The Burundi Legal System and Research

By Jean-Claude Barakamfitiye and Janvier Ncamatwi

Jean-Claude Barakamfitiye is a human rights and business lawyer. After graduating from the University of Burundi, he was involved in the International Bridges to Justice Burundi program as a legal volunteer. Registered with the Burundi Bar Association, he started providing legal representation on a pro bono basis to vulnerable detainees, mostly children, women, and the elderly. From 2017 to 2022, he has been the acting Burundi Bridges to Justice (IBJ Burundi) Program manager. He currently works as an IBJ African Regional Juvenile Justice and Youth Coordinator. He holds a degree in Law from the University of Burundi, a master’s degree in Intellectual Property from Africa University in Zimbabwe, and a Graduate Certificate in Peacebuilding and Conflict Transformation from the School for International Training, Vermont, USA.

Janvier Ncamatwi holds a Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Pacific Conflict Resolution. He has been a lawyer at the Burundi Bar Association since 2004. Before joining the Bar, Janvier Ncamatwi worked in the Burundian army, first as a major in the military and then as a military court judge. He has thus a thorough understanding of the Burundian criminal justice system, including the civil and military jurisdictions. Passionate about human rights, Janvier cooperates with several NGOs, including ASF, Ligue Iteka, and the Christian Association Against Torture (ACAT), and is a Legal Fellow at International Bridges to Justice (Burundi office).

Published September/October 2024

(Previously updated in November/December 2012, March 2017, and in March/April 2021)

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Historical Background

- 3. Legal System

- 4. Status of International Law and Ratifications of Relevant Treaties

- 5. Status of Reporting

- 6. National Human Rights Institutions

- 7. National Councils

- 8. New Developments in the Field of Human Rights

- 9. Intellectual Property Rights Protection and Administration Systems

- 10. Additional Remarks

- 11. Burundi Links

1. Introduction

Burundi, a landlocked Republic in Eastern Africa, is bordered on the north by Rwanda, on the east by Tanzania, and the west by Lake Tanganyika and the Democratic Republic of Congo. It has an area of 27,834 square kilometers and is one of Africa’s smallest countries.

Population Information

| Item | Latest figures |

| Total population | 13238559 (2023) |

| Annual population growth rate | 2.7% (2022) |

| Life expectancy at birth | 62 years (2022) |

| Infant mortality rate/1000 | 36.4/1000 (2022) |

| % of the population urbanized | 14.8% (2023) |

| literacy rate, adult total (%of people, ages 15 years and above) | 75.54 (2022) |

| Estimated adult HIV prevalence rate (% of the population aged between 15-49 years) | 1% (2019) |

Figure 1: Burundi’s Population Density and Growth | Source: World Bank, World Databank (Burundi)

The three major ethnic groups that comprise the Burundian population are the Hutu (Bantu) 85%, Tutsi (Hamitic) 14%, and Twa (pygmy) 1%, all recognized in the Burundi Constitution.[1] Since 2014, Burundi has had three officially recognized languages: Kirundi, French, and English. Of these, only Kirundi is spoken by the vast majority of the population. It is recognized as the national language by the Burundian Constitution of 2018.[2]

1.2. Economic Indicators

The Burundian economy depends largely on agriculture and over 55% of the population is poor living under $1 USD a day which is considered below the poverty level.

| Item | Latest figures |

| GNI, Atlas method | 3.117 billion (2022) |

| GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) | 240 (2022) |

| GDP (current US$) | 3.338 billion (2022) |

| GDP PPP (Constant 2021 International US$)[3] | 857.2 |

| GDP growth (annual %) | 1.8(2022) |

| Population below 1 $ a day | 55% |

| Current health expenditure (% of GDP) | 9.1% (2021) |

| Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) | 4.8 (2022) |

| Government expenditure on education, total (% of government expenditure) | 20.6% (2022) |

| Military government expenditure (% of total Government expenditure) | 7.22% (2022) |

Figure 2: A Schematic Attempt at Capturing the Economic Context | Source: World Bank, World Databank (Burundi)

2. Historical Background

2.1. Pre-Colonial History

From the sixteenth century, the region was organized as a kingdom under the authority of a king (mwami) believed to possess both secular and spiritual authority. Hutus, Tutsis, and Batwa cohabited in this kingdom under a system of administration consisting of Hutu and Tutsi chiefs. The two groups became homogenized and adopted the same language (Kirundi). There was territorial expansion and conquest, and the vanquished party was made to pay tribute to the King. The Batwa who lacked a centralized system of governance and were only organized at the family level, were almost always on the receiving end of these conquests.[4]

An examination of how the monarchical system operated during the pre-colonial period, based on oral sources, reveals positive and negative aspects of the system. On the positive side, it may be said that monarchism succeeded in forming a nation and in preserving national unity and social peace. In addition, it established an essentially democratic institution, the ubushingantahe.[5] Lastly, power was perceived as being exercised in the interests of the population at large and for the maintenance of order in society. On the other hand, the monarchical system had inequalities and ethnic differentiation originating from the privileges enjoyed by the ruling class and the institutionalization of the monarchy. Moreover, the power of the monarchy could be arbitrary, despite the existence of institutions for social regulation as the Mwami had an absolute power on the life of all people living in his kingdom and even on their goods.

2.2. Colonial History

The first contact between Burundi and Europeans was with explorers and missionaries. In 1890, the Germans brought Burundi (then called Urundi) under their control. Together with Rwanda (Ruanda) and Tanganyika, this region became known as German East Africa. Adopting a system of “indirect rule,” the impact of German colonization was insignificant. After Germany’s defeat in the First World War, the territory of Ruanda-Urundi was given to Belgium to administer under the League of Nations mandate system. From the outset of its administration in 1916, the Belgians continued a policy of indirect rule. Starting in 1925, it converted the informal societal hierarchies into rigid structures of government.

2.3. Post-Colonial History

When Burundi became independent in 1962, it adopted a constitutional monarchy before becoming a republic after the military coup d’état of 1966. Independence ushered in a period of serious destabilization in the region, characterized by inter-ethnic strife. Large-scale massacres took place in 1965, 1972, 1988, and 1993.

After many years of turbulence, 1993 saw the holding of the first multi-party national elections based on a new constitution, which provided for an inclusive government under a presidential system. Ndadaye Melchior, a Hutu, won the presidential elections, becoming the first member of his community to hold the highest office in the land. His term of office was short-lived, and he was killed three months after ascending office in a coup d’état, which plunged the country into civil war and anarchy. His predecessor, Cyprien Ntaryamira, another Hutu, died in a plane crash with his Rwandan counterpart, Juvenal Habyarimana, which ushered in a period of darkness in the two neighboring countries.

2.4. Current State Structure

2.4.1. The Executive

The President of the Republic is the chief of the executive branch. He is assisted in the execution of the mandate by a Deputy President.[6] While the 2005 Burundi Constitution gave the President of the Republic the power of being both the head of state and government, in the 2018 Constitution, the President is only the head of state.[7] The chief of the Government is the Prime Minister.[8] The President is, in addition, the Commander-in-Chief of the army, the guarantor of national unity, national independence, wholeness of the national territory, and respect of international treaties and agreements ratified by Burundi. He exercises statutory power and execution of the laws.

