“Space Asset” Under the Space Protocol to the Cape Town Convention and the Related Issues Under International Space Law

By Pai Zheng & Ruo Wang

Pai Zheng is an Assistant Professor at the International Law School of East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPL), Shanghai, China. He holds an LL.M. (Air and Space Law) from Leiden University, the Netherlands, an LL.M. (Public International Law) and a Ph.D. in Law (Cum Laude) from ECUPL.

Ruo Wang is an LL.M. Candidate (Public International Law) at the International Law School of East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPL), Shanghai, China.

Table of Contents

1. Abstract

The ongoing privatization and commercialization of today’s space industry creates more financial risks for private sector financiers, and the movable nature of space activities may cause legal uncertainties of the security interests. Given such situation, the 2001 UNIDROIT Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (the “Cape Town Convention”) and the 2012 Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on Matters Specific to Space Assets (the “Space Protocol”) marked a significant development in harmonizing and unifying the rules of asset-backed finance for mobile space equipment. As a key term in the Space Protocol, the concept of “Space Asset” was for the first time introduced in the Cape Town Convention and defined under the Space Protocol, which may impact contemporary international space law that formed mainly from the UN space law treaties (the “five United Nations treaties on outer space”) and principles (the “five United Nations declarations and legal principles”). This article will first explain and analyze the definition of “Space Asset”, then further discuss issues related to this new concept, including the delimitation of outer space, the relationship between an Aircraft Object and a Space Asset, as well as the differences and similarities between Space Assets under the Space Protocol and a Space Object under the UN space law treaties.

2. Introduction

Due to the increasing privatization and commercialization of space activities, the development of the space industry requires huge investments, and except for governmental investment, today, more and more space equipment is financed by private entities such as banks, investment companies, insurance companies and other financial institutions. For instance, early in 2008, SpaceX, a U.S. privately-held aerospace manufacturer and space transport services provider, collected a USD 20 million equity investment from Founders Fund, a venture capital firm managed by the co-founders of PayPal, and in 2017, SpaceX increased the size of its latest funding round by USD 100 million to USD 450 million.[1] Nowadays, a fully operational reusable launch system (RLS) or reusable launch vehicle (RLV)[2] with modern technology may cost USD 10 billion.[3] These ongoing developments in the space industry create more financial risks for private sector financiers. The financiers have a lower probability of being repaid than before, since their investment risk is no longer assumed by States or the governments. Therefore, these investment activities, especially for the asset-based financings, need to be protected and stabilized under law.

However, mobile equipment of high value or a particular economic significance such as a satellite is highly movable by its very nature, and it may keep crossing national borders or operate outside sovereign territory during its lifetime. This movable nature may cause legal uncertainties when a security interest is created on a cross-border space equipment through asset-based financing, as which domestic law shall apply to regulate the security interest is questionable. Therefore, the concern is raised at an international level, in so far as there is no clear answer for whether the security interest created under the domestic laws of State A is still valid and enforceable in State B or other States. Given such situation, the UNIDROIT Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (the “Cape Town Convention”)[4] adopted in 2001, together with the Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on Matters Specific to Space Assets (the “Space Protocol”)[5] adopted in 2012, marked a significant step forward in harmonizing and unifying the rules of national laws on the subject of asset-backed finance for mobile space equipment.[6] Prior to the adoption of the Space Protocol, the validity of security interests depended on several different factors, such as national laws of different States, or bilateral arrangements between certain States.[7]

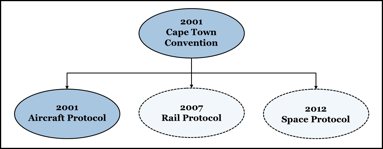

The whole Cape Town Convention regime, as illustrated in Figure I with the documents in force marked in blue-grey, is structured as a main convention, i.e., the Cape Town Convention itself, with four separate protocols that deal with four kinds of different movable equipment assets: the 2001 “Aircraft Protocol” on matters specific to “Aircraft Equipment,”[8] the 2007 “Rail Protocol” on matters specific to “Railway Rolling Stock,”[9] the 2012 “Space Protocol” on matters specific to “Space Assets,” and the 2019 “MAC Protocol” on matters specific to “Mining, Agricultural and Construction Equipment”.[10] Under the Cape Town Convention regime, each specified protocol shall be read and interpreted together with the convention as a whole; for instance, the Space Protocol and the Cape Town Convention shall be known as the “Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment as [A]pplied to [S]pace [A]ssets.”[11] In addition, in case that there is any inconsistency between the Cape Town Convention and the protocols, the protocols shall prevail.[12] Up to now, only the Cape Town Convention (with 83 States Parties and the EU as a regional economic integration organization) and the Aircraft Protocol (with 80 States Parties and the EU)[13] have entered into force, and there are only four States that have signed the Space Protocol, namely Burkina Faso, Germany, Saudi Arabia and Zimbabwe.[14]

Figure I

This article mainly focuses on the concept of “Space Asset”, which was introduced for the first time in the Cape Town Convention and defined under the Space Protocol, as well as the potential impact of this new concept on existing international space law that formed mainly from the UN space law treaties back in the 1960s and 1970s.[15] The next section of this article will explain and analyze the definition of Space Asset in the context of international law, and the third section will further discuss issues related to Space Assets, including whether the question on the definition and delimitation of outer space will affect the identification of a Space Asset, the relationship between a Space Asset and an Aircraft Object under the Cape Town Convention regime, and the relationship between a Space Asset under the Space Protocol and a Space Object under UN space law treaties. The last section will conclude the study and provide certain comments.

