Macau Special Administrative Region of People’s Republic of China Jurisdiction

Raquel Ferreira Pedrosa Alves is a Portuguese lawyer registered at the Portuguese Bar Association since 2005. Currently, Raquel is a Senior Legal Adviser working in the fields of administrative law, public procurement, corporate law and compliance at Transportes Metropolitanos de Lisboa, responsible for managing the public road transport service in Lisbon Metropolitan area and the technological platform integrating the ticketing and public information system, as well as for developing studies and plans, and implementing accessibility, mobility and transport policies. Previously, she worked as a Regulatory & Legal Adviser in the areas of administrative and public law, regulation, electronic communications, e-commerce and space law at Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações (ANACOM)/National Communications Authority in Portugal.

Raquel earned her LL.B. from the Faculty of Law at Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal (1998-2003) and Advanced LL.M. in International Business Law from Católica Global School of Law, Portugal and Duke University School of Law, USA (2015/2016). She also earned a master’s degree in Transnational Law from Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon School of Law, Portugal (2017-2019) with the master thesis titled “Advance Directives – What Can We Learn from the American Advance Care Model?” Through the years, she has also completed several courses on data protection, digital security, compliance, and public procurement, as well as in telecoms regulations and legal drafting. Between 2007 and 2015, Raquel lived and worked in Macau Special Administrative Region of People’s Republic of China (Macau) first as an Associate Lawyer in a Luso-Chinese law firm, in which she provided legal services and advice in the fields of corporate law, contracts, labor and litigation procedures, and later worked as a Legal Adviser at the Macau Government Health Bureau in the areas of public, administrative, and health law. Raquel is a permanent resident of Macau and is also registered at the Macau Lawyers Association.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction and General Background

- 2. Macau as an “Autonomous” Region: Legal and Economic Features

- 3. Executive Power

- 3.1. Chief Executive

- 3.2. General Secretariats

- 3.3. Executive Council

- 3.4. Other

- 4. Legislative Power

- 5. Judiciary

- 5.1. Courts

- 5.2. Public Prosecutions Office

- 6. Sources of Law

- 6.1. Legislation

- 6.2. Customary Law and Equity

- 6.3. Case Law

- 6.4. Doctrinal Work

- 7. Legal Education and Professional Organizations

- 8. Health System

- 9. Useful Links, Portals, and Databases

- 10. Bibliography and Other Sources

1. Introduction and General Background

The Portuguese arrived in Macau in the year 1557 and settled in the territory for nearly 500 years. After an initial period of mixed Chinese-Portuguese jurisdiction from 1557 to 1849, there was a colonial period between 1849 and 1974. A post-colonial period followed, in which Macau was under Portuguese administration until the end of 1999, the year of its transfer of sovereignty to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Since December 20, 1999, Macau is a Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of the PRC. According to Article 31 of the PRC Constitution, “The State may establish special administrative regions when necessary. The systems to be instituted in special administrative regions shall be prescribed by law enacted by the National People’s Congress in the light of specific conditions.” Similar to Hong Kong, Macau enjoys a high degree of autonomy from mainland China under the so-called principle of “one country, two systems.”

Macau is endowed with Macau Basic Law,[1] adopted by the Eighth National People’s Congress at its First Session on March 31, 1993. It is the main legal document of the Special Region, which defines the social and economic system applicable to the MSAR, its administration, legislation, and justice system. It also provides a constitutional framework for the region, establishing a list of fundamental freedoms, rights, and guarantees for its residents. According to this legal document, private ownership was safeguarded, and the liberal capitalism system inherited from the Portuguese system remained in place.

Geographically Macau is located on the southeast coast of China, west of the Pearl River Delta, adjacent to Guangdong Providence, 60 km from Hong Kong and 145 Km from Guangzhou city. Today Macau and Hong Kong are connected by the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, the world’s longest sea bridge crossing with a total length of 55 km.

Macau is a very small region occupying approximately 32.9 square kilometers, being the most densely populated city in the world. It is comprised of a peninsula named Macau and two islands, Taipa and Coloane, both linked by the Cotai causeway, a piece of land (the Cotai strip) reclaimed from the sea, nowadays with many hotels, casinos, and entertainment venues.

According to the Macau Statistics and Census Service Bureau (Direcção dos Serviços de Estatística e Censos), the population by census results showed that the population of the region reached 671.94 in the third quarter of 2022. Total population at the end of the third quarter decreased by 5,400 quarter-to-quarter, due to a drop in number of non-resident workers living in Macau. In 2021 (and according to the last data available at the Bureau online), population density stood at 20,700 persons per square kilometer.

With particular characteristics, Macau is a bilingual region in China with two official languages: Chinese (in its Cantonese variant) and Portuguese. Both languages are used in all government departments, including the local courts and the Legislative Assembly, as well as in all official documents. Macau is a Special Region that has long been characterized for its mix of Chinese, Portuguese, and Macanese culture. It has been regarded as an important historical gateway by which the Western civilization entered in China. In 2005, the Historic Center of Macau, comprised of a unique blend of Portuguese and Chinese ancient and historical buildings, was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

2. Macau as an “Autonomous” Region: Legal and Economic Features

Per the Joint Declaration of the government of the PRC and the government of the Republic of Portugal on the question of Macau, signed on April 13, 1987, for a period of fifty years from the handover (until 2049), Macau would enjoy a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defense affairs (matters of the responsibility of the Central People’s Government).[2] This means that Macau is vested with its own executive, legislative, and independent judicial powers, including that of final adjudication. Macau also benefits from financial and monetary autonomy with its own currency, the Macanese pataca (MOP) that continues to circulate and remains freely convertible. The pataca is linked to the Hong Kong dollar (HKD), the exchange rate usually quoted in Macau as 1.03 MOP. See Banco Nacional Ultramarino BNU online, for more information on the exchange rate.

Macau is widely based in the Portuguese law, thus belonging to the civil law tradition, with its major codes, the Civil Code, Civil Procedure Code, Criminal Code, and Criminal Procedure Code, drafted originally in Portuguese and equivalent to the ones that exist in Portugal. In terms of commercial law, however, the code includes some legal instruments typical from common law, which makes it a type of hybrid law. Due to the proximity of other regions and countries like Hong Kong and Singapore, the two major financial centers in Asia with different legal systems, there was a need to adapt the Commercial Code to the specific needs of the Special Region. An example is the introduction of the “floating charge”, a type of guarantee that can be granted over all present and future assets of a company provided that certain requisites are fulfilled, regulated in Articles 928 to 941 of the Commercial Code.