The former head of state, the late Pierre Nkurunziza, the sole candidate in the 2010 elections, had been re-elected by the population after a first five-year mandate for which he had been elected by the parliament in a vote under the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi approved in a plebiscite in February 2005.[9] In 2015, while the Constitution and the Arusha Agreement stipulated a two-term limit to any elected and re-elected President, President Nkurunziza Pierre was re-elected for a third term after an interpretation of the Constitution given by the Constitutional court legitimizing his candidacy.[10] His re-election fueled a political turmoil that started once his political party declared him a candidate. President Nkurunziza Pierre died when he was going to hand over power to his successor, Ndayishimiye Evariste, leaving behind a controversial legacy. President Nkurunziza Pierre is respected by some because he fought for Burundi’s sovereignty, developed the country, protected the lives of children under 5 years old, and protected women giving birth. He is considered to have been the Supreme Guide of Patriotism by many. On the other hand, many do not share this belief and perceive President Nkurunziza Pierre as the opposite.

Ndayishimiye Evariste subsequently won the elections in 2020. He is a former General of the Army. He has named his government the “Government, which is responsible, Government of Workers.”[11] It is expected that he brings back confidence among many Burundians including those living in exile.

The deputy president is appointed by the Head of State after the National Assembly and the Senate approves separately the candidate deputy-president by vote.[12] The ethnic composition of the Government is Hutu and Tutsi by quotas of 60% and 40% respectively. It also takes into consideration gender sensibility. At least 30% of the members of the government must be women.[13]

2.4.2. The Legislative

Burundi Parliament is bicameral.[14] The National Assembly, together with the Senate, undertakes the legislative function of the state.[15] They also control and monitor the Government’s actions.[16] Nine matters are under the domain of the law:[17]

- Safeguards and fundamental obligations of the citizens: including safeguarding individual freedom; protection of civil liberties; constraints imposed in the interest of national defense and public security to citizens in their person and their property and the protection of morals and culture

- The status of persons and goods: this comprises nationality, status, and capacity of persons; matrimonial regimes, inheritance, and gifts; property ownership, real rights, and civil and commercial obligations.

- The political, administrative, and judicial organization

- The protection of the environment and upkeeping of natural resources

- Financial and patrimonial matters

- Nationalization and privatization of companies

- Education and scientific research regimes

- The goals of economic and social action of the State

- Legislation on labor, social security, and trade union rights, including conditions for exercising the right to strike.

The matters which are not listed above belong to the domain of regulations.

However, Parliament’s law-making function is not absolute. The President may, on the advice of the Constitutional Court, issue a presidential decree which modifies an act of the legislature.[18] The extent of the modification is, however, not clearly defined under the constitution. It leaves one to wonder if there exists the possibility of a Presidential decree completely annulling the objects of legislation. It should also be noted that the Government can request from the Parliament an authorization to make decree-laws around matters that are under the domain of law, for a limited period. Decree-laws that are made under this authorization must be ratified by the Parliament sitting to the next session otherwise, they shall be void.[19] Once again, the Constitution does not clarify the form taken by request from the Government of the authorization to legislate and the procedure followed to grant it.

2.5. The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement

Nowadays, Burundi is recovering from a 15-year civil war. To recover a safe and peaceful state, many peace and ceasefire settlements have been concluded by politicians from both Hutu and Tutsi political parties. The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement of 28th August 2000 is the key and fundamental covenant that has brought a lot of changes in the Burundi legal system and continues to guide peace and reconciliation policy. It was the first settlement that introduced the sharing process of political power between the two main ethnic categories in Burundi by introducing quotas in the composition of the army, the government, the parliament, and even in local administration and public services. It integrates a high gender sensibility by assuring women at least 30% of representation in all instances of decision. Thus, this instrument inspired all the constitutions and acts adopted since 2000.[20]

The Arusha settlement is made of five main protocols:

- Protocol 1: The Nature of the Burundi conflict, problems of genocide and exclusion, and their solutions

- Protocol 2: Democracy and Good Governance

- Protocol 3: Peace and Security for all

- Protocol 4: Rebuilding the country and development

- Protocol 5: Safeguards for implementation of the agreement

Some appendices contain obligations and duties to be observed by signatory parties.

3. Legal System

3.1. Burundian Legal System

Since the colonial period, the judicial system moved from customary law to positive law,[21] and it adopted a civil law system following the example of the Belgians who colonized the country. At independence, positive law covered all branches of law, except some private, civil law issues. After independence, positive law has come to govern almost all the fields of society, with important exceptions related to inheritance, marital property, gifts/liberalities, acquisition and sale of non-registered land, and relationships between employers and workers of the traditional or unstructured sector. A new code of land has been recently adopted. This code states new provisions to allow an easy registration of land. In this way, it is hoped that the field of customary law will decrease. Also, some bills have been proposed to codify the remaining areas covered by customary law.[22]

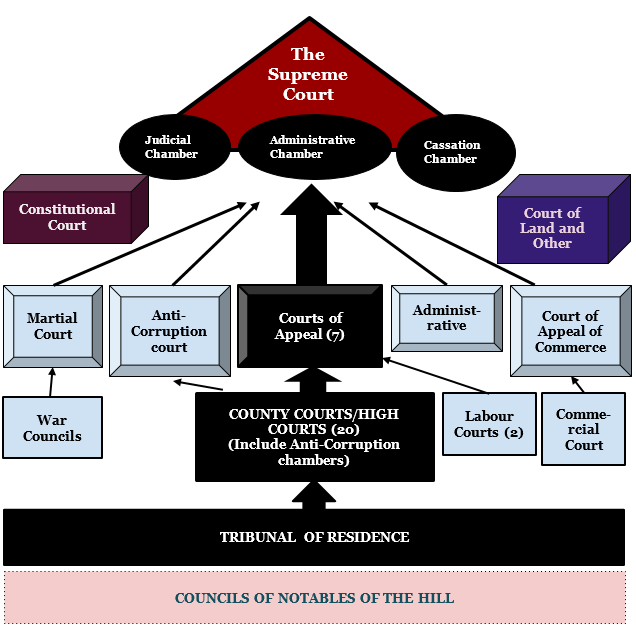

The judicial system was organized through the Code of Organization and Judicial Competence of 17 March 2005,[23] which has been amended by the organic law n°1/26 of December 26, 2023, reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on the code of organization and jurisdiction of courts. The independence of the judiciary is theoretically guaranteed by the constitution, which separates the judiciary, the executive, and the legislative body. There are formal and informal mechanisms of conflict management provided under the Code.

The ratione loci jurisdiction of Burundi courts are still determined following the administrative structure which was in force before the adoption of the Organic Law n°1/05 of March 16, 2023, on the determination and delimitation of provinces, communes, zones, and hills, or districts of the Republic of Burundi. However, as the number and names of provinces and communes have been changed, it can’t be excluded that in the same way, the number of courts and their names will be changed in the future.