3. Description of Space Asset Under the Space Protocol

3.1. Definition of Space Asset

The concept of Space Asset appears for the first time in Article 2(3)(c) of the Cape Town Convention without a definition, and it is the Space Protocol that provides the full definition of Space Asset.[16] Pursuant to Article 1(2)(k) of the Space Protocol, the Space Asset is defined as any man-made uniquely identifiable asset in space or designed to be launched into space, and comprising:

- a spacecraft, such as a satellite, space station, space module, space capsule, space vehicle, or reusable launch vehicle (RLV), whether or not including a space asset falling within (b) or (c) below;

- a payload (whether telecommunication, navigation, observation, scientific or otherwise) in respect to which a separate registration may be affected in accordance with the regulations; or

- a part of a spacecraft or payload such as a transponder, in respect to which a separate registration may be affected in accordance with the regulations, together with all installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto.[17]

The term “Space” in “Space Asset” refers to “outer space” including the moon and other celestial bodies, which is consistent with UN space law treaties.[18] Also, the Space Protocol shall not apply to Aircraft Objects under the Aircraft Protocol, except where such objects are primarily designed for use in outer space, regardless of whether its actual position is in outer space or not.[19] Moreover, the Space Protocol shall not apply to an Aircraft Object merely because it is designed to be temporarily operating in outer space.[20] Although these provisions are aiming to avoid potential overlaps and contradictions between the Space Protocol and the Aircraft Protocol, as to objects or equipment that fall within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol and at the same time meet the condition of “primarily designed for use in [outer] space” under the Space Protocol, there remains a degree of uncertainty, which will be discussed in Section 3.2 below.

3.2. Analysis of the Definition

Pursuant to the definition and description of Space Asset, there are certain requirements that must be fulfilled for space equipment or objects to be qualified as Space Assets under the Cape Town Convention regime.[21] The required criteria are explained as follows:[22]

First, the object or equipment must be man-made. For instance, minerals or asteroids from the moon or other celestial bodies are unlikely to be treated as Space Assets per se under the Space Protocol, even if they are high-valued. However, if the natural resource from space is transformed through human activities into new form, material, or object, the transformed object can be seen as a Space Asset according to the Protocol.[23]

Second, the object or equipment must be uniquely identifiable under the Cape Town Convention regime. The Convention states that for a security interest that constituted an international interest, the related agreement shall enable an asset or object identified in conformity with each Protocol to the Convention.[24] In fact, the Space Protocol provides that a description of a Space Asset is sufficient for identification if it contains one or more of the following elements:

- a description of the Space Asset by item;

- a description of the Space Asset by type;

- a statement that the agreement covers all present and future Space Assets;[25] or

- a statement that the agreement covers all present and future Space Assets except for specified items or types.[26]

As explained in a 2010 UNIDROIT Secretariat Report, the identification criteria for Space Assets are for registration purposes;[27] however, these descriptions for identification requirements provided by the Space Protocol are rather vague, generic and open-ended, especially in comparison with the Aircraft Protocol. The latter requires more specific technical descriptions such as the manufacturer’s serial number, name of manufacturer and model designation.[28] One possible reason for this is that the drafters of the Space Protocol did not intend to add burdens and duties for private entities to increase costs and add confusion to an already expensive and complicated activity.[29] That said, the vagueness of the identifiable requirement for the Space Asset may cause practical problems in relation to the international registration system.

Third, the object or equipment must be

- in outer space; or

- designed to be launched into outer space.

This means that the Space Protocol adopted both the spatialism approach, i.e., the object is literally located “in” outer space, and the functionalism approach, i.e., the purpose or aim for the object is “space oriented” regardless of the object’s actual physical location, which indeed has broadened the scope of the Space Asset and may better serve financiers’ interest. Thanks to the functionalism approach, the Space Asset covers not only an object or equipment already located in outer space, but also an object or equipment that has not yet been launched, such as an object being manufactured, in storage, en route for launching, or on the launch pad, etc., if the object or equipment has been designed to be launched into outer space.[30]

Fourth, the object or equipment must be

- a spacecraft, whether or not including a separate registered Space Asset;

- a payload which is separately registered; or

- a part of a spacecraft or payload, together with “attachments” which include:

- all installed, incorporated or attached accessories; and

- parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto.

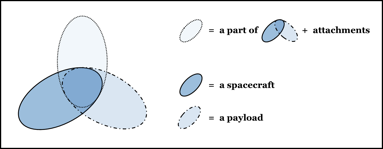

The illustrated examples in the Space Protocol, such as a reusable launch vehicle like the SpaceX Falcon 9 or a navigational satellite as payload,[31] are not exhaustive. However, it is supposed that these Space Assets are high-valued ones. It is worth mentioning that Space Asset also covers all the “attachments” related to the spacecraft or payload as widely as possible, even including data, manuals and records. It should also be noted that under the protocol, these data, manuals and records are separately registrable,[32] which means that it is possible for the designing records of a satellite to be treated as Space Assets even if the satellite has not been made or is not able to be made in the future, as long as the unmade satellite is designed to be launched into outer space. Besides, the payload and spacecraft may have certain overlapping areas; for example, a navigational satellite can be deemed to be both a spacecraft and the payload of a rocket on which it was launched.[33] The relationship between the aforementioned items is illustrated as follows in Figure II.

