unidroit.org/status-2007luxembourg-rail), last visited (23.10.2014).

[10] There are five core UN space treaties, namely (a) Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Outer Space Treaty”), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2222 (XXI), opened for signature on 27 January 1967, entered into force on 10 October 1967; (b) Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Rescue Agreement”), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2345 (XXII), opened for signature on 22 April 1968, entered into force on 3 December 1968; (c) Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the “Liability Convention”), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2777 (XXVI), opened for signature on 29 March 1972, entered into force on 1 September 1972; (d) Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Registration Convention”), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 3235 (XXIX), opened for signature on 14 January 1975, entered into force on 15 September 1976; and (e) Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Moon Agreement”), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 34/68, opened for signature on 18 December 1979, entered into force on 11 July 1984; in general, see UNOOSA, United Nations Treaties and Principles on Space Law, (http://www.oosa.unvienna.org/oosa/en/SpaceLaw/treaties.html), last visited (23.10.2014).

[11] The Cape Town Convention simply mentioned that an international interest in mobile equipment is an interest in a uniquely identifiable object of a category of such objects as (a) airframes, aircraft engines and helicopters; (b) railway rolling stock; and (c) space assets. See the Cape Town Convention Art. 2.

[12] The Space Protocol Art. I(2)(k).

[13] The Space Protocol Art. I(2)(j).

[14] The Space Protocol Art. II(3); see also infra note 33.

[15] The Space Protocol Art. II(4); see also infra note 33.

[16] The related issue will be discussed in the third section of this paper.

[17] For a discussion of the early evolution of the term Space Asset in the Cape Town Convention, see S. Ospina, The Concepts of Assets and Property: Similarities and Differences, and Their Applicability to Undertakings in Outer Space, Proceedings of the Forty-Fifth Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (2003), vol. 12; O. M. Ribbelink, The Protocol on Matters Specific to Space Assets, 12 European Rev. Private L. 37, 39 (2004); and Z. Yun, Revisiting Selected Issues in the Draft Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on Matters Specific to Space Assets, 76 Journal of Air Law and Commerce 805, 814-815 (2011).

[18] For the conditions and requirements of Space Asset, see also Chunli Xia, On the Definition of Space Assets (Chinese), 13 (1) Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Science Edition) 79, 79-83 (2011).

[19] Mark J. Sunahl, The Cape Town Convention: Its Application to Space Assets and Relation to the Law of Outer Space (2013), at 35.

[20] The Cape Town Convention Art. 7(c); also the Space Protocol Art. V states that a contract of sale is one which: […] (c) enables the space asset to be identified in conformity with this Protocol; and the Space Protocol Art. IX states that a transfer of debtor’s rights is constituted as a rights assignment where it is in writing and enables: (a) the debtor’s rights the subject of the rights assignment to be identified; (b) the space asset to which those rights relate to be identified.

[21] The “agreement” here should be referred to as a security agreement, a title reservation agreement or a leasing agreement; see the Cape Town Convention Art. 1(a).

[22] The Space Protocol Art. VII(1); also the Space Protocol Art. VII(2) states that an interest in a future space asset identified in accordance with Art. VII(1) shall be constituted as an international interest, as soon as the chargor, conditional seller or lessor acquires the power to dispose of the space asset, without the need for any new act of transfer.

[23] See the Aircraft Protocol Art. VII.

[24] Supra note 19, at 35.

[25] It should also be noted that under the Protocol these data, manuals and records are separately registrable, which means that it is possible for the designing records of a satellite to be treated as Space Assets even if the satellite has not been made or is not able to be made in the future, as long as the unmade satellite is designed to be launched into space.

[26] Supra note 19, at 37.

[27] Ibid., at 50-51; see also the Space Protocol Chapter III – Registry Provisions Relating to International Interests in Space Assets, which provides the details for creating an international registration system.

[28] See the Cape Town Convention Arts. 16, 17; the Space Protocol Art. XXVIII.

[29] For the discussion on this issue, see also Lutfiie Ametova, International interest in space assets under the Cape Town Convention, 92 Acta Astronautica 213, 223, 225 (2013) and Mark J. Sunahl, The Cape Town Convention: Its Application to Space Assets and Relation to the Law of Outer Space (2013), at 36, 134-141.

[30] Supra note 25.

[31] Supra notes 14, 15.