At the hill level,[24] a 2021 law has reestablished the Council of Notables of the Hill (Conseil des Notables or Intahe yo ku Mugina) by formalizing the customary regime of conflict settlement at the hill level.[25] The “Intahe yo ku Mugina” was, before, a kind of optional court in which elders “abashingantahe” and elected people on the hills, comprised the bench. Some laws such as the law N°1/03 of 23 January 2021 had conferred upon them the power to arbitrate, mediate, conciliate as well as to settle neighborhood conflicts.[26] Then, an explicit legal recognition of this customary institution was achieved with the 2021 law. The legislature turned the Council of Notables of the Hill into a compulsory conflict settlement mechanism for cases falling within the jurisdiction of the Court of Residence.[27] Therefore, “before any hearing of a civil case within the jurisdiction of the court of residence, the latter verifies that the parties have previously referred the matter to the council of notables.”[28] The Council of Notables of the Hill receives the claims of the plaintiffs and gives their opinion on matters submitted to them.[29] They are vested with the power to hear witnesses.[30] However, they do not adjudicate on cases, their mission is to conciliate.[31] Their opinion is not binding to the judge except when it is promptly accepted by the litigants.[32] However, the judge of the tribunal of residence has to explain why they reject an opinion of the notables of the hill.[33] The conciliatory power of the Council of Notables of Hill is limited to civil matters and civil indemnification resulting from a criminal offense that falls under the jurisdiction of the tribunal of residence.[34] Such councils are not allowed to pronounce a sentence nor can they conciliate any case, including civil cases, that touches on public order and morals.[35]

- The lowest courts with full judicial powers are “Courts of Residence” or Magistrate Courts (Tribunal de Residence). They have been created at commune levels in the rural provinces and at the zone level in the town of Bujumbura.[36] Courts of Residence handle both criminal and civil cases. Courts of Residence have criminal jurisdiction for petty offenses punishable by jail sentences for up to 2 years regardless of the amount of fine.[37] Their jurisdiction over infringement against the highway code has been taken out and bestowed on high courts.[38] The civil jurisdiction of the courts of residence touches a wide range of matters including:

- land disputes regardless of the value;

- disputes between private persons worth up to ten million Burundi francs (around US$3,500 as per the exchange rate of May 27, 2024)

- inheritance-related matters provided that the value of goods at stake does not exceed ten million Burundi francs;

- family and persons-related disputes whose jurisdiction is not conferred to another court;

- disputes that relate to the eviction of a tenant in default. However, this does not include eviction of a tenant engaged in a business lease.[39]

Permanent prosecutors are now to be established in all courts of residence as the Minister of Justice is entitled to appoint one or many prosecutors to play this role before the tribunal of residence seating in criminal matters.[40] This reforms the regime that was applicable before the tribunal of residence since the role of prosecutor in criminal affairs was played by judges who comprise the bench.[41] An improvement that was made by the 2018 criminal procedure code was allowing the prosecutor of the republic to appoint either one or more prosecutors or one or more judicial police officers to play such a role.[42] As this was causing unnecessary delays since the prosecutor had to come from a remote place, to avoid this, a permanent prosecutor was to be appointed to stay closer to the court of residence.

At the provincial level and the commune level in the town of Bujumbura, there are county courts/high courts. High courts have both civil and criminal jurisdictions. For civil jurisdiction, high courts adjudicate on all matters for which either ratione materiae or ratione loci jurisdiction is not entrusted to another jurisdiction.[43] They judge on appeals made on judgments taken by the courts of residence.[44] As far as land matters are concerned and any other case whose worth is not above ten million Burundian francs, they are last resort courts as judgments taken in such cases are not admitted in appeal to cassation.[45] In criminal matters, high courts have jurisdiction to try on all offenses whose jurisdiction is not vested in any other courts.[46] As said earlier, high courts have been given jurisdiction over road traffic code infringements. In addition, an anti-corruption chamber is created in all high courts to judge at a first level on corruption and neighboring crimes-related matters.[47] It is enshrined in the law that high courts can create additional specialized chambers as needed.[48]

Each high court (The Tribunaux de Grande Instance) is paralleled with the prosecutions (Parquets de la République) which are entrusted with the power to “oversee the enforcement of laws, regulations, courts decisions, and other enforceable titles.”[49]

High courts are followed by seven courts of appeal with seven general prosecutions based at Bujumbura (three courts of appeal) and in the old provinces of Ngozi, Gitega, Bururi, and Makamba. The 2023 organic law on jurisdiction and organization of courts provided for a specialized Court of Appeal of Commerce with the authority to receive appeals against decisions taken by the commercial court at the first level and high courts in commercial matters.[50] Ordinary courts of appeal may encompass ordinary civil and criminal chambers as well as specialized ones such as labor and administrative chambers. An appeal chamber in administrative matters is created in all court appeals based in areas where there is no administrative court.[51]

The Supreme Court, with the General Prosecution of the Republic (Parquet Général de la République), stands at the apex of judicial authority and has both original and appellate jurisdictions over civil and criminal matters. The Supreme Court comprises three chambers: the judicial chamber, the administrative chamber, and the cassation chamber. The 2023 organic law on jurisdiction and organization of courts defines the Supreme Court as “the highest ordinary court of the Republic of Burundi. To that end, it is the reference for the place of the judiciary within the institutions of the Republic. It has jurisdictional and administrative control over other courts except the Constitutional court and the Special Court of Lands and Other Properties,”[52] while the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi entrusted to the Supreme Court the responsibility for the proper enforcement of laws.[53]

The Constitutional Court is a sui generis court that presides over matters of a constitutional nature such as providing the right interpretation of provisions of the constitution, validating presidential and legislative elections and plebiscites, and proclaiming their results. The constitutional court ensures respect of the constitution including the Charter of Fundamental Rights by organs of the State and other institutions.[54] Together with the Supreme Court, they constitute the High Court of Justice, which has jurisdiction to try a seating against the president of the republic only in case of high treason and against the President of the National Assembly, the President of the Senate, the Deputy-President of the Republic, and the Prime Minister for crimes committed during their mandate.[55]

Specialized courts including commercial, administrative, labor, and martial courts also exist. The Anti-Corruption Court together with a prosecution and a special brigade, created in 2006, are mechanisms to deal with corruption and public wealth mismanagement matters. This court operates on the same level as courts of appeal.[56] The anti-corruption court is an appealing degree for cases tried at the first level by the anti-corruption chambers created within the high courts and first-level courts for crimes committed by defendants granted a privilege to be judged by the court of appeal as a first-degree court.