Moreover, Macau has a special tax regime making it very attractive for foreign investors. In terms of corporate income tax (imposto complementar de rendimentos), applicable to companies and individuals that carry on an industrial or commercial activity in the Region, per the MSAR Budget for 2023 approved by Law no. 19/2022 (the 2023 MSAR Budget), the tax-free income threshold for complementary tax is MOP 600 000,00 for income derived in the tax year 2022, whereas income above that threshold is taxed at a 12% rate. Companies have been exempted from the industrial tax (contribuição industrial) for many years now. In relation to personal taxation (imposto profissional), as established by the 2023 MSAR Budget, there is a deduction of 30% to the tax payable and the first MOP 144,000 of annual assessable income is exempted from professional tax. In addition, the 2023 MSAR Budget establishes a corporate income tax exemption for income obtained or sourced in Portuguese-speaking countries, provided that it was taxed in such countries, and also creates higher deductions for expenses linked to innovation, science, and technology activities. Economically speaking, in 1992 (still under Portuguese administration) Macau executed an agreement for trade and cooperation with the former European Economic Community, mainly to extend and deepen economic and trade relations or exports between the parties. Internationally, Macau is known for its good relations worldwide, including with Portugal, and it is a member of the World Trade Organization. In 2003, the Governments of Macau and the PRC also signed the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (see CEPA) to promote the economic and trade exchange cooperation. Under the agreement, that has been officially implemented since 2004, Macau goods exported to mainland China are not subject to customs tariffs. Moreover, companies incorporated in Macau and professionals of service industries enjoy some relevant benefits to enter and invest in mainland markets. On November 20, 2019, an agreement concerning amendment to the CEPA agreement on trade in services was signed, entering into force on June 1, 2020, providing more convenient conditions for Macau’s enterprises and service suppliers to develop the Mainland market. See the Economic Bureau (Direcção dos Serviços de Economia e desenvolvimento Tecnológico) for more information.

The main components of Macau economy are tourism and gambling. The liberalization of Macau’s gaming industry in 2002 ended the monopoly that had lasted since 1962, which belonged to the Tourism and Entertainment Company of Macau Limited (also known as “STDM”), a company owned by Stanley Ho and his family.[3] The Macau Gaming Law (Law no. 16/2001, last amended by Law no. 7/2022) enabled a competitive gambling industry environment in the Region by establishing that three new gaming concessions would be granted through an international tender process. Since 2002, there are three casino gaming concessions operating: Wynn Resorts (Macau), S.A.; Galaxy Casino, S.A.; and Sociedade de Jogos de Macau (SJM), this last one with its major shareholders being STDM and Stanley Ho. Later on, three additional sub-concessions were authorized to operate in the Region. The Macau Government granted sub-concessions from Galaxy to Las Vegas Sands (the Venetian Macau, S.A.), from SJM to a joint venture between MGM and Pansy Ho, and from Wynn Resorts to a joint venture between Melco and Crown. In 2019, SJM and MGM Grand Paradise, S.A. have been granted two-year extensions to their casino licenses. Although at first all concessions would expire on June 26, 2022 (see the press release issued on March 15, 2019 by the Government), afterwards Macau’s Government has officially extended the Special Administrative Region’s six gaming licenses until December 31, 2022 (see the press release issued on June 23, 2022 by the Government). On June 22, 2022, changes to the Gaming Law were approved by the Legislative Assembly, marking the biggest reform in two decades. The new law (Law no. 7/2022) introduces several important measures, such as eliminates sub-concessions, reduces the concession period from 20 to 10 years, caps the number of tables and slots and limits junkets to one concessionaire each, among others. See the Macau Gaming History for more information on new casino gaming concession contracts effective as of January 1, 2023.

From a fishing and trading port in the mid-sixteenth century, strategically located in the southeast coast of China in the west of the Pearl River Delta, Macau has evolved in the beginning of the twenty-first century into the world’s biggest gambling hub, superseding Las Vegas revenue. At the end of 2019, the accumulated gross revenue of the gaming industry was 292,455 billion patacas, approximately 32.4 billion euros. See the Monthly Gross Revenue from Games of Fortune in 2019 and 2018 released by the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau (Direcção de Inspecção e Coordenação de Jogos). Macau is nowadays frequently named as “Las Vegas of Asia.” At the end of 2019 there were a total of 41 casinos operating in the Region.

However, in 2020 and in 2021 the gross gaming revenue came to 60,441 billion patacas and 86,863 billion patacas, respectively (see the Monthly Gross Revenue from Games of Fortune in 2021 and 2020). In the end of 2022, the gross gaming revenue came to 42,198 billion patacas, down 51.4% on 2021, and the lowest single year total since the year of 2004 (with a gross gaming revenue of 41,378 billion patacas), a major impact due to COVID-19 outbreak and travel/border restrictions, with much of its gaming workforce being unavailable (see the Monthly Gross Revenue from Games of Fortune in 2022 and 2021).

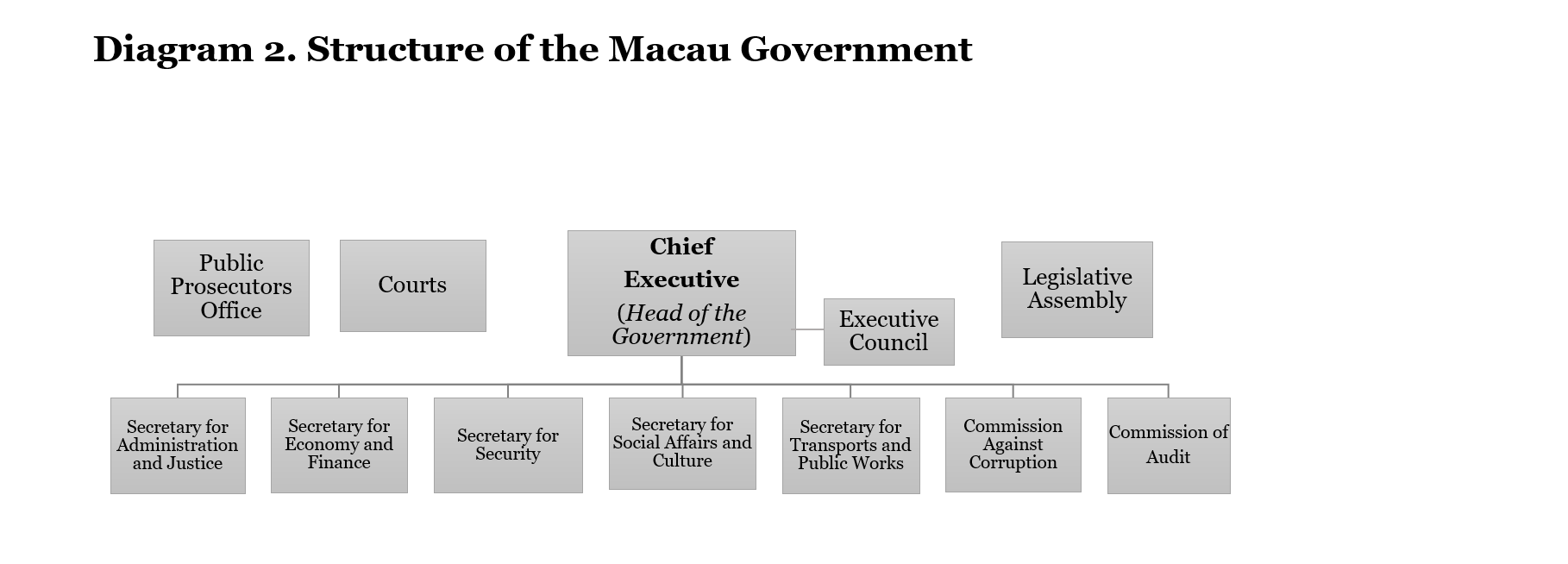

3. Executive Power

3.1. Chief Executive

The Government of Macau is the executive authority of the Region led by a Chief Executive (Chefe do Executivo)—Articles 61 and 62 of the Macau Basic Law—with broad policymaking and executive powers, although still accountable to the Central People’s Government and the MSAR in accordance with the provisions of the Basic Law. See Office of the Chief Executive of MSAR.