Figure II

Fifth, to be a Space Asset, the object, equipment, or related part must be separately registrable according to the regulations governing the registration of international interests in Space Assets.[34] This registration requirement is different from the State obligation under the 1975 Registration Convention since here, it is the private financiers’ security interests created on the Space Assets that are under concern. A supervisory authority pursuant to the Protocol shall create an international registry system.[35]

4. Issues Related to Space Asset Under International Space Law

4.1. The Issue Related to Delimitation of Outer Space

The question on the definition and delimitation of outer space and airspace is relevant here because in defining the term Space Asset, the Space Protocol mentioned the condition that the object or equipment must be “[physically located] in [outer] space.”[36] It seems that there is no problem for an on-orbit satellite or an object in orbit or beyond orbit to fall within this category. However, without a definitive answer to the question on the delimitation of outer space, i.e., where outer space begins, it is not clear whether an object or equipment can be qualified as a Space Asset when it is physically located below an altitude of 100 kilometers, i.e., the Kármán line, in an altitude of 100 kilometers, in sub-orbital area which may reach 105 kilometers, etc.[37]

Neither the UN space law treaties nor any other international treaties related to air and space law defines the upper borders of airspace, and for now, although partial consensus appears to exist on delimitation between 80 and 120 kilometers above the surface of the Earth, it has not yet been widely accepted by the international community.[38] That said, this problem as related to identifying a Space Asset may not be as serious as it appears, insofar as the Space Protocol has also provided a parallel category of the object or equipment “designed to be launched into [outer] space”. Although one may argue that here “into [outer] space” still involves the delimitation issue and needs clarification anyway, what is important in this phrase is “designed to be…”, which provides an opportunity to bypass the unsettled delimitation issue that may be unsettled for a long time.

The “designed to be…” can be interpreted as a functionalism approach for defining Space Asset, i.e., if the aim, objective, or purpose of an object or equipment is designed as space-oriented and not as aircraft-oriented, the object or equipment is qualified to be a Space Asset, provided that all the other requirements under the Space Protocol are fulfilled. It is quite clear that “designed to be launched into [outer] space” does not require the object or equipment to be actually “located in” or “launched into” outer space, regardless of how we define “[outer] space.” Furthermore, this approach even allows the attachments of an object or equipment to be qualified as a Space Asset without manufacturing or launching the relevant object. In sum, the conclusions on this issue are as follows:

- it is difficult to define a Space Asset only based on the phrase “[physically located] in [outer] space” under Article 1(2)(k) of the Space Protocol, since there is no internationally recognized definition of “space” or “outer space,” and the Protocol does not provide a definition within the Cape Town Convention regime; however,

- the problem can be solved by reference to the Space Protocol itself since Article 1(2)(k) of the protocol also provides an alternative approach by defining Space Asset by its function, which can circumvent the impasse of the delimitation debate.

4.2. Space Asset v. Aircraft Object

As mentioned before, the Space Protocol will not apply to an object or equipment falling within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol, and it will not apply to an Aircraft Object that is designed to be temporarily in outer space. The only exception is an Aircraft Object which is “primarily designed for use in [outer] space” and thus can be treated as a Space Asset de facto.[39] Thus, potential overlapping is possible on the condition that an object or equipment falls within the definition of Aircraft Object under the Aircraft Protocol while at the same time meets the condition of “primarily designed for use in [outer] space” under the Space Protocol. Besides, this issue discussed is theoretical mainly because the Space Protocol has not entered into force.

Before going into details, it is worth pointing out that the question of a specific object or equipment, such as a sub-orbital “spacecraft” like the Virgin Galactic SS2, is deemed to be a Space Asset, an Aircraft Object, or both, to some extent, is different from the general question of which law, i.e., international air law or international space law, will apply to “activities” that involve both international air law and international space law, such as a sub-orbital “flight and operation.”

The former is a specific question about determining the proper applicable rules for an object or equipment functioning as an asset under and only under the Cape Town Convention regime, which has its main concerns about asset finance. That is to say, the concepts of Space Assets and Aircraft Objects only function within the Cape Town Convention regime and the context of financial transactions.

The latter question, by contrast, is a generic question about the delimitation issue, as aforementioned, and establishing proper boundaries for international air law and international space law in general. This is not to say that there is no connection or similarity between the two questions, as both questions are similar insofar as they both involve international air law and space law, spatialism approaches and functionalism approaches, as well as some overlapping categories.

In sum, the two questions are different in the sense that the former is mainly focusing on the objects or equipment as assets and, as the difference between air law and space law is not the main focus of the Cape Town Convention, here, the necessity of dealing with this “air law or space law” issue related to objects or equipment of particular economic significance, is rooted in the specific context of commercial and financial practice.

It should be noted that the Space Protocol does not state that an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in outer space “is” a Space Asset; it only provides that in that case, the Space Protocol “will apply” to that Aircraft Object.[40] Thus the related object retains its legal status as an Aircraft Object defined under the Aircraft Protocol, while at the same time it is treated as a Space Asset de facto. Therefore, the issue here is not really about the differentiation between an Aircraft Object and a Space Asset, but rather a question of what the conditions for the Space Protocol are to apply to an Aircraft Object.