Another sui generis court is the Court of Land and Other Properties created to judge affairs that pertain to disputes about land and other properties taking rise in the former civil wars and political crises. These are, for example, the lands or other properties of persons who fled the country for many years and who, after returning, found them occupied by other persons. The court is only competent to judge for first and last resort the appeals lodged against decisions taken by the Commission on Land and Other Properties.[57] The court was mandated to work for 7 years when it was created;[58] then, it was supposed to operate until 2021. However, its mandate has been extended for six years. The term of the Special Court of Land and Other Properties will end three years after the end of the term of the Commission of Land and Other Properties.[59]

3.2. Sources of Law

The operative supreme law is the revised Burundi Constitution adopted through a referendum in 2018.[60] The Constitution empowers parliament to make organic laws as well as statutory laws to give effect to the Constitution and facilitate the conduct of public life within the state.[61] International instruments specifically incorporated by the Constitution are equally directly applicable in the country. However, Burundi has adopted both monist and dualist systems to integrate international instruments.[62]

Regulatory frameworks are envisaged to be developed by administrative bodies and may be modified by legislative procedure upon the advice of the constitutional court.[63] It is explicitly provided also that Presidential Decrees duly advised by the Constitutional Court can modify legislation.[64] The position of customary law however remains uncertain, since the Constitution is silent on this issue. However, the practice is that at the local level, particularly matters of succession and inheritances are governed by customs. Other sources are treaties and international conventions, jurisprudence, and doctrine. There is a more recent compendium of Burundi codes and laws that have been published by the Ministry of Justice with the help of its key partners in 2010. This compendium consists of three tomes that can be found either in printed edition format or soft copies. It was completed in 2013 with an addendum of three times.[65]

Apart from that document, after promulgation, all legal instruments are published in BOB (Bulletin Officiel du Burundi), an official gazette that is published every month. Other institutions have their projects of gathering legal instruments such as Reseau documentaire de l’ Afrique des Grands Lacs, Centre d’Etudes et de Documentation Juridiques (CEDJ), the Main Library of the University of Burundi, and the Department of Judicial and Contentious Affairs of Ministry of Justice, Global Rights. As far as case law is concerned, there are no compendiums of cases as such. However, two times in a magazine of jurisprudence were published in 2012 by the Supreme Court and the Centre d’Etudes et de Documentation Juridique with the support of the Belgian Technical Cooperation. In addition, some cases dealing with special issues (sexual matters) can be found in some NGOs, like Centre Seruka and Association des Femmes Juristes.

There is no system of compilation of cases and other judicial decisions. Each court and tribunal has its system of keeping information on cases that can be found in the relevant court or tribunal. There have been projects of gathering national jurisprudence that have not so far yielded significant results.

3.3. Judicial Structure

4. Status of International Law and Ratifications of Relevant Treaties

The Burundi Constitution, unlike the national constitutions of neighboring countries, has specifically incorporated all human rights instruments ratified. Article 19 of the Constitution provides thus: “The rights and duties proclaimed and guaranteed, human rights treaties duly ratified are an integral part of the Constitution.”[66]

It is submitted that the provisions of Article 19 of the Constitution are radical and far-reaching as all human rights instruments have the force of law, capable of being relied upon in domestic litigation and policy development. Incorporation in this case therefore amounts to domestication and potentially makes Burundi a monist state concerning the human rights instruments duly ratified by Burundi. This progressive prima facie status has however not been tested in courts which may render a different opinion.

Treaties other than human rights treaties that are specifically domesticated by the Constitution require ratification and domestication.[67] The ratification power of the executive is further limited concerning treaties that have the effect of engaging state resources, in which case, specific legislation is required.[68]

5. Status of Reporting

Burundi’s reporting records experience delays.

- Example 1—Under the CAT: In July 2005, Burundi submitted its initial report under the Convention Against Torture, ten years later than it was expected; the intermediary reports were also submitted later than they were expected (Report II, was due on 31/12/2008 but, it was submitted on 19/04/2012; Report III was due on 28/11/2018 but has been submitted on 14/09/2020).[69]

- Example 2—Under CEDAW: The initial report submitted by Burundi under CEDAW was seven years late on 1st June 2000 while it was due on 07/02/1993; for other reporting periods, reports two to four were filed together in 2007 with a delay of two years. The same delay was noted for reports V and VI which were submitted together in 2015. The upcoming report is due on 30 November 2020.[70]

- Example 3—Under the CRC: The initial report on the Convention on the Rights of the Child submitted on 19th March 1998 was submitted six years late on 19/03/1998, while the second report which was due on 17/11/1997 was submitted on 17/07/2008 with eleven years of delay. Report III to V were due on 01/10/2015 and were not yet submitted as of the end of September 2020.[71]

- Example 4—Under the CESCR, CCPR & CERD: The initial report on the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural right (CESCR), which was due in 1992, was submitted 21 years later, on 16 January 2013.[72] The second report is due by 31 October 2020.

However, reporting under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) has been fairly timely for the initial and the second report. The initial and second reports under ICCPR were submitted on time respectively on 4th November 1991 and 11 December 2012. However, the third intermediary report was submitted with a delay of about 2 years on 08 September 2020 while it was due on 3 October 2018. Under the International Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), reports were submitted quite regularly for the initial and the first ten reports. It should be mentioned that the eleventh report which was due on 26 November 1998 is still unsubmitted.[73] State implementation of concluding observations of treaty bodies has not been systematically pursued. While there is evidence that some of the recommendations have been partially implemented, it is also obvious that some recommendations have not been taken seriously by Burundi. This differential approach to implementation reveals a disconnection between the political commitments made by the state and the policy imperatives being pursued. For instance, it can be said that recommendations relating to women have been taken a little more seriously, while those relating to indigenous communities, particularly the Batwa, remain in abeyance. The CERD’s concluding observation recommended thus: “[that] when introducing quotas for ethnic groups, the Government also consider introducing measures, as permitted under article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention and outlined in the Committee’s general recommendation 23 on women in public life, to increase the participation of women in decision-making at all levels. It emphasizes the importance of strict adherence to principles of gender equality in all reconstruction efforts.”[74]

It can be said that the provisions of articles 128, 169, 185, and 213 of the current constitution that guarantee a minimum of 30% women in the Government, the National Assembly, the Senate, and the Judiciary are examples of a response to CERD’s recommendation. This contrasts sharply with the total failure of the state to implement recommendations, such as the concluding observations by the Committee on the Rights of the Child,[75] regarding indigenous minorities such as the Batwa.

6. National Human Rights Institutions

Apart from the Constitutional Court, whose mandate is to interpret the Bill of Rights,[76] the other main public institution tasked with human rights protection and promotion purpose is the Ministry of National Solidarity, Human Rights and Gender (the Ministry), the creation of which is viewed as the highest level of political commitment by the government of Burundi in protecting and promoting human rights. Up to now, the ministry has however failed to undertake any meaningful measures aimed at promoting the constitutional provisions on human rights. Reports of abuse of rights by secret services agents, and police are still rampant, and the existence of the ministry does not seem to have made any difference.[77] Cases of extrajudicial killings have been reported these last years, especially following the 2010 elections and in the furtherance of the 2015 political turmoil by either Burundian civil society organizations, international NGOs like Human Rights Watch or the United Nations Office in Burundi (BNUB)

Despite this, the country established in 2011 the National Independent Commission of Human Rights to monitor state compliance with international standards as well as constitutionally protected rights. In 2012, the Burundi Human Rights Commission received an “A” accreditation as it was considered fully compliant with the Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (Paris Principles) adopted by General Assembly resolution 48/134 of 20 December 1993. However, in the 2016 review, it was recommended to be downgraded to a “B” status,[78] which finally happened since the commission failed to comply with the Paris principles during the one-year notice given to it.[79] In 2021, the Burundi National Independent Commission regained the “A” status, but, unfortunately, it lost it again in 2023 as her independence was deemed a lack by the accreditation body.