Per Article 47 of the Macau Basic Law (the constitutional document of the MSAR), “The Chief Executive of the Macau Special Administrative Region shall be selected by election or through consultations held locally and be appointed by the Central People’s Government.” The Chief Executive shall be elected by an Election Committee composed by three hundred members of industrial, commercial and financial sectors, as well as of cultural, educational, labour, social, and religious sectors and is appointed by the Central People’s Government. The specific method for selecting the Chief Executive is established in Annex I of the Macau Basic Law. The Chief Executive shall be a Chinese citizen of not less than 40 years of age and a permanent resident of the Region who has ordinarily resided in Macau for a continuous period of not fewer than 20 years (Article 46 of the Macau Basic Law). The term of office is five years, and no individual may serve for more than two consecutive terms (Article 48 of the Macau Basic Law).

According to Article 50 of the Macau Basic Law, besides leading the Government of the Region, the Chief Executive is responsible for:

- the implementation of the Basic Law and other laws applicable in the Special Region

- signing bills passed by the Legislative Assembly and to promulgate laws

- signing budgets passed by the Legislative Assembly and report the budgets and final accounts to the Central People’s Government for the record

- deciding on government policies and issuing executive order

- formulating the administrative regulations and promulgating them for implementation

- nominating and reporting to the Central People’s Government for appointment the following principal officials:

- Secretaries of Departments

- Commissioner Against Corruption

- Commissioner of Audit

- leading members of the Police and the Customs and Excise

- recommending to the Central People’s Government the removal of the above-mentioned officials

- appointing part of the members of the Legislative Assembly

- appointing or removing members of the Executive Council, as well as presidents and judges of the courts at all levels and prosecutors in accordance with legal procedures

- nominating and reporting to the Central People’s Government for appointment of the Prosecutor-General and recommending to the Central People’s Government the removal of the Prosecutor-General in accordance with legal procedures

- appointing or removing holders of public office in accordance with legal procedures

- implementing the directives issued by the Central People’s Government in respect of the relevant matters provided for in the Basic Law

- conducting, on behalf of the Government of the Region, external affairs and other affairs as authorized by the Central Government Authorities

- approving the introduction of motions regarding revenues or expenditure to the Legislative Assembly

- deciding, in the light of security and vital interests, whether government officials or other personnel in charge of government affairs should testify or give evidence before the Legislative Assembly or its committees

- conferring medals and titles of honour of the Special Region in accordance with the law

- pardoning persons convicted of criminal offences or commute their penalties in accordance with the law

- handling petitions and complaints

Since December 2019, Ho Iat Seng (in Chinese: 賀一誠; born June 12, 1957) is the Chief Executive of Macau. On December 20th, Ho Iat Seng was formally sworn into office as the fifth Chief Executive of MSAR. See GOV.MO Macau SAR Government Portal, Chief Executive.

3.2. General Secretariats

The Government of Macau also comprises five General Secretariats (Secretarias Gerais) (see Law no. 2/1999 and GOV.MO Macau SAR Government Portal, Departments and Agencies):

- Administration and Justice affairs – see the Office of the Secretary for Administration and Justice (Gabinete do Secretário para a Administração e Justiça)

- Economy and Finance affairs – see the Office of the Secretary for Economy and Finance (Gabinete do Secretário para a Economia e Finanças)

- Security affairs – see the Office of the Secretary for Security (Gabinete do Secretário para a Segurança)

- Social Affairs and Culture affairs – see the Office of the Secretary for Social Affairs and Culture (Gabinete da Secretária para os Assuntos Sociais e Cultura)

- Transports and Public Works affairs – see the Office of the Secretary for Transport and Public Works (Gabinete do Secretário para os Transportes e Obras Públicas)

Moreover, it is composed by directorates of services, departments and several divisions (Article 62 of the Macau Basic Law). The principal officials of the MSAR shall be Chinese citizens who are permanent residents of the Region and have ordinarily resided in Macao for a continuous period of no fewer than 15 years. At the time of assuming office, all shall declare their property to the President of the Court of Final Appeal of the MSAR for record purposes (Article 63 of the Macau Basic Law).

In general, the Government has the following powers and functions: to formulate and implement policies, to conduct administrative affairs, to conduct external affairs as authorised by the Central People’s Government under the Basic Law, to draw up and introduce budgets and final accounts, to introduce bills and motions and to draft administrative regulations, and to designate officials to sit in on the meetings of the Legislative Assembly to hear opinions or speak on behalf of the Government (Article 64 of the Macau Basic Law).

It must abide by the law, and it is accountable to the Legislative Assembly of the Region. It shall implement laws passed by the Assembly and already in force, it shall present regular policy addressed to the Assembly, and it shall answer questions raised by the deputies of the Assembly (Article 65 of the Macau Basic Law).

3.3. Executive Council

The executive structure also includes the Executive Council (Conselho Executivo), an organ that assists the Chief Executive in policymaking (Article 56 of the Macau Basic Law). Members of the Executive Council shall be appointed by the Chief Executive from among the principal officials of the executive authorities, members of the Legislative Assembly, and public figures. Its members shall be Chinese citizens who are permanent residents of the Region, and it shall be composed of seven to eleven persons. The Chief Executive may, as he or she deems necessary, invite other persons concerned to sit in on meetings of the Council (Article 57 of the Macau Basic Law).

The Executive Council shall be presided over by the Chief Executive. The meetings of the Executive Council shall be held at least once a month. Except for the appointment, removal, and discipline of officials and the adoption of measures in emergencies, the Chief Executive shall consult the Executive Council before making important policy decisions, introducing bills to the Legislative Assembly, formulating administrative regulations, or dissolving the Legislative Assembly (Article 58 of the Macau Basic Law).

3.4. Other

At the level of the executive power, there are other official officers that play an important role in Macau. On the one hand, the Commission Against Corruption (Comissariado contra a Corrupção), among other functions, carries out preventive actions against acts of corruption or fraud. On the other hand, a Commission of Audit (Comissariado da Auditoria) was also established as an autonomous and independent government body, having as its main duties to audit the Macau Government’s general accounts and the financial operations of government departments and entities as well as government-funded projects and organizations. Both Commissions are accountable to the Chief Executive (Articles 59 and 60 of the Macau Basic Law). There are also the Unitary Police Service (Serviços de Polícia Unitários) and the Macao Customs (Serviços de Alfândega). See Law no. 2/1999.