Under the Aircraft Protocol, an Aircraft Object is referred to as airframe, aircraft engine and helicopter,[41] and the “airframe”[42] and “aircraft engine”[43] are separately defined in detail, which is quite clear and reasonably practicable. In short, objects or equipment is qualified as an Aircraft Object if:

- it is certified by the competent aviation authority to transport;

- it has jet propulsion, turbine-powered, or piston-powered engine; and

- it has a capacity for at least eight persons (five persons for helicopters) including crew or goods more than 2,750 kilograms (450 kilograms for helicopters).[44]

Here, the problem is not about defining an Aircraft Object, but how to decide the conditions listed in Article 2 of the Space Protocol.[45] If objects or equipment are qualified as an Aircraft Object, the Space Protocol is generally excluded; however, there are two situations that need to be examined for the applicability of the Space Protocol to an Aircraft Object:

- the Space Protocol applies to an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in outer space, even such object is not located in outer space. This condition is a functionalism-approach since the physical position of the object is irrelevant, which is consistent with the second category of the Space Asset as aforementioned. What is not clear is that the term “primarily” is quite vague and lacks a shared understanding or interpretation. The phrase “designed ‘for use’ in [outer] space” already shows the objective and purpose of the object is a key element, while the meaning of the term “use” is not that clear either; and

- the Space Protocol does not apply to an Aircraft Object which is designed to be temporarily in outer space. There is a slight difference in this condition as compared to the above illustration, as the phrase here is “designed ‘to be temporarily in’ [outer] space” instead of “designed ‘for use’ in [outer] space” as abovementioned. This means that an Aircraft Object which is merely designed to stay for a “short time” in outer space and not for use in outer space will be excluded from the Space Protocol. Although the meaning of “temporarily” is undefined, one may argue that an object which is designed to transit from airspace to outer space should be excluded.[46]

In sum, the conclusions on this issue are that:

- in general an Aircraft Object is not governed by the Space Protocol even if it is designed to be temporarily in outer space;

- potential overlapping of the Aircraft Protocol and Space Protocol is possible on condition that an object or equipment both falling within the category of Aircraft Object as defined under the Aircraft Protocol and the category of “primarily designed for use in [outer] space” as prescribed in the Space Protocol;[47] and

- the undefined terms of “primarily”, “use” and “temporarily” are unclear in Article 2 of the Space Protocol. Given such situation, an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in outer space can be governed by the Space Protocol as if it is a Space Asset de facto, regardless of its actual physical location.

4.3. Space Asset v. Space Object

The new term of Space Asset defined under the Space Protocol is different from the term Space Object, which has been used in several UN space law treaties since the creation of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. However, for now there is no definition of Space Object and its meaning is still unclear.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty mentions Space Object only in Article 10 without further explanation, which provides that “[i]n order to promote international cooperation in the exploration and use of outer space, […] the States Parties to the Treaty shall consider on a basis of equality any requests by other States Parties to the Treaty to be afforded an opportunity to observe the flight of [S]pace [O]bjects launched by those States.”[48] Similarly, the 1968 Rescue Agreement only mentions “a [S]pace [O]bject or its component parts” or ”objects launched into outer space or their component parts.”[49] The 1972 Liability Convention and the 1975 Registration Convention both mention “the launching of a [S]pace [O]bject” and explain that the term Space Object “includes component parts of a [S]pace [O]bject as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof,”[50] and the 1979 Moon Agreement mentions “in relation to the Earth, the Moon, spacecraft, the personnel of spacecraft or man-made [S]pace [O]bjects” and “a [S]pace [O]bject, or its component parts.”[51] The other UN space law instruments also used the term Space Object without defining it.[52] As for a Space Asset, it is clearly defined in the Space Protocol as explained in the first section.

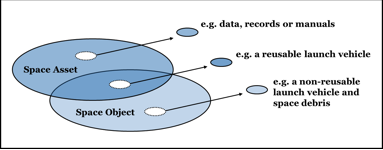

Pursuant to the Space Protocol, provisions of the protocol, together with the Cape Town Convention, do not affect the existing UN space law treaties or instruments of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU),[53] which means that whether objects or equipment qualify as both a Space Asset and a Space Object, the applicable UN treaty rules prevail.[54] But this only explains the relationship between the rules of the Space Protocol and UN space law treaties, not the relationship between the two terms or concepts. In fact, at this moment there is no clear answer to this question and indeed, the relationship between a Space Asset and a Space Object is quite complicated. That said, this article will try to draw certain preliminary conclusions based on the ideas which back up these two concepts, i.e., the motive, aim, objective and purpose behind the two terms. In this sense, there are at least three main differences between the two terms or concepts, and the general relationship between the two terms is illustrated in Figure III below.

Figure III

A Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention regime is private and commercial law-oriented, particularly focusing on asset-based finance,[55] while a Space Object under the UN space law treaties is public international law-oriented. The purpose or motive for creating the concept of Space Asset is rooted in the practical need for asset-based financing of the mobile space equipment; thus, the concept is linking up with private financiers as creditors, which is mainly focused on the protections of the financiers’ private security interest.[56] On the other hand, the undefined term Space Object is linked to sovereign States and their international obligation, responsibility, and liability. The term Space Object has been widely used in the 1968 Rescue Agreement,[57] the 1972 Liability Convention,[58] and the 1975 Registration Convention,[59] all of which clearly have State responsibility and liability concerns.

A Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention regime is high-value oriented since by definition it is an asset, while a Space Object within the meaning of the UN space law treaties does not have such concerns. This allows us to separate certain objects that are not high-valued or without particular economic significance out of the scope of Space Assets: for instance, a non-reusable launch vehicle and space debris are not qualified as Space Assets, but both of them can be Space Objects. Moreover, certain kind of attachments such as dates, records, or manuals of the related space equipment are qualified as Space Assets, insofar as they have high values for the financiers. However, these attachments on Earth are hardly to be treated as Space Objects.