Furthermore, the institution of an Ombudsman which is constitutionally sanctioned to receive complaints of state maladministration, including instances of human rights violations,[80] is another nationally relevant institution that plays an important role for the sake of human rights in Burundi.

Moreover, even though in a mood of misunderstanding between multiple stakeholders, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established on December 4, 2014, according to an act of parliament that was promulgated on May 15, 2014, which was modified on November 6, 2018. This law received dissenting opinions from the opposition and many civil society organizations and NGOs. Among others, one can note the comments formulated by Impunity Watch a day before the promulgation of the law. They were concerned with the fact that the law did not include among its key provisions, several recommendations from a national consultation held in 2009. According to Impunity Watch, it was regrettable that the law did not provide for judicial mechanisms to deal with international crimes as this was requested by the population.[81] Thus, they feared that the work of the TRC amounted to a blanket amnesty since the TRC law does not provide expressly for any use of the final report in judicial proceedings against authors of atrocities perpetrated from 1st July 1962 to 4 December 2008 nor does the TRC have linkage to any special court to be created.

That was also the concern of the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of non-recurrence as reiterated by the UNIIB who viewed the mandate attributed to the TRC as a way of de-prioritization of the “truth-seeking” function in favor of the pardon process.[82] Another concern expressed was about the composition of the TRC. Through national consultation, the population has expressed a desire for the inclusion of foreigners,[83] but the TRC does not include any member from a country other than Burundi. The 2018 TRC law did not make progress regarding the fears and criticisms that were formulated against the 2014 law. The 2018 TRC law extends the period covered by investigations to include the colonial time. From then, the work of the TRC covers the period between 26 February 1875 and 04 December 2008. The opinion fears that this period is too long, and the TRC may be unable to efficiently execute its mandate and may partially seek to uncover some facts and fail to equally treat all victims therefore failing to reconcile Burundians.

It was hoped that within this new framework, the Batwa in Burundi would be able to expose the atrocities they have suffered in the context of genocide.[84]

7. National Councils

The Constitution of the Republic of Burundi has established different councils that play key roles related to some particular issues. These councils have been set up to allow the citizens to largely take part in the management of the affairs of the nation.[85] They are:

The National Council for Unity and Reconciliation: It is a consultative committee. Among its main tasks, this council advises on unity, peace, and reconciliation-related issues. It carefully follows Burundi society in the whole process of unity and reconciliation recovery and initiates activities aimed at rehabilitation of the traditional institution of Bashingantahe. The members of this council are nominated by the President of the Republic collaborating with the two deputy presidents. To choose them, the repealed 2005 Constitution had established two criteria: one must be publicly known for his integrity and his high sensitivity to the welfare of the nation and its unity.[86] The 2018 Constitution does not describe the missions, composition, or tasks of this council. It leaves the task to an organic law to be voted to organize such a council and state its duties.

The National Observatory for the Prevention and Eradication of Genocide, War Crimes, and Crimes against Humanity: As it was described by the 2005 Constitution, it is also a consultative committee that regularly monitors Burundi society’s evolution in terms of genocide, war crimes, and other crimes against humanity related issues. This is done to prevent and eradicate the crimes in question. It also promotes the legislation against genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity and monitors its strict implementation.[87] The 2018 Constitution leaves for an organic law to determine the duties of this council, composition, and organization.

The National Council for Security: The 2005 Constitution defined it as a consultative committee that helps the president of the republic and the government to conceive policy in security matters, follows the country in terms of security, and conception of strategies for defense, security, and the upkeep of order in case of crises. Its members are nominated by the President of the Republic.[88] No such definition is included in the 2018 Constitution. An organic law organizes this council.

National Economic and Social Council: As is the case for all the councils listed by Article 274 of the 2018 Burundi Constitution, an organic law defines, organizes, and states the council’s missions. The 2005 Constitution had described it as a consultative body, whose competence involves all economic and social development features of the country that was to be consulted upon every development plan, environment and natural resources conservation, and regional and sub-regional integration.[89]

National Council of Communication: The National Council of Communication is an independent authority that monitors that the freedom of the press is exercised by the law, the public order, and morality.[90] It is a technical council which, besides its consultative role, has the executive power to promote and safeguard the free press.[91] Its members come from the press milieu and news consumers.[92]

The Great Council of the Judiciary (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature): This council is far different from the five others listed above. Its mission is closely connected with the justice sector. The Great Council of the Judiciary plays a key role in the good administration of justice. This council, according to the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi, is the guarantor of the independence of the judiciary. This is the upper disciplinary instance of the judiciary. It receives complaints from citizens or the Ombudsman against the professional behaviors of magistrates. Also, pleas of magistrates concerning their career or appeals against disciplinary actions to magistrates are addressed to this council. The dismissal of magistrates for professional misconduct or incompetency can be done at the request of this council.[93]

However, many criticize the founding of this Council as a move that jeopardized the independence of the Judiciary, despite efforts to the contrary, including bringing the President of the Supreme Court as a deputy president of the council. In my opinion, a council like this one cannot play efficiently its role of safeguarding the independence of the judiciary while chaired by the President of the Republic assisted by the Minister of Justice as secretary.[94]

The Great Council of Prosecution (Conseil Supérieur des Parquets): This is a new body that has created the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi.[95] This new council is tasked to oversee the prosecution and monitor the execution of their duties. An organic law will define its missions and functioning as is the case with the Great Council of the Judiciary.

8. New Developments in the Field of Human Rights

8.1. Criminal Laws and Legal Safeguards of the Accused

In 2009, Burundi adopted a new penal code that abolished the death penalty. It enshrines provisions against torture and other ill-treatment[96] and made a step forward in complying with the provisions of the Rome Statute by punishing international crimes which are defined in the same way as in the Rome Statute.[97] However, this same code criminalizes homosexuality.[98] This provision has been denounced as discriminatory and either international or local human rights organizations claimed for its withdrawal in the criminal code. In December 2017, the criminal code was amended. While preserving major reforms brought by the 2009 criminal code, it kept on criminalizing homosexuality.[99] In addition, the promulgation of the law n°1/14 of 18th October 2016 on the withdrawal of the Republic of Burundi from the Rome Statute, exemplifies a level of regression concerning efforts to fight against impunity.