4. Legislative Power

4.1. Legislative Assembly

Macau enjoys legislative power, and, per Article 67 of the Basic Law, the Legislative Assembly (Assembleia Legislativa) shall be the legislature of the Region. The Legislative Assembly shall be composed of permanent residents of the Region. Most of its members shall be elected. The method for forming the Assembly is established in Annex II of the Basic Law (Article 68 of the Macau Basic Law). In the first term, the Legislative Assembly shall be formed in accordance with the decision of the National People’s Congress of the PRC. If there is a need to change the method for forming the Legislative Assembly in or after 2009, such amendments must be made with the endorsement of a two-thirds majority of all the members of the Assembly and the consent of the Chief Executive, and they shall be reported to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for record. The method for electing members of the Legislative Assembly shall be specified by an electoral law introduced by the Government of Macau and passed by the Legislative Assembly. The Election System of the Legislative Assembly of the MSAR was established by Law no. 3/2001 (last amended by Law no. 9/2016 and republished by Dispatch of the Chief Executive no. 21/2017).

Upon assuming their office, the members of the Legislative Assembly shall declare their financial situation (Article 68 of the Macau Basic Law). The term of office of the Legislative Assembly shall be four years, except for the first term of office that ended on October 15, 2001 (Article 69 of the Macau Basic Law). The Chief Executive has the power to dissolve the Legislative Assembly in accordance with the provisions of the Basic Law (Article 70 of the Macau Basic Law). The Legislative Assembly has the following powers and functions:

- to enact, amend, suspend or repeal laws in accordance with the provisions of the Basic Law and legal procedures

- to examine and approve budgets introduced by the government and to examine the report on audit also introduced by the Government

- to decide on taxation according to Government motions and approve debts to be undertaken by the Government

- to receive and debate the policy plan addressed of the Chief Executive

- to debate any issue concerning public interest

- to receive and handle complaints from Macau residents

If a motion initiated jointly by one-third of all members of the Legislative Assembly charges the Chief Executive with serious breach of law or neglect of duty, and if he or she refuses to resign, the Assembly may, by a resolution, give a mandate to the President of the Court of Final Appeal to form an independent investigation committee to carry out an investigation. If such committee considers that the evidence is sufficient to substantiate such charges, the Council may pass a motion of impeachment by two-thirds majority of all its members and report it to the Central People’s Government for decision. It can summon persons concerned to testify or give evidence as required when exercising the abovementioned powers and functions (Article 71 of the Macau Basic Law).

4.2. The President and the Vice-President

The Legislative Assembly has a President and a Vice-President elected by and among the members of the Assembly. Both shall be Chinese citizens and permanent residents of Macau that have resided in MSAR for a continuous period of not fewer than 15 years (Article 72 of the Macau Basic Law). The Vice-President substitutes the President in case of its absence (Article 73 of the Macau Basic Law). The President shall exercise the following powers and functions:

- to preside over meetings

- to decide on the agenda, giving priority to government bills for inclusion in the agenda upon the request of the Chief Executive

- to decide on the dates of meetings

- to call special sessions during the recess period

- to call emergency sessions on his or her own or upon request of the Chief Executive

- to exercise other powers and functions as prescribed in the rules of the procedure of the Legislative Assembly

(Article 74 of the Macau Basic Law).

The Legislative Assembly members may introduce bills. Bills that do not relate to public expenditure or political structure or the operation of the Government may be introduced individually or jointly by members of the Assembly. The written consent of the Chief Executive shall be required before bills relating to Government policies are introduced (Article 75 of the Macau Basic Law). Members of the Legislative Assembly shall have the right to raise questions about the Government’s work in accordance with legal procedures (Article 76 of the Macau Basic Law). The quorum for the meeting shall be not less than one half of all its members. Except otherwise prescribed by the Basic Law, bills and motions shall be passed by more than half of all its members (Article 77 of the Macau Basic Law). A bill passed by the Legislative Assembly may take effect only after it is signed and promulgated by the Chief Executive (Article 78 of the Macau Basic Law).

5. Judiciary

The judicial power belongs to courts (Article 82 of the Macau Basic Law), independent from both the legislative and the executive powers (based on the principle of separation of powers, the cornerstone of any democratic system). Article 83 of the Basic Law establishes that the Macau Courts shall be subordinated to nothing but the law and shall not be subject to any kind of interference. Moreover, paragraph 1 of Article 7 of the Macau Civil Code states that “Courts and judges are independent and are only subject to the law.”

Macau has a three-tier court system composed by the First Instance Courts (Tribunais de Primeira Instância), the Second Instance Court (Tribunal de Segunda Instância), and the Last Instance Court (Tribunal de Última Instância). This last one, also named Court of Final Appeal, has the power of final adjudication (Article 84 of the Macau Basic Law), meaning that no appeals from Macau Courts are to be heard at the “Beijing Courts.” Judges shall be appointed by the Chief Executive on the recommendation of an independent commission composed of local judges, lawyers and renowned individuals. Judges shall be chosen on the basis of their professional qualifications. Qualified judges of foreign nationality may also be appointed. The President of the Last Instance Court shall be a Chinese citizen who is a permanent resident of the Region (Articles 87 and 88 of the Macau Basic Law). The judges of Macau shall exercise judicial power according to the law and shall be immune from legal action for discharging his or her judicial functions. During the term of office, a judge shall not concurrently assume other public or private posts, nor shall assume any post in organisations of a political nature (Article 89). Trial by jury is never used in practice.

An additional note in this context to mention that arbitration (arbitragem) has not been used frequently in Macau, with most of international businesses disputes linked with Macau being solved by the local courts. In May 2020 entered into force a new arbitration law (Law no. 19/2019) that combined in a single legal diploma the set of rules for international arbitration and the set of rules for domestic arbitration applicable to all arbitrations that take place in this Special Region of China. Despite still being based on the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration (1985), Law no. 19/2019 is applicable to both domestic and international arbitration.