The Space Asset under the Cape Town Convention adopted both the spatialism and the functionalism approaches in defining the term, while for Space Object it is more likely that the spatialism approach prevails. The Space Protocol clearly states that a Space Asset can be located in outer space or designed to be launched into outer space. In the latter case, there is no need for the asset to be physically “located in” or “launched into” outer space, however “outer space” is defined. Therefore, the physical position of a Space Asset is not that important, and it can be in outer space, en route to outer space, or on Earth. As for a Space Object, the position of the object clearly matters, although there is no clearance on this issue. This is because in several circumstances, the 1968 Rescue Agreement,[60] the 1972 Liability Convention,[61] and the 1975 Registration Convention have used the term Space Object under a potential background that the object related is literally located in outer space.[62]

Except for the differences, there are also some shared features of the two terms, which can be listed as follows:

Both of them are involved with human efforts, i.e., man-made, although the wording in 1979 Moon Agreement seems to imply the existence of certain non-manmade Space Objects, as it prescribes that “[i]t is likewise prohibited to use the Moon in order to commit any such act or to engage in any such threat in relation to the Earth, the Moon, spacecraft, the personnel of spacecraft or man-made [S]pace [O]bjects.”[63] What is also not clear is the relationship between “spacecraft” and “man-made Space Objects” in this article.

Both include component parts as well as the launch vehicle and parts thereof. For a Space Asset, it covers component parts of the “spacecraft or payload”, and for a Space Object, it covers component parts of the “Space Object” and component parts of the “launch vehicle”.

There are overlapping areas for the two terms; for instance, a reusable launch vehicle such as the SpaceX Falcon 9 is a Space Asset under the Space Protocol, and at the same time it is also a Space Object under the UN space law treaties.

A simplified comparison between the Space Asset and the Space Object is illustrated in Figure IV.

| Term | Space Asset | Space Object |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation | private & commercial law | public international law |

| Value | high-valued | n/a |

| Approach | spatialism & functionalism | can be spatialism |

| Human Involvement | man-made | man-made |

| Coverage | spacecraft & payload | space object & launch vehicle |

| component parts | component parts | |

| attachments | n/a |

Figure IV

5. Conclusions and Comments

As the first international space law treaty created for unifying private law related to space equipment financing, the Space Protocol to the Cape Town Convention marked a significant step forward in harmonizing the rules of domestic private laws about asset-backed finance for mobile space equipment. However, so far, it is not welcomed by most States or the space industry, and is unlikely to enter into force in the near future.[64] The Protocol was especially opposed by space industry organizations such as the Satellite Industry Association (SIA).[65] The general opinion of the industry is that the existing models and practice of asset-backed finance for space equipment are sufficient and that the protocol has added an unnecessary supra-national layer of law to the financing industry.[66] As for the concept of Space Asset under the protocol, one particular concern is that the definition and description of Space Asset is too vague;[67] yet at the same time, it broadens the sphere of “asset” and allows for the development of new kinds of assets which could usefully be the subject of an international interest under the Cape Town Convention regime.[68] And in addition, the protocol may create opportunities for the private law-oriented concept of Space Asset to interact with the existing public law-oriented UN space law treaties, which could be a real challenge within the context of ongoing privatization and commercialization of space industry.[69]

Given such situation, this article holds the position that the adoption of the Space Protocol provided potential impacts on the financing industry as well as international space law, insofar as it created new legal terms and descriptions for contemporary space activities. Despite its shortcomings such as vague wording, missing definitions of certain terms and overelaborated rules and regulations, the concept of Space Asset introduced in the Cape Town Convention and defined under the Space Protocol was a huge development in contemporary international space law.

Certain comments related to this study can be listed as follows:

It is difficult to define the Space Asset based on the phrase “in [outer] space” under Article 1(2)(k) of the Space Protocol, since the debate of delimitation of outer space has not been resolved at an international level; however, the problem can be solved pursuant to the same article of the Space Protocol since it adopted both the spatialism and the functionalism approaches in defining the term, which may circumvent the impasse of the delimitation issue.

In general, an Aircraft Object defined under the Aircraft Protocol is not governed by the Space Protocol even if it is designed to temporarily stay in outer space; however, given the fact that the words of “primarily”, “use” and “temporarily” are not precise enough, an Aircraft Object which is primarily designed for use in outer space can be governed by the Space Protocol as if it is a Space Asset de facto, regardless of its actual physical location.

The main difference between a Space Asset and a Space Object is that the former is private and commercial law-oriented, high-value oriented, and is mainly linked to private financial entities and their private interests, while the latter is public law-oriented and mainly connected with State obligations, responsibilities, and liabilities under public international law. There are also similarities and overlapping areas between the two concepts. When an object or equipment qualifies as both a Space Asset and a Space Object, the applicable UN space treaty rules shall prevail.

[1] See Spacewatch.Global, SpaceX Aims to Raise US $1.7 Billion in Funding Round (23 May 2022), last visited (12.10.2022); B. Berger, PayPal Co-Founders Invest $20 Million in SpaceX (5 August 2008), last visited (12.10.2022); J. Foust, SpaceX Adds $100 Million to Latest Funding Round (28 November 2017), last visited (12.10.2022).

[2] For more information about reusable launch vehicle (RLV) and its latest development, see, e.g., H. Kuczera and P.W. Sacher, Reusable Space Transportation Systems 1-32 (Springer, 2011); Orbital Today, Reusable Launch Vehicles Today & Tomorrow (28 Mar 2022), last visited (12.10.2022).