Following the 2009 penal code, a reviewed criminal procedure code was promulgated on April 3, 2013. The code improved juvenile justice by making it an obligation to provide any child in conflict with the law with legal representation, by obliging in-camera hearings, and by institutionalizing special chambers of children in each high court. In addition, the code integrated a lot of principles to protect human rights. Most importantly as far as legal safeguards of the accused are concerned the code enacts that “freedom is the rule and detention is the exception.” This principle has been stated in the criminal code procedure two times,[100] to highlight how it is a fundamental right of anyone to enjoy freedom. Moreover, complying with the criminal code provisions criminalizing torture, the criminal procedure code provided for the nullity of procedure and any confession obtained under duress.[101] In this way, the 2013 criminal procedure conveyed an intention to humanize criminal justice by enshrining a certain number of legal safeguards for the accused. In 2018, the criminal procedure code was amended. The 2018 amendment does not repeal the above human rights safeguards. However, it has introduced new special investigation techniques that can involve the violation of the rights of individuals including privacy.[102] It has been so far a challenge for the country to overcome violations of human rights. Several cases of arbitrary detentions that amplify the challenging overcrowding of prisons continue to be observed,[103] and the practice of torture strives to be abandoned despite the provisions of the criminal code making it clear that no circumstances, including the state of war or political turmoil, can justify the use of torture.

While talking of torture, it should be noted that on 28 and 29 July 2016 the UN Committee Against Torture undertook a special examination of Burundi under Article 19, §1 of the UN Convention Against Torture; Burundi being the third country, after Israel and Syria, the UN torture watchdog has ever asked to submit a special report ahead of the scheduled four years.[104] It was been done after the UN Committee Against Torture received allegations that torture was widespread and systematically practiced against people who were opposed or perceived to be opposed to the third term of late President Nkurunziza. These allegations were consistent with the findings of the United Nations Independent Investigation on Burundi (UNIIB) established under Human Rights Council Resolution S-24/1.

The UNIIB, in their final report (a report that has been rejected by the Burundi Government), found that “No one can quantify exactly all the violations that have taken place and that continue to take place in a situation as closed and repressive as Burundi during the period covered by UNIIB’s mandate.”[105] In their conclusion, the UNIIB asserted that they “found abundant evidence of gross human rights violations as well as human rights abuses by the Government and people whose actions can be attributed to the Government…”[106] Among the human rights violations found by the UNIIB were allegations of torture and other ill-treatment, arbitrary and unlawful detention as well as mass arrests, and sexual and gender-based violence. The Government of Burundi has denied all these allegations as unfair and exaggerated.

8.2. Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Public Demonstrations

In 2013, Burundi adopted a new very restrictive press law. Here is how the 2015 Freedom House report described the law: “The 2013 media law, which amended a 2003 version, was a serious setback for press freedom. It prescribes punishments including high fines, suspensions of media outlets, and the withdrawal of press cards for several broadly worded offenses, such as publishing or broadcasting stories that undermine national unity and public order, or that are related to issues such as national defense, security, public safety, unauthorized demonstrations, and the economy. The law also limited the protection of journalistic sources, required journalists to meet certain educational and professional standards, and increased the enforcement powers of the National Communication Council (CNC), the media regulator…”[107]

Following the promulgation of the 2013 press law, relationships between private media and the Government worsened since several journalists have been arrested, while others have been called before the prosecutors for investigations purposes.

Without addressing the problems of constitutionality posed by the 2013 press law, the Burundi Constitutional Court on 7 January 2014, after a lawsuit filed by the Union of Journalists, only found that the process according to which fines for press offenses would be assessed was unconstitutional.[108] Unsatisfied with the decision of the Constitutional Court of Burundi, the journalists seized the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) under the Treaty of EAC. The EACJ ruled that the 2013 press law was violating the key provisions of the EAC treaty on freedom of press and expression and urged Burundi to repeal the law or amend Burundi’s obligation under the EAC Treaty.[109]

Following this decision of the EACJ, the press law has been amended and new press law n°1/15 has been promulgated on 9th May 2015, four days before an attack with heavy weapons that destroyed four radio stations in conditions that are hitherto unclarified. Such destruction of private radio stations has been an eloquent sign of regression in terms of the enjoyment of freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

In what relates to freedom of association, assembly, and public demonstrations, after the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi which guarantees those freedoms,[110] the law n°1/28 of 5th December 2013 regulates public demonstrations and assemblies. This law enounces a principle that assemblies and public demonstrations are free in Burundi without being less restrictive as such.[111] It gives strong power to administrative authorities to evaluate whether public demonstrations or meetings would endanger public order and then decide to suspend or cancel them.[112] The undefined concept of “public order” together with these powers vested in administrative authorities have been used several times as grounds for the refusal of public protests as well as meetings organized by political parties or civil society organizations; which undermined the enjoyment of freedom of meetings and demonstration.

In addition, this law obliges any grouping wishing to conduct an assembly or public demonstration to make a declaration to the competent authority four days before the date of the event, the time during which the competent authority will decide whether to delay or ban the assembly or public demonstration if there is a likelihood for the events to endanger public order.[113] In another sense, a declaration to which a ban can be imposed becomes rather an authorization and such a requirement is contrary to the best practices according to which the right to freedom of peaceful assembly does not require the issuance of a permit to be held.[114] It should therefore be noted that spontaneous assemblies or demonstrations are not possible in Burundi because of the aforementioned requirements to be complied with before conducting an assembly or public demonstration.

9. Intellectual Property Rights Protection and Administration Systems

As a member state of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) since 1977,[115] Burundi is progressively modernizing its system of intellectual property rights (IPR) protection and administration. Two newly promulgated laws are the cornerstone of IPR protection in Burundi: The Law No. 1/021 of December 30, 2005, on the Protection of Copyright and Related Rights in Burundi and the Law No. 1/13 of July 28, 2009, on Industrial Property in Burundi. To complement the protection given by these laws, a law on the juridical regime of competition was promulgated in 2010.

9.1. Copyright and Related Rights Protection and Administration System

Copyrights and related rights are protected automatically with no formality in Burundi.[116] Burundi law protects both the moral rights and economic rights of the author.[117] The legal framework of protection of copyrights in Burundi has been strengthened by the ratification, on April 12, 2016, of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and the WIPO Copyright Treaty. However, Burundi is striving to make effective the protection of copyright and related rights since piracy remains among the serious problems that hamper the achievement of an acceptable level of copyright protection.

In 2011, the Government of Burundi created a copyrights and related rights office, the Office Burundais des Droits d’Auteur (OBDA). This office has among other tasks collective management of copyrights. Even though it is still facing some organic challenges, the office has started with awareness-raising activities giving hope of tracking the new era of development of Burundi’s cultural industry shortly.

9.2. Industrial Property Protection and Administration System

The Law No. 1/13 of July 28, 2009, on Industrial Property in Burundi puts in place a comprehensive system of protection of patents, utility models, industrial designs, trademarks, geographical indications, layout designs of integrated circuits, and traditional knowledge. Inventions are protected through a formalized system of applying patent or utility models. The applications are filed with the Department of Industrial Property of the Ministry of Trade and Tourism. Other industrial property rights enjoy protection through the registration system.