5.1. Courts

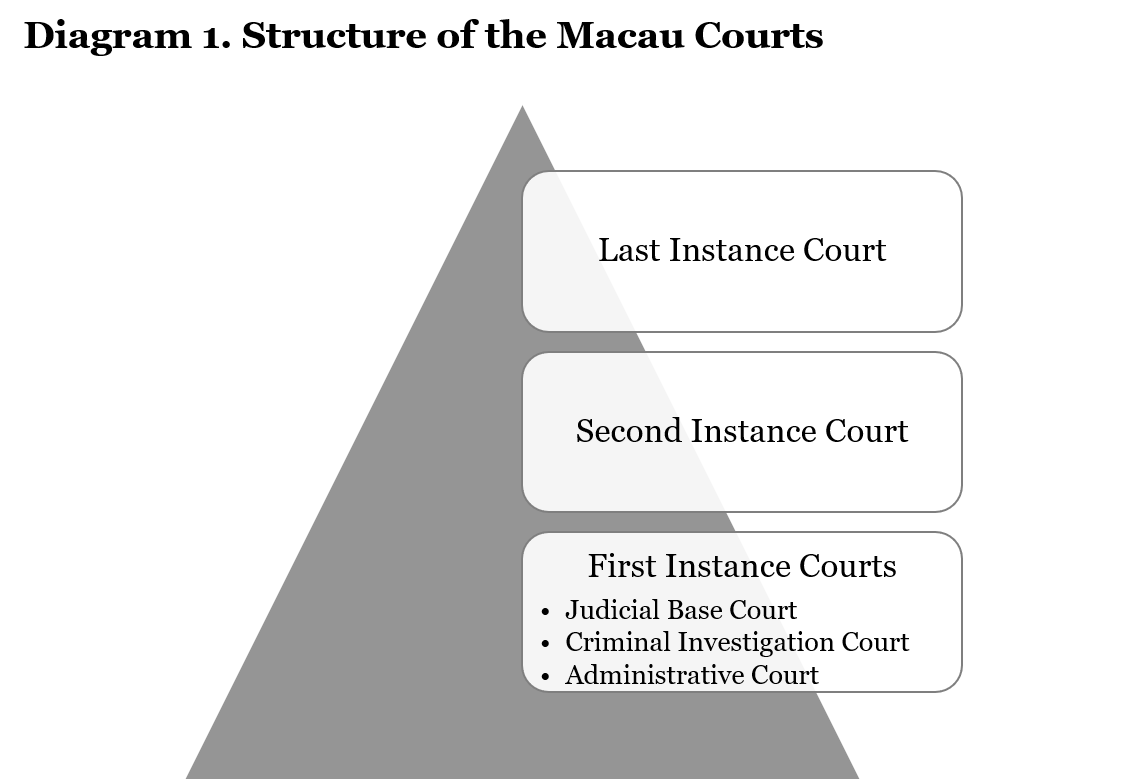

Per the Law of Judicial Organisation (Law no. 9/1999, last amended by Law no. 4/2019), the judicial system structure in Macau is organized as follows:  Diagram 1: Structure of the Macau Courts

Diagram 1: Structure of the Macau Courts

The Judicial Base Court and the Administrative Court are both First Instance Courts, where cases must be initiated. The Judicial Base Court (Tribunal Judicial de Base) is divided into a number of several specialized sections. The Judicial Base Court comprises sections with competence in relation to civil, criminal, small causes, labour, family, and minors’ disputes (Article 27 of Law no. 9/1999). Currently, there are a total of 32 judges on the Judicial Base Court. There is also the Criminal Investigation Court (Juízo de Instrução Criminal) with competence for criminal proceedings (Article 29 of Law no. 9/1999). Currently, this court is composed of three judges. The Administrative Court (Tribunal Administrativo) has jurisdiction over administrative, tax and customs duties cases (Article 30 of Law no. 9/1999). Currently, there is only one judge on the Administrative Court. The First Instance Courts may operate with a single judge or with a collegial panel. The President of the Courts of First Instance is currently Io Weng San.

The Second Instance Court decides appeals from the first levels courts, as well as voluntary arbitration proceedings that may be challenged according to the law. Moreover, it is also the court in which certain proceedings should be initiated. This means that it also judges at first instance as per paragraph 2 of Article 36 of Law no. 9/1999. Currently, it is composed of eight judges. The President of the Second Instance Court is now Tong Hio Fong.

The Last Instance Court is at the top of the court hierarchy and is composed of three judges. Besides deciding appeals from the Second Instance Court, it has the important function of the uniformization of Macau Court’s decisions. It is also the Court in which a very restricting number of proceedings should be initiated, such as legal actions against the Chief Executive due to exercise of his functions (Article 44 of Law no. 9/1999). Currently, it is composed of three judges. The President of the Court of Final Appeal is presently Sam Hou Fai.

5.2. Public Prosecutions Office

The Public Prosecutions Office (Ministério Público) is a separate body of magistrates whose main functions are to pursue criminal investigations and to initiate and ensure criminal proceedings as well as to represent the Special Region and public interests in general, protecting legitimate civil rights and interests and monitoring the application of the law (Article 56 of Law no. 9/1999). Article 90 of the Macau Basic Law establishes that these magistrates shall exercise prosecutorial functions as vested by law, independently and free from any interference. The Prosecutor General of the MSAR shall be a Chinese citizen who is a permanent resident of the Region, shall be nominated by the Chief Executive and appointed by the Central People’s Government. Procurators shall be nominated by the Procurator-General and appointed by the Chief Executive.  Diagram 2: Structure of the Macau Government

Diagram 2: Structure of the Macau Government

6. Sources of Law

6.1. Legislation

As Macau is a civil law or a Roman-German legal system of continental Europe tradition, the basis of its legal system are statutes that establish the general rules and principles applicable in the Special Region. Being the most important source of law, statutes are all codified. Legislation is general and abstract.

The most important Codes of Macau that were prepared during the so-called “Transition Period” (from 1988 until the transfer of sovereignty of Macau from Portugal to the PRC in 1999) are the following:

- the Civil Code, approved by Decree Law no. 39/99/M, of August 3 (last amended by Decree Law no. 48/99/M, of September 27)

- the Civil Procedure Code, approved by Decree Law no. 55/99/M, of October 8 (last amended by Law no. 4/2019)

- the Criminal Code, approved by Decree Law no. 58/95/M, of November 14 (last amended by Law no. 2/2016)

- the Criminal Procedure Code, approved by Decree Law no. 48/96/M, of September 2 (last amended by Law no. 10/2022)

- the Commercial Code, approved by Decree Law no. 40/99/M of August 3 (last amended by Law no. 4/2015)

This collection is globally also known as the “Five Codes”. Per Law no. 3/1999 (last amended by Law no. 20/2021) these codes, as well as all legislation in force in the MSAR, are available in the Macau Official Gazette (published weekly, on Monday and Wednesday, and organized in Series I and II) in Portuguese and Chinese.[4] The codes were all drafted originally in Portuguese and then translated into (traditional) Chinese.

The website of the Macau Official Gazette (Imprensa Oficial de Macau) has all legislation available for consultation free of charge. A complete unofficial English translation of the Commercial Code is also freely available at the website of the Official Gazette. An unofficial English translation of the Macau Basic Law is available at the website of WIPO – World Intellectual Property Organization, and a partial English translation of the Macau Civil Code is also available online, thanks to the work of Jorge A. F. Godinho, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Macau.

Laws are only compulsory after the publication in the Official Gazette of Macau (Article 4, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code). Per paragraph 2 of Article 4 of the Civil Code, “A period of time stated by each law shall elapse between the publication and the start of application of laws; in the absence of a stated period, laws shall start to apply on the sixth day subsequent to that of publication.” This time between the publication date of the law and its entry in force is called, in Latin, vacatio legis. According to the default rule stated, laws enter in force in the sixth day after the day of publication.