[3] M. van Pelt, Space Tourism: Adventures in Earth Orbit and Beyond 112 (Copernicus Books, 2005).

[4] Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (hereinafter the “Cape Town Convention“), signed at Cape Town on 16 November 2001.

[5] Protocol to the Convention on International Interest in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (hereinafter the “Space Protocol“), signed in Berlin on 9 March 2012.

[6] The Cape Town Convention entered into force on 1 March 2006, and for now there are 83 Contracting States and one Regional Economic Integration Organization, i.e., the EU, as a Contracting Party; see UNIDROIT, Status – Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town, 2001), (https://www.unidroit.org/status-2001capetown), last visited (12.10.2022); The Space Protocol has not yet entered into force; see UNIDROIT, Status – UNIDROIT Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (Berlin, 2012), (http://www.unidroit.org/status-2012-space), last visited (12.10.2022).

[7] See L. Ametova, International Interest in Space Assets Under the Cape Town Convention, 92 Acta Astronautica 213, 213-14 (2013).

[8] Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment (hereinafter the “Aircraft Protocol“), signed at Cape Town on 16 November 2001.

[9] Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Railway Rolling Stock (hereinafter the “Rail Protocol“), signed in Luxembourg on 23 February 2007.

[10] Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment specific to Mining, Agriculture and Construction Equipment (hereinafter the “MAC Protocol“), signed in Pretoria on 22 November 2019.

[11] See the Space Protocol Art. 2(2).

[12] See the Cape Town Convention Art. 6.

[13] See UNIDROIT, Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town, 2001) – States Parties, https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/cape-town-convention/states-parties), last visited (12.10.2022); and UNIDROIT, Declarations Lodged by the European Union Under the Aircraft Protocol at the Time of the Deposit of Its Instrument of Accession, (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/aircraft-protocol/states-parties), last visited (12.10.2022).

[14] See UNIDROIT, Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment – States Parties, (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/aircraft-protocol/states-parties), last visited (12.10.2022); UNIDROIT, States Parties – Luxembourg Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Railway Rolling Stock (Luxembourg, 2007), (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/rail-protocol/status), last visited (12.10.2022); UNIDROIT, Mac Protocol – States Parties, (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/mac-protocol/status), last visited (12.10.2022); and UNIDROIT, Status – Unidroit Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (Berlin, 2012), (https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/security-interests/space-protocol/status), last visited (12.10.2022).

[15] There are five core UN space law treaties, namely (a) Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Outer Space Treaty“), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2222 (XXI), opened for signature on 27 January 1967, entered into force on 10 October 1967; (b) Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Rescue Agreement“), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2345 (XXII), opened for signature on 22 April 1968, entered into force on 3 December 1968; (c) Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the “Liability Convention“), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 2777 (XXVI), opened for signature on 29 March 1972, entered into force on 1 September 1972; (d) Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Registration Convention“), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 3235 (XXIX), opened for signature on 14 January 1975, entered into force on 15 September 1976; and (e) Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Moon Agreement“), adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 34/68, opened for signature on 18 December 1979, entered into force on 11 July 1984; in general, see UNOOSA, International Space Law: United Nations Instruments (ST/SPACE/61/Rev.2), (http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/stspace/stspace61rev.2_0.html), last visited (12.10.2022).

[16] The Cape Town Convention simply mentioned that an international interest in mobile equipment is an interest in a uniquely identifiable object of a category of such objects as (a) airframes, aircraft engines and helicopters; (b) railway rolling stock; and (c) Space Assets. See the Cape Town Convention Art. 2.

[17] The Space Protocol Art. 1(2)(k).

[18] The Space Protocol Art. 1(2)(j); see also Outer Space Treaty Arts. 1, 2.

[19] The Space Protocol Art. 2(3); see also infra note 41.

[20] The Space Protocol Art. 2(4); see also infra note 41.

[21] For a discussion of the early evolution of the term Space Asset in the Cape Town Convention, see, e.g., S. Ospina, The Concepts of Assets and Property: Similarities and Differences, and Their Applicability to Undertakings in Outer Space, Proceedings of the Forty-Fifth Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (2003), vol. 12; O.M. Ribbelink, The Protocol on Matters Specific to Space Assets, 12 European Review of Private Law 37, 39 (2004); and Y. Zhao, Revisiting Selected Issues in the Draft Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on Matters Specific to Space Assets, 76 Journal of Air Law and Commerce 805, 814-15 (2011); see also UNIDROIT, Study LXXII J – Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (2000-2011), (https://www.unidroit.org/studies/security-interests/#1622928573561-5609f8e6-eb57), last visited (12.10.2022).

[22] For the conditions and requirements of Space Asset, see also C. Xia, On the Definition of Space Assets (in Chinese), 13(1) Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Science Edition) 79, 79-83 (2011).

[23] M.J. Sundahl, The Cape Town Convention: Its Application to Space Assets and Relation to the Law of Outer Space 35 (Martinus Nijhoff, 2013).

[24] The “agreement” here should be referred to as (a) a security agreement, (b) a title reservation agreement or (c) a leasing agreement; see the Cape Town Convention Art. 1(a). The Cape Town Convention Art. 7(c); also the Space Protocol Article 5 states that a contract of sale is one which “(c) enables the [S]pace [A]sset to be identified in conformity with this Protocol”; and the Space Protocol Article 9 states that “[a] transfer of debtor’s rights is constituted as a rights assignment where it is in writing and enables: (a) the debtor’s rights the subject of the rights assignment to be identified; (b) the [S]pace [A]sset to which those rights relate to be identified.”