There is not yet an autonomous intellectual property office in Burundi. A new intellectual property policy is under discussion. It is hoped that this policy will comprise among other orientations creation of an Industrial Property Office. It should be noted that Burundi, having ratified the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, is not yet a member of the Patent Cooperation Treaty or any regional harmonized filing system. It is expected that Burundi will join the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) since it cooperates with ARIPO with the status of observer.[118]

Also, Burundi has not yet joined the International Trademark Protection organized by the Madrid Agreement and the Madrid Protocol concerning the International Registration of Marks. Again, the country has not yet ratified The Hague Agreement concerning international registration of designs.

10. Additional Remarks

There is a prevailing negative vision of justice that may be attributed to an ethno-political perception of the Burundian system, particularly in criminal matters. The magistrates and the police are thus first perceived according to their ethnic group and seen as biased in favor of it. They are perceived by public opinion as working more for the benefit of the executive and the political parties than working for the goals of justice.

Moreover, the formal system is severely jeopardized by perceptions of impunity and the lack of enforcement of judiciary decisions. In general, the formal judicial apparatus did not manage to deal efficiently with the crisis of 1993 and its effects. “One hears of people saying that the prosecution of the murders and assassinations related to the crisis concern only ‘small fish’ and the ‘big fish’ getaway. Public outcry is specifically directed against cases such as the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye, or crimes against humanity or genocide that are not dealt with even if their final settlement would have gone a long way towards restoring the rule of law.”[119]

The impunity in Burundi is a result of the wrong ruling of the country during the last 58 years. Impunity has been denounced by all parties but in different manners according to ethnic sensibilities. In as much as the Hutu community condemns the repression that took place in 1965, 1972, 1988, and 1993, the Tutsi community also denounced the amnesty given by Buyoya following the events of Ntega and Marangara in 1988 as well as those who committed acts of genocide with the support of FRODEBU in 1993. Also ‘mob justice’ takes encouragement from the impunity for offenses and crimes and is a negation of the justice system. However, some judges are guilty of corruption and other abuses of office. The reconstruction and reconciliation of the communities require that all accused persons should be arrested and brought to trial.

Finally, it must be mentioned that the formal system is severely lacking funds. The economic sanctions on the country taking rise in the political crisis that started in April 2015 came in to worsen the situation.

11. Burundi Links

For further information on Burundi’s Government Institutions, Parliament, the National Commission, and Judicial courts, visit the Burundi government official site.

Media, News, and Information

- Université du Burundi (History of the University, the library, research centers, etc.)

- The University of Pennsylvania Burundi Page

- Burundi News as well as regional news and exclusive interviews

- Studio Ijambo and Radio Isanganiro (radio sponsored by Search for Common Ground-Burundi, formed to reduce ethnic conflict and encourage reconciliation)

- Site for News in English and French

- Site for the Burundi Human Rights League “ITEKA”

- Detailed analysis of the Burundian situation through different original and interactive rubrics

- Africa news

- Agence Burundaise de Presse ABP

Nonprofit NGOs and Foundations

- Search for Common Ground: An NGO based in Washington, D.C. working to reduce ethnic conflict and encourage reconciliation.

- NDI.org: A nonprofit organization promoting democratic institutions in new and emerging democracies. It has 33 pages on how to live in a democracy in Burundi.

- International Foundation for Elections Systems: IFES’s project to support the implementation of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Accords (APRA) and promote community reintegration and stabilization through a sub-grant program-Burundi Initiative for Peace (BIP)

- Human Rights Watch: Contains Burundi-related reports (Info by Country 🡪 Burundi)

- GenocidePrevention.org

- United States Institute of Peace: Preventing genocide in Burundi, lessons from International Diplomacy.

- International Crisis Group – Burundi: Independent organization working to prevent wars and shape policies to build peace.

- Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

Economy, Business, and Trade

Churches

- National Council of Burundi Churches

- An Evangelical Christian Mission Agency working in partnership with the Anglican Church in Burundi, Rwanda, south-western Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo

Others

- US Agency for International Development – USAID assistance to Burundi

- Information by country – Burundi

- CIA The World Factbook – Burundi

[1] However, the definition of an ethnic group cannot be applied to the Burundian context. This because apart from the Batwa ethnic group that exhibits some differences making them to be known as indigenous people, all three groups share the same territory, culture, and language.

[2] See, Languages of Burundi, Wikipedia (accessed on January 28, 2021).

[3] GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP GDP is gross domestic product converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity rates. An international dollar has the same purchasing power over GDP as the U.S. dollar has in the United States.

[4] Lewis J, The Batwa Pygmies of the Great Lakes Region 5 (2000).

[5] It is a traditional institution of elders which was handling disputes.

[6] Article 93 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[7] Article 96 of Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[8] Article 126 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[9] The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi signed in 2000 under the mediation of Presidents Nyerere and later Mandela provided the link during the period of constitutional crisis in Burundi. See the Mwalimu for instance (assessed January 28, 2021).

[10] Judgement RCCB 303, Constitutional Court, 4 May 2015.

[11] Original name of the Government in Kirundi “Reta Mvyeyi, Reta Nkozi.”

[12] Article 123 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[13] Article 128 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[14] Article 152 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[15] Article 163 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Article 164 of The Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[18] Article 165, under §2 of The Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[19] Article 200 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[20] One can refer to the preamble of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[21] Country Profile: Burundi.

[22] The bill related to inheritance was submitted to the Parliament in 2005, but no decision has been yet taken. Also, Ntahombaye, PhD. and Kagabo, L, ‘Mushingantahe Wamaze Iki? –The Role of the Bashingantahe during the crisis’, University of Burundi (2003).

[23] Promulgated pursuant to article 205 para.3 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[24] This is the basic administrative unity.

[25] Law N°1/23 of 23 January 2021 supplementing the provisions of the code of civil procedure relating to the reestablishment of the council of notables of the hill.

[26] Article 46, 2° of the Law n°1/33 of 28 November 2014 revising the law N°1/02 of 02 January 2010 organizing the communal administration.

[27] Article 5, 1° of Law N°1/23 of 23 January 2021 supplementing the provisions of the code of civil procedure relating to the reestablishment of the council of notables of the hill.

[28] Article 15, §2.

[29] Article 5, 1°.

[30] Article 11, 4°.

[31] Article 5, 2°.

[32] Article 16, 1°. Article 13.

[33] Article 16, 2°.

[34] Article 5, 1°. Article 5, §2 of Law N°1/23 of 23 January 2021 supplementing the provisions of the code of civil procedure relating to the reestablishment of the council of notables of the Hill and Article 18 of the Organic law n°1/26 of December 26, 2023, reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on organization and jurisdiction of courts, BOB N° 12 QUATER /2023, 4095-4141.

[35] Article 5, 2°.

[36] Provinces and communes are still numbered and organized according to the repealed administrative structure’s legal regime. However, after the 2025 elections, Burundi will count no more than five provinces and 42 communes as per article 5 of the 2023 administrative structure organic law which says: “Burundi is divided into five (5) provinces, forty-two (42) Communes, four hundred and fifty one (451) zones and three thousand and forty-four (3044) hills or districts (quarters)” and article 7 providing for the time the reform will enter in force.”