Ignorance or misinterpretation of the law does not justify the lack of compliance or exempt people from their respective sanctions (Article 5 of the Civil Code). As most laws are not temporary, they remain in force until they are revoked by another law. Paragraph 2 of Article 6 of the Civil Code states that “Revocation may arise from an express declaration, from incompatibility between the new provisions and the preceding rules, or from the circumstance that a new law regulates all matters covered by a preceding law.” In terms of interpretation of the law, Article 8, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code states that interpretation should not limit itself to the letter of the law, but reconstruct legislative thinking from the texts, considering, above all, the unity of the legal system, the circumstances in which the law was drafted and the specific conditions of the time in which it is applied. Per paragraph 1 of article 9 of the Civil Code, “cases that the law does not provide for are ruled according to the norm applicable to similar cases”, that is by analogy (analogia).

In respect to its application of laws in time, the general principle is that the law only provides for the future (Article 11, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code). And, even if retrospective effect is granted to the law, it shall be presumed that the effects already produced are not affected by the facts that the law intends to regulate (Article 11, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code).

It should be noted that national laws (from the PRC) shall not be applied in the MSAR, except for those listed in Annex III to the Macau Basic Law, which are, among others, the following:

- Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem, and National Flag of the PRC

- Resolution on the National Day of the PRC

- Nationality Law of the PRC

- Regulations of the PRC Concerning Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities

- Regulations of the PRC Concerning Consular Privileges and Immunities

- Law on the National Flag of the PRC

- Law on the National Emblem of the PRC

- Law of the PRC on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone

6.2. Customary Law and Equity

While laws are the immediate source of law, customary law also plays an important role in the Macau Jurisdiction. Per Article 2 of the Macau Civil Code (Legal value of usage), “Usage not contrary to the principles of good faith are legally admissible when the law so determines.”

In respect to equity, Article 3 of the Macau Civil Code establishes that “Courts can only decide in accordance with equity

- If there is such a legal provision

- If there is an agreement of the parties and the legal relation is not non-negotiable, or

- If the parties have previously agreed to resort to equity, under the terms applicable to arbitration clauses.”

6.3. Case Law

Case law also has a significant role in Macau. However, in contrast to the common law legal system, in which cases are the primary source of law, case law has only a secondary role in the Macau jurisdiction. Moreover, there is no system of binding precedent. While in common law legal systems, including Hong Kong, judicial decisions create new legal norms and the judges are obliged to respect prior decisions in accordance with the stare decisis principle, in the legal system of MSAR, case law serves mainly to interpret the law and only in rare cases create new law.

Despite the judicial precedents are not generally binding, they are quite relevant not only for overall understanding of the law and legal principles, but also because they work as a complement in judges’ reasoning whenever they must take their decisions. Paragraph 3 of Article 7 of the Macau Civil Code establishes that “In their decisions, courts shall take into account all cases deserving analogous treatment, in order to obtain uniform interpretation and application of the law.” It is also quite common to see in the lawyers’ arguments quotes from prior precedents, including Portuguese former decisions and decisions by local Courts in Macau.

Case law is available to public for information and research at the Government website of the Macau Courts (Tribunais de Macau).[5] Access to this database is free of charge. The judicial decisions are available either in Portuguese or Chinese or in both official languages of the Special Region. English and other languages are not used in Macau Courts, except in special situations in which translations are legally required.

6.4. Doctrinal Work

The doctrinal work by academics is also influential, especially the Portuguese legal bibliography. It may serve as an instrument to interpret the law when it is not clear. Hence, it is considered a “non-material” source of law.

To conclude this part, in respect to the hierarchy of norms, the “constitution” (the Macau Basic Law), is the norm of the norms followed by the legal rules enacted by the Legislative Assembly, the “parliament” in Macau. Although laws are an immediate source of law, international agreements applicable in Macau shall prevail over ordinary laws. After these ones, and depending on the legal system, may come the judicial decisions, when the law admits the principle of stare decisis. Nevertheless, as mentioned, in Macau, as a rule, judicial decisions are used mainly to interpret the law. Moreover, as referred to above, legal costumes are also a source of law. Doctrine, in the end of the list, is not really a source of law, as it serves merely to help with the interpretation of the law.

7. Legal Education and Professional Organizations

The University of Macau (Universidade de Macau, also referred to as “UM”) is a public university founded in 1991. It substituted the former University of East Asia (first established in 1981). The Faculty of Law of the UM is the oldest law school in the Region. It offers bachelor’s, postgraduate, and Master of Law programs in Chinese and Portuguese, as well as a master and postgraduate of law programme in European Union Law, International Law, and Comparative Law and a master and postgraduate programme in International Business Law both in English language. The Faculty of Law also offers a doctoral programme (PhD) in law, in Chinese, Portuguese, and English. The University has now a new campus located in Hengqin Island, next to Macau, but in mainland China territory. It is however under Macau’s jurisdiction (see campus news).

The Institute of European Studies of Macau (Instituto de Estudos Europeus de Macau) is a private organization established in 1995 that also offers some legal advanced programs, such as the Master of Social Sciences in European Studies. This master is offered in cooperation with the University of Macau, and it is a two-year interdisciplinary programme that gives in-depth insights into the European Union’s past, present and future from different perspectives. The institute is comprised by the Pearl River Delta Academy of International Trade and Investment Law and the Intellectual Property Law School. The institute’s main purpose consists in functioning as a bridge between the European Union and the Asia-Pacific Region.

Graduates in law who intend to practice law as lawyers and act on behalf of clients before a Court of law must be duly registered at the Macau Lawyers Association (Associação de Advogados de Macau, also referred to as AAM), a public and autonomous entity that offers training programs for lawyers, including the Intensive Adaptation Course to the Macau Law. In Macau, as in Portugal, there is no difference between barristers and solicitors. To find a lawyer practicing in Macau, the AAM provides a directory link, where one can look for lawyers, trainees, and officers.

The Legal and Judicial Training Center (Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária) of Macau oversees the training program for the judges and public prosecutors’ magistrates. The Center also provides short intensive legal courses and lectures for public servants of the MSAR.

Rui Cunha Foundation (Fundação Rui Cunha) is a non-profit organization that supports the Centre for Reflection, Study and Dissemination of Macau Law (Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, also referred to as CREDDM), where those interested may participate in conferences and seminars related to current issues of concern and relevance to the legal practice. As an independent organic unit of the Rui Cunha Foundation, established in 2012, the CREDDM has as its main mandate the coordination of all resources allocated to the investigation of Macau Law within its uniqueness, to contribute to the creation, preservation, and dissemination of doctrine and jurisprudence of the Special Region.

Moreover, the Macau Foundation established in 2001 is a legal person governed by public law that aims to promote, develop and study activities of a cultural, social, economic, educational, scientific, academic and philanthropic nature, including activities aimed at promoting the Special Region. Its website offers news and publications of, among others, legal interest.

8. Health System

After the handover to the PRC, the public health care system in Macau has been governed under the aforementioned “one country, two systems” principle, with International Health Regulations from the World Health Organization being applicable directly to the Special Region. The Macau Health Bureau (Serviços de Saúde) provides hospital care and primary healthcare to all citizens and is in charge of the implementation of all actions necessary to health promotion and disease prevention in the Region.