[25] Supra note 24.

[26] The Space Protocol Art. 7(1); also the Space Protocol Article 7(2) states that “an interest in a future [S]pace [A]sset identified in accordance with Article 7(1) shall be constituted as an international interest, as soon as the chargor, conditional seller or lessor acquires the power to dispose of the [S]pace [A]sset, without the need for any new act of transfer.”

[27] See UNIDROIT Secretariat, Intersessional Consultations with Representatives of the International Commercial Space and Financial Communities (Rome, 18 Oct 2010): Report, C.G.E./Space Pr./5/W.P.4, at 6.

[28] See the Aircraft Protocol Art. 7.

[29] Supra note 28, at 6-7.

[30] Supra note 23, at 35.

[31] See SpaceX, Falcon 9, (www.spacex.com/falcon9), last visited (12.10.2022).

[32] See the Cape Town Convention Arts. 16, 17; the Space Protocol Art. 28; see also the Space Protocol Chapter 3 – Registry Provisions Relating to International Interests in Space Assets, which provides the details for creating an international registration system.

[33] Supra note 23, at 37.

[34] Ibid., at 50-51; see also supra note34.

[35] Supra note 33.

[36] For more information about the delimitation issue, see, e.g., UN COPUOS, Promoting the Discussion of the Matters Relating to the Definition and Delimitation of Outer Space with a View to Elaborating a Common Position of States Members of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, 13 June 2017, A/AC.105/C.2/L.302, (http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/aac.105c.2l/aac.105c.2l.302_0.html), last visited (12.10.2022); UN COPUOS, The Challenging Context of Considering Complete Aspects of Delimitation of Airspace and Outer Space: Arguments for Adding Dialectical Elements to, and Setting Newer Analytical Trends in, Discussing the Issue, 16 June 2017, A/AC.105/2017/CRP.7, (https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/aac_1052017crp/aac_1052017crp_7_0_html/AC105_2017CRP07ER.pdf), last visited (12.10.2022); UN COPUOS, Report of the Chair of the Working Group on the Definition and Delimitation of Outer Space, 14 April 2017, A/AC.105/C.2/2017/DEF/L.1, (http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/aac.105c.2def/aac.105c.22017defl.1_0.html), last visited (12.10.2022); UN COPUOS, Matters Relating to the Definition and Delimitation of Outer Space: Replies of the International Institute of Space Law (IISL), 4 April 2017, A/AC.105/C.2/2017/CRP.29, (http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/aac.105c.22017crp/aac.105c.22017crp.29_0.html), last visited (12.10.2022); ECSL, Delimitation of Outer Space, (http://www.esa.int/About_Us/ECSL_European_Centre_for_Space_Law/Delimitation_of_Outer_Space#Other%20documents), last visited (12.10.2022).

[37] For the discussion on this issue, see also L. Ametova, International Interest in Space Assets Under the Cape Town Convention, 92 Acta Astronautica 213, 223, 225 (2013) and M.J. Sunahl, The Cape Town Convention: Its Application to Space Assets and Relation to the Law of Outer Space 36, 134-41 (Martinus Nijhoff, 2013).

[38] See P. Mendes de Leon, Introduction to Air Law (Tenth Edition) 22 (Kluwer Law International, 2017).

[39] Supra notes 19, 20.

[40] The Space Protocol Article 2 — Application of the Convention as regards space assets, debtor’s rights and aircraft objects — states that ” (1) The Convention shall apply in relation to [S]pace [A]ssets, rights assignments and rights reassignments as provided by the terms of this Protocol. […] (3) This Protocol does not apply to objects falling within the definition of [A]ircraft [O]bjects under the Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters specific to Aircraft Equipment except where such objects are primarily designed for use in [outer] space, in which case this Protocol applies even while such objects are not in [outer] space. (4) This Protocol does not apply to an [A]ircraft [O]bjects merely because it is designed to be temporarily in [outer] space [emphasis added].”

[41] The Aircraft Protocol Art. 1(2)(c).

[42] Airframes means airframes (other than those used in military, customs or police services) that, when appropriate aircraft engines are installed thereon, are type certified by the competent aviation authority to transport: (i) at least eight (8) persons including crew; or (ii) goods in excess of 2,750 kilograms, together with all installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment (other than aircraft engines), and all data, manuals and records relating thereto. See the Aircraft Protocol Art. 1(2)(e).

[43] Aircraft engines means aircraft engines (other than those used in military, customs or police services) powered by jet propulsion or turbine or piston technology and:

(i) in the case of jet propulsion aircraft engines, have at least 1,750 lb of thrust or its equivalent; and

(ii) in the case of turbine-powered or piston-powered aircraft engines, have at least 550 rated take-off shaft horsepower or its equivalent, together with all modules and other installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto. See the Aircraft Protocol Art. 1(2)(b).

[44] The Aircraft Protocol Art. 1(2)(a), (b), (c), (e), (l).

[45] Supra note 41.

[46] Supra note 7, at 221.

[47] It is “potential” since the Space Protocol has not yet entered into force and is unlikely to receive a general acceptance in the near future; it is “potential” also due to the fact that the Space Protocol has already excluded most of Aircraft Objects in general.

[48] See the Outer Space Treaty Art. 10.

[49] See the Rescue Agreement Art. 5.

[50] See the Liability Convention Art. 1(c), (d); the Registration Convention Art. 1(a), (b).

[51] See the Moon Agreement Arts. 3(2), 13.