[37] Article 14 of the Organic Law n°1/26 of December 26, 2023, reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on organization and jurisdiction of courts, BOB N° 12 QUATER /2023, 4095-4141.

[38] Article 32, §2.

[39] Article 19; §1, 1°-5° & §2.

[40] Article 17, §2.

[41] Article 11 of the Code of Organization and Judicial Competence of 17 March 2005.

[42] Article 86, §2 of the Law N°1/09 of 11 May 2018 on Criminal Procedure Code.

[43] Article 36 of the Organic Law n°1/26 of December 26, 2023, reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on organization and jurisdiction of courts, BOB N° 12 QUATER /2023, 4095-4141.

[44] Article 37.

[45] Article 38, §2 of the Organic Law n°1/26 of December 26, 2023, reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on organization and jurisdiction of courts, BOB N° 12 QUATER /2023, 4095-4141.

[46] Article 32, §1.

[47] Article 29.

[48] Article 30.

[49] Article 194.

[50] Article 72.

[51] Article 42.

[52] My translation of: “La Cour Suprême est la plus haute juridiction ordinaire de la République du Burundi. Elle constitue à ce titre la référence pour la place du pouvoir judiciaire au sein des institutions de la République. Elle exerce le contrôle juridictionnel et administratif sur les autres juridictions la Cour Constitutionnelle et la Cour Spéciale des Terres et autres Biens.” See Organic Law n°1/26 reviewing the law n°1/08 of March 17, 2005, on organization and jurisdiction of courts, BOB N° 12 QUATER /2023, page 4095-4141, Article 4.

[53] Article 227 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018)

[54] Article 234 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[55] Article 240 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[56] Law N°1/36 of 13th December 2006 creating the Court Against Corruption.

[57] Article 15, Law n°1/08 of 13 March 2019 revising Law n°1/26 od 15th September 2014 on the establishment, organization, composition, functioning, and jurisdiction of the special court for land and other property as well as the procedure before it.

[58] Article 3, Law n°1/26 od 15th September 20114 on the special court of land and other properties and the procedure applicable before it.

[59] Article 103 of the Law on the Special Court of Land and Other Properties (2019).

[60] While there is no explicit provision on the supremacy of the Constitution, the same can be inferred from Article 234, §2 of the Constitution, which empowers the constitutional court to determine the constitutionality of laws, international treaties, and Internal regulations of the National Assembly and the Senate. It is thus assumed that inconsistency with the constitution will invalidate the other laws, which by parity of reasoning rank lower than the constitution.

[61] Article 163 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[62] Article 279 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018). Article 277 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[63] Article 165 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[64] Ibid.

[65] See Codes et Lois du Burundi (Last accessed on 25/09/2020).

[66] The 2018 Constitution of the Republic of Burundi does not name human rights instruments as was the case with Article 19 of the 2005 Constitution. This formulation is more progressive as it has given the same consideration to all human rights instruments ratified by Burundi. On the other hand, the new article 19 is considered a setback to some extent since it has taken out paragraph 2 which states as follows: “These fundamental rights are not the object of any restriction or derogation, except in certain circumstances justifiable by the general interest or the protection of a fundamental right.”

[67] Article 277 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[68] Article 279 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[69] See OHCHR (accessed on January 28, 2020).

[70] Idem.

[71] Ibid.

[72] See the OHCHR UN Treaty Body Database.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Burundi. 02/02/2001.accessed from here (assessed on20-4-2007).

[75] Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Burundi. 16/10/2000 CRC/C/15/Add.133. (Paragraphs 77 & 78).

[76] Article 234 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[77] See Lemarchand R, Burundi’s Endangered Transition (2006) here (assessed January 28, 2021).

[78] GANHRI, Chart of the status of national institutions accredited by the global alliance of national human rights institutions, Accreditation status as of 26 May 2017, (as archived by the Internet Archives on Sept 22, 2023)

[79] Idem, Accreditation status as of 27 November 2019 (as archived by the Internet Archive on October 25, 2020). See also Ganhri – Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions, https://ganhri.org/.

[80] The office of the Ombudsman is established by Article 243 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018) to receive complaints of administrative maladministration, including human rights violations.

[81] Impunity Watch, Press Release of May 14, 2014.

[82] A/HRC/33/37, p. 17.

[83] 77 percent of the population consulted supported this idea. See Rapport des consultations nationales sur la mise en place des mécanismes de justice transitionnelle au Burundi, p.73.

[84] Batwa victimization in the context of the genocide has been documented by Minority Rights Group International, among others. See for instance here (assessed 30-2-2007).

[85] Article 275 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[86] Articles 269-273 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[87] Articles 274-276 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[88] Articles 277-279 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[89] Articles 280-283 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005).

[90] Article 1, §2 of the Law N ° 1/06 of 8 March 2018 amending Law No. 1/03 around missions, composition and functioning of the National Council of Communication.

[91] Article 6, Idem.

[92] Article 16, Idem.

[93] Articles 215-217 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[94] About the presidency of the Great Council of Justice, see the Article 224 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018).

[95] Article 226 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2018)

[96] Article 204 to 209 of the penal code of Burundi (2009).

[97] Article 195 to 203 of the penal code of Burundi (2009).

[98] Article 567 of the penal code of Burundi (2009).

[99] Article 590 of the Burundi Criminal Code (2017).

[100] Article 52 and Article 110 of the Criminal Procedure Code (2013).

[101] Article 180, §2 of the Criminal Procedure Code (2013).

[102] Article 47-84 of the Criminal Procedure Code (2018).

[103] The occupation of prisons is rated over 200% of the regular welcoming capacity of all the 11 prisons.

[105] A/HRC/33/37, p.7.

[106] A/HRC/33/37, p.19.

[107] Freedom House – 2015 Burundi Report. (as archived by the Internet Archives on Jun 11, 2017).

[108] Decision of the Constitutional Court of Burundi of 7 January 2014, pp.10,12.

[109] Burundian Journalists’ Union vs. the Attorney General of the Republic of Burundi, Reference No. 7 of 2013.

[110] Article 32 of the Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (2005) which became Article 31 in the 2018 Constitution of the Republic of Burundi.

[111] Article 1, Law n°1/28 of 5th, December 2013.

[112] See inter alia, article 4 §4; article 8 §2in fine, article 10 §1, Article 12 § 3.

[113] Article 4 and Article 7.

[114] International Center for Not-for-Profit Law – Burundi (last accessed March 4, 2021).

[116] Article 3§2 of Law No. 1/021 of December 30, 2005, on the Protection of Copyright and Related Rights in Burundi (2005).

[117] Chapter IV of Law No. 1/021 of December 30, 2005, on the Protection of Copyright and Related Rights in Burundi (2005). Chapter V of Law No. 1/021 of December 30, 2005, on the Protection of Copyright and Related Rights in Burundi (2005).

[119] Ntahombaye, Ph. and Kagabo, L as above.