Decree Law no. 24/86/M of March 15, under the principle of gratuity, establishes that health services provided by the government are fully or partially funded by the General Budget (Article 3). Thus, all Macau residents are entitled to free services at health care centers and at the public hospitals. The public health system is mainly funded by the Macau Government, which means that it provides primary healthcare and hospital services to all legal residents of the Region free of charge (subject to some statutory requirements), including medication.

Besides the public general hospital Conde São Januário (Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário, also referred to as CHCSJ) opened in 1874 in Macau Peninsula, which offers 24-hour emergency care and provides a wide variety of outpatient care, there are several public health centres located in different areas across the Region that provide primary public healthcare outpatient services. The University Hospital of Science and Technology (Universidade de Ciência e Tecnologia de Macau, also referred to as M.U.S.T. hospital) is a university hospital located in Taipa that provides inpatient care and outpatient services. In addition, there is a non-governmental hospital operating in the Special Region, the Kiang Wu Hospital, subsidized by the Government, that offers a variety of medical services, such as inpatient care, outpatient care, specialist treatment, and 24-hour emergency services. There are also many small private clinics and laboratories in the Region.

9. Useful Links, Portals, and Databases

Major open access sources of legal information:

- at the Official Gazette (Jornal Oficial) it is possible to find all legislation in force, as well as diplomas that were revoked

- at the Government’s GOV.MO (Portal do Governo da RAE de Macau) it is available a list of links (in English) of all relevant Government departments and agencies in Macau

- At the Macau Courts (Tribunais de Macau) database it is possible to access to all relevant case law of the Region

- law Firms, lawyers and trainee lawyers in the Region can be found in the directory available at the Macau Lawyers Association (Associação de Advogados de Macau)

The laws published in the Official Gazette of Macau are, as a rule, published in Portuguese and Chinese, both official languages. Exceptionally, it is possible to find English versions of some diplomas, such as the Commercial Code (although, as mentioned above, it is an unofficial translation).

Generally, the Government departments’ webpages are written in Portuguese and Chinese. Some offer a webpage in English or with partial information written in English, such as

- the Monetary Authority (Autoridade Monetária), which is, among others, in charge of advising and assisting the Chief Executive in formulating and applying monetary, financing, exchange rate and insurance policies, as well as monitoring the stability of the financial system

- the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau (Direcção de Inspecção e Coordenação de Jogos), which provides guidance and assistance to the Chief Executive on the definition and execution of the economic policies for the operations of the casino games of fortune or other ways of gaming and gaming activities offered to the public

- the Economic Services Bureau (Direcção dos Serviços de Economia), which assists the Government in the study, formulation and implementation of economic policy in the areas of economic activity and intellectual property, as well as in other responsible areas stipulated by law (it has unofficial English versions, of the Industrial Property Code and the Regime of Copyright and Related Rights).

Other open access sources include:

- the IP Database for Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macao SAR offers information (in Chinese and in English) in respect to Intellectual Property of Macau, but also includes other jurisdictions

- the Library of the University of Macau (Wu Yee Sun Library) offers access to a database of law and legislation in Portuguese, Chinese, and English

- the Statistics Bureau (Direcção dos Serviços de Estatística e Censos) provides access to a database about Macau demographic, social, economic, and environmental aspects in Portuguese, Chinese, and English

- the Data Protection Bureau (Gabinete para a Protecção de Dados Pessoais) has a database available in Portuguese, Chinese, and English

- the Macau Post and Telecommunications (Direcção dos Serviços de Correios e Telecomunicações) provides useful information in Portuguese, Chinese, and English

- the Public Administration and Civil Service Bureau (Direcção dos Serviços de Administração e Função Pública) offers information on public law and administrative/government/public servants’ careers, available in Portuguese and Chinese.

10. Bibliography and Other Sources

Most legal publications written by legal professionals is either in Portuguese or in Chinese. The following is a list of relevant legal books written by Portuguese authors in reversed chronological order. 2022

- Silva, Paula Costa; Figueiredo, José Miguel, “Lei da Arbitragem de Macau Anotada Vol. I – Edição Bilingue Português – Chinês (Artigo 1.º a 45.º)” Associação de Advogados de Macau, AAFDL Editora, 2022.

2021

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de, “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro II, Volume X,” (Artigos 779.º a 864.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2021.

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de, “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro II, Volume IX,” (Artigos 682.º a 778.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2021.

- Silva, António Correia Marques da, “Curso Sobro O Procedimento Disciplinar de Macau (Teoria e Prática),” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2021.

- Santos, Hugo Luz dos Santos; Figueiredo, José Miguel, “Regime Jurídico da Concessão de Crédito para Jogo ou para Aposta em Casino, Anotado e Comentado”, AAFDL, Lisboa, 2021.

2020

- Henriques, Manuel Leal, “Direito Disciplinar de Macau,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020.

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de, “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro Ⅱ, Volume Ⅷ,” (Artigos 545.º a 681.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020.

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de, “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro II, Volume VII,” (Artigos 477.º a 544.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020.

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro II, Volume VI, ” (Artigos 391.º a 476.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020.

2019

- Godinho, Jorge A. F., “Os Casinos de Macau – História do Maior Mercado de Jogos de Fortuna ou Azar do Mundo,” Almedina, Coimbra, 2019

- Henriques, Manuel Leal, “Direito Penal de Macau,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2019.

- Oliveria, Fernanda Paula Marques de, “Manual de Direito do Urbanismo,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2019.

- Robalo, Teresa Lancry G. Albuquerque e Sousa, “Colectânea de Direito Penal de Macau,” Materiais de Apoio, Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2. edição, 2019.

2018

- Oliveira, João Gil de; Pinho, José Cândido de, “Código Civil de Macau Anotado e Comentado, Jurisprudência, Livro I, Volume I,” (Artigo 1.º a 66.º), Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2018.

- Pinho, José Cândido de, “Notas e Comentários ao Código de Processo Administrativo Contencioso, Volume II,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2018.

2017

- Cardinal, Paulo, “Direito, Transição e Continuidade – Escritos Dispersos de Direito Público de Macau,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2017.

- Man Teng Iong, “Diretivas Antecipadas de Vontade, Um Regime Existente em Macau?,” Novas Edições Acadêmicas, 2017.

2016

- Godinho, Jorge A. F., “Direito do Jogo – Volume I,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2016.

- Sena, Pedro Pereira; Figueiredo, José Miguel “Estudos Comemorativos dos XX Anos do Código Penal e do Código de Processo Penal de Macau,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2016.

- Torrão, João António Valente, “Regime Jurídico Contratação Pública da RAEM,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2016.

2015

- Cardinal, Paulo, “Estudos de Direitos Fundamentais: No Contexto da Jusmacau,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2015.

- Figueiredo, José Miguel; Abrantes, António Manuel “Manual de Legística Formal,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2015.