[52] For instance, the term Space Object can be found in the Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space, adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 47/68 of 14 December 1992; the Resolution 59/115 of 10 December 2004 – Application of the concept of the “launching State”; the Resolution 62/101 of 17 December 2007 – Recommendations on enhancing the practice of States and international intergovernmental organizations in registering space objects, etc.

[53] For more information about the ITU Instruments, see ITU, ITU Publications, (https://www.itu.int/en/publications/Pages/default.aspx), last visited (12.10.2022).

[54] See the Space Protocol Art. 35.

[55] That said, there are also public features in the Space Protocol and the Cape Town Convention, such as the international registry system created under the Cape Town Convention, the declaration system related to State obligation and the jurisdiction provisions, etc. See L. Weber, Public and Private Features of the Cape Town Convention, 4 Cape Town Convention Journal 53, 54-60 (2015).

[56] See M.J. Sundahl, The Cape Town Convention and the Law of Outer Space: Five Scenarios, 3 Cape Town Convention Journal 109, 109-12 (2014); see also P.B. Larsen, Critical Issues in the UNIDROIT Draft Space Protocol, Proceedings of the Forty-Fifth Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics) 2, 4 (2003).

[57] For instance, the Rescue Agreement Article 5(2) provides that “Each Contracting Party which receives information or discovers that a [S]pace [O]bject or its component parts has returned to Earth […] shall notify the launching authority and the Secretary-General of the United Nations,” Article 5(4) provides that “a Contracting Party which has reason to believe that a [S]pace [O]bject or its component parts discovered in territory under its jurisdiction, or recovered by it elsewhere, is of a hazardous or deleterious nature may so notify the launching authority, which shall immediately take effective steps […] to eliminate possible danger of harm,” and Article 5(5) further provides that “[e]xpenses incurred in fulfilling obligations to recover and return a [S]pace [O]bject or its component parts under paragraphs 2 and 3 of this article shall be borne by the launching authority [emphasis added].” Pursuant to Article 6 of the Rescue Agreement, the term “launching authority” refers to “the State responsible for launching, or, where an international intergovernmental organization is responsible for launching, that organization [emphasis added].”

[58] For instance, the Liability Convention Article 2 provides that “[a] launching State shall be absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its [S]pace [O]bject on the surface of the Earth or to aircraft in flight,” Article 3 provides that “[i]n the event of damage being caused elsewhere than on the surface of the Earth to a [S]pace [O]bject of one launching State or to persons or property on board such a [S]pace [O]bject by a [S]pace [O]bject of another launching State, the latter shall be liable only if the damage is due to its fault or the fault of persons for whom it is responsible,” and Article 4(1) provides that “[i]n the event of damage being caused elsewhere than on the surface of the Earth to a [S]pace [O]bject of one launching State or to persons or property on board such a [S]pace [O]bject by a [S]pace [O]bject of another launching State, and of damage thereby being caused to a third State or to its natural or juridical persons, the first two States shall be jointly and severally liable to the third State…[emphasis added].”

[59] For instance, the Registration Convention Article 2(1) provides that “[w]hen a [S]pace [O]bject is launched into Earth orbit or beyond, the launching State shall register the [S]pace [O]bject by means of an entry in an appropriate registry which it shall maintain. Each launching State shall inform the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the establishment of such a registry,” and Article 3(3) provides that “[e]ach State of registry shall notify the Secretary-General of the United Nations, to the greatest extent feasible and as soon as practicable, of [S]pace [O]bjects concerning which it has previously transmitted information, and which have been but no longer are in Earth orbit [emphasis added].”

[60] For instance, the Rescue Agreement Article 5(3) provides that “[u]pon request of the launching authority, objects launched into outer space or their component parts found beyond the territorial limits of the launching authority shall be returned to…[emphasis added].”

[61] For Instance, the Liability Convention Article 1(b) provides that “[t]he term ‘launching’ includes attempted launching“, and Article 1(c) provides that “[t]he term ‘launching State’ means: (i) A State which launches or procures the launching of a [S]pace [O]bject; (ii) A State from whose territory or facility a [S]pace [O]bject is launched [emphasis added].”

[62] For Instance, the Registration Convention Article 2(1) provides that “[w]hen a [S]pace [O]bject is launched into Earth orbit or beyond, the launching State shall register the [S]pace [O]bject…[emphasis added].” Article 4(1) provides that “[e]ach State of registry shall furnish to the Secretary-General of the United Nations […] the following information concerning each [S]pace [O]bject carried on its registry: […] (c) Date and territory or location of launch; (d) Basic orbital parameters, including: (i) Nodal period; (ii) Inclination; (iii) Apogee; (iv) Perigee; …” and Article 4(3) provides that “[e]ach State of registry shall notify the Secretary-General of the United Nations […] of [S]pace [O]bjects concerning […] which have been but no longer are in Earth orbit [emphasis added].”

[63] The Moon Agreement Art. 3(2).

[64] See supra note 6.

[65] See supra note 23, at 27.

[66] See SIA, Statement of the Satellite Industry Association on the Revised Preliminary Draft Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Space Assets (18 October 2010).

[67] See supra note 23, at 27.

[68] See M.J. Stanford, The Availability of a New Form of Financing for Commercial Space Activities: the Extension of the Cape Town Convention to Space Assets, 1 Cape Town Convention Journal 109, 120-21; R. Goode, Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment and Draft Protocol Thereto on Matters Specific to Space Assets: Explanatory Note, UNIDROIT 2011 DCME-SP-Doc.4, July 2011, last visited (12.10.2022).

[69] See supra note 56, at 112-121.