[32] Before going into details, it is worth pointing out that the question of a specific object or equipment (such as a sub-orbital “spacecraft”) is deemed to be an Aircraft Object or a Space Asset or both, to some extent, is different from the general question of which law, i.e., air law or space law, will apply to an activity (such as a sub-orbital “flight”) that involved both international air law and space law. The former one is a specific question about determining the proper applicable rules for an object or equipment functioned as asset under and only under the Cape Town Convention regime, which has its main concerns about the asset finance. The concepts of Aircraft Object and Space Asset only function in the Cape Town Convention regime and financial transactions. While the latter question is a general question about the delimitation issue and establishing proper boundaries for air law and space law. This is not to say that there is no connection or similarity between the two questions, both questions are similar in so far as they both involve air law and space law, spatialist approach and functional approach, as well as have some overlapping areas; the questions are different in the sense that the former one is specifically asset-based and mainly focused on the object or equipment as an asset under the Cape Town Convention. Therefore, the difference between air law and space law is not the main focus of the Cape Town Convention, the necessity for dealing with this “air law or space law” issue is rooted in commercial and financial practice.

[33] The Space Protocol Art. II—Application of the Convention as regards space assets, debtor’s rights and aircraft objects—states that:

1. The Convention shall apply in relation to space assets, rights assignments and rights reassignments as provided by the terms of this Protocol.

2. […]

3. This Protocol does not apply to objects falling within the definition of “aircraft objects” under the Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters specific to Aircraft Equipment except where such objects are primarily designed for use in space, in which case this Protocol applies even while such objects are not in space.

4. This Protocol does not apply to an aircraft object merely because it is designed to be temporarily in space.

[34] The Aircraft Protocol Art. I(2)(c).

[35] Airframes means airframes (other than those used in military, customs or police services) that, when appropriate aircraft engines are installed thereon, are type certified by the competent aviation authority to transport:

(i) at least eight (8) persons including crew; or

(ii) goods in excess of 2750 kilograms,

together with all installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment (other than aircraft engines), and all data, manuals and records relating thereto. See the Aircraft Protocol Art. I(2)(e).

[36] Aircraft engines means aircraft engines (other than those used in military, customs or police services) powered by jet propulsion or turbine or piston technology and:

(i) in the case of jet propulsion aircraft engines, have at least 1750 lb of thrust or its equivalent; and

(ii) in the case of turbine-powered or piston-powered aircraft engines, have at least 550 rated take-off shaft horsepower or its equivalent, together with all modules and other installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto. See the Aircraft Protocol Art. I(2)(b).

[37] The Aircraft Protocol Arts. I(2)(a), (b), (c), (e), (l).

[38] Supra note 33.

[39] Supra note 5, at 221.

[40] It is “potential” since the Space Protocol has not yet entered into force and may not receive a general acceptance in the near future; it is “potential” also due to the fact that the Space Protocol has already excluded most of Aircraft Objects in general.

[41] The Outer Space Treaty Art. X provides that “[i]n order to promote international cooperation in the exploration and use of outer space, […] the States Parties to the Treaty shall consider on a basis of equality any requests by other States Parties to the Treaty to be afforded an opportunity to observe the flight of space objects launched by those States. […]”

[42] See the Rescue Agreement Art. 5.

[43] See the Liability Convention Arts. 1(c), (d); the Registration Convention Arts. 1(a), (b).

[44] See the Moon Agreement Arts. 3(2), 13.

[45] For instance, the term Space Object can be found in the Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space, adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 47/68 of 14 December 1992; the Resolution 59/115 of 10 December 2004 – Application of the concept of the “launching State”; the Resolution 62/101 of 17 December 2007 – Recommendations on enhancing the practice of States and international intergovernmental organizations in registering space objects, etc.

[46] See the Space Protocol Art. XXXV.

[47] The Moon Agreement Art. 3(2) provides that “[…] it is likewise prohibited to use the Moon in order to commit any such act or to engage in any such threat in relation to the Earth, the Moon, spacecraft, the personnel of spacecraft or manmade space objects.” What is the relationship between the “spacecraft” and the “manmade space objects” in this article is also not clear.

[48] See supra note 19, at 27.

[49] See SIA, Statement of the Satellite Industry Association on the Revised Preliminary Draft Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (18 October 2010), (www.esoa.net/upload/files/news/unidroit/20101018sia.pdf), last visited (12.04.2014).

[50] See supra note 19, at 27.