- Lima, Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de; Dantas, Álvaro António Mangas Abreu, “Código de Processo Administrativo Contencioso Anotado,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2015.

- Pires, Cândida da Silva Antunes, “Lições de Processo Civil de Macau,” Almedina, Coleção UM, 2015.

- Vitória, Fernando ; Madureira, Óscar, “Direito do Jogo em Macau – Evolução, História e Legislação,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2015.

2014

- Guedes, João Vieira, “Da Questão Do Erro Médico Em Responsabilidade Civil – Uma Abordagem,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2014.

- Pires, Cândida da Silva Antunes, “Direito de Macau – Reflexões e Estudos,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2014.

2013

- Correia, Paula Nunes, “Regime Jurídico do Erro Negocial em Macau,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2013.

2012

- Quental, Miguel Pacheco Arruda, “Manual de Formação de Direito do Trabalho em Macau,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2012.

2010

- Pires, Cândida da Silva Antunes e; Dantas, Álvaro António Mangas Abreu, “Justiça Arbitral em Macau – A Arbitragem Voluntária Interna,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2010.

2006

- Dias, José Eduardo Figueiredo, “Manual de Formação de Direito Administrativo de Macau,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2006.

2005

- Henriques, Manuel Leal, “Manual de Direito Disciplinar,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2005.

- Henriques, Manuel Leal, “Manual de Formação de Direito Penal de Macau,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2005.

- Lima, Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de, “Manual de Direito Processual Civil,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2005.

There are a few periodical publications for sale at CRED-DM Your digital bookstore by Rui Cunha Foundation, law magazines (Doctrine, Jurisprudence and Legislation commented), written by legal professionals residing in Macau:

- Legisiuris Macau

- Pensar Direito

- Cadernos CRED-DM:

- Monteiro, Vicente, “Cadernos CRED-DM Direito Registral – Registos Predial e Comercial,” 2013.

- Redinha, Pedro, “Cadernos CRED-DM – Processo Penal e a Prática Judiciária na RAEM,” 2014.

- Torrão, João António Valente, “Cadernos CRED-DM Regime Jurídico das Infrações Administrativas e Tributárias na RAEM,” 2015.

The Centre for Law Studies of the Faculty of Law (of the UM), performs an important role in the translation of documents, preparation of articles and in publication of juridical papers. See a list of Published Works by the Centre for Law Studies and also the Macau Law Review (journal). Also see the Journal/Newsletter of the UM: Boletim da Faculdade de Direito . Moreover, see the Journal of the Macau Studies from Centre for Macau Studies. The Public Administration and Civil Service Bureau has available online for research a magazine named Revista de Administração Pública de Macau. The Research Centre of the Macao Polytechnic Institute has an academic journal named “One Country Two Systems Studies” and organizes conferences, forums and seminars. The following is a list of legal literature written in Chinese or Chinese translations from works written by Portuguese authors in reversed chronological order.[6] 2022

- 法律及司法培訓文集 第十二册,2022年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Formação Jurídica e Judiciária-Colectânea, Tomo XII,” Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2022).

- 澳門刑法典註釋及評述-第三冊,作者:Manuel Leal-Henriques,2022年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Anotação e Comentário ao Código Penal de Macau, Volume III,” Manuel Leal-Henriques, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2022).

2021

- 親屬法及未成年人法研究中文原文版 (第一次加印),統籌:尹思哲,2021年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Estudos de Direito da Família e Menores Textos Originais em Língua Chinesa 1.ª Reimpressão,” Coordenador Manuel Marcelino Escovar Trigo, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2021).

2020

- 澳門民事訴訟法典註釋與評論-第二冊 (中文版),作者:李淑華 及 利馬,中文譯者:鄧志強,2020年7月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Código de Processo Civil de Macau, Anotado e Comentado,” Volume II, Cândida da Silva Antunes Pires and Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de Lima, translation from Tang Chi Keong, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020).

- 《澳門刑事訴訟法教程》下冊 (第三版 – 修正及更新) 中文版,作者:Manuel Leal-Henriques,中文譯者:盧映霞,2020年7月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Manual de Formação de Direito Processual Penal de Macau,” Volume II (3rd edition), Manuel Leal-Henriques, translation from Lou Ieng Ha, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2020).

- 行政法教程 (第二卷) – 中文版,作者:迪奧戈•弗雷斯•亞瑪勒,中文譯者:黃顯輝 / 黃淑禧 / 黃景禧,2020年出版,社會科學文獻出版社 (“Curso de Direito Administrativo,” Volume II, Diogo Freitas do Amaral, translation from Vong Hin Fai, Vong Sok Hei and Vong Keng Hei, Social Science Academic Press, 2020).

2019

- 澳門民事訴訟法典註釋與評論-第一冊 (中文版),作者:李淑華 及 利馬,中文譯者:鄧志強,2019年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Anotação e Comentário ao Código do Processo Civil de Macau,” Volume I, Cândida de Silva Antunes Pires and Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de Lima, translation from Tang Chi Keong, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2019).

- 澳門刑法典註釋及評述 — 第二冊 (中文版),作者:Manuel Leal-Henriques,中文譯者:盧映霞及陳曉疇,2019年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Anotação e Comentário ao Código Penal de Macau,” Volume II, Manuel Leal-Henriques, translation from Lou Ieng Ha and Chan Io Chao, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2019).

- 刑事訴訟法 – 中文版,作者:喬治•德•菲格雷多•迪亞士,中文譯者:馬哲 / 繳洁,2019年出版,社會科學文獻出版社 (“Direito Processual Penal,” Jorge de Figueiredo Dias, translation from Ma Zhe and Jiao Jie, Social Science Academic Press, 2019).

2017

- 商法教程 (第一卷) – 中文版,作者:喬治•曼努埃爾•高迪紐德•阿布萊鳥,中文譯者:王薇,2017年出版,法律出版社 (“Curso de Direito Comercial,” Jorge Manuel Coutinho de Abreu, translation from Wang Wei, Law Press China, 2017).

2015

- 澳門特別行政區基本法中基本權利的制度,作者:José Melo Alexandrino,中文譯者:劉耀強,2015年7月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“O Sistema de Direitos Fundamentais na Lei Básica da Região Administrativa Especial de Macau,” José Melo Alexandrino, translation from Lau Io Keong, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2015).

- 行政訴訟法培訓教程,作者:簡德道,中文譯者:何偉寧,2015年2月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Manual de Formação de Direito Processual Administrativo Contencioso,” José Cândido de Pinho, translation from Ho Wai Neng, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2015).

2014

- 刑法(中文版),作者:Jorge de Figueiredo Dias(迪亞斯),中文譯者:陳軒志、何志遠、關冠雄、歐陽傑、譚嘉華、沈偉強,2014年出版 (“Textos de Direito Penal,” Jorge de Figueiredo Dias, translation from Chan Hin Chi, Ho Chi Un, Kuan Kun Hong, Ou Ieng Chie, Tam Ka Wa and Sam Wai Keong, 2014).

- 澳門行政處罰法教程,作者:何志遠,2014年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Manual do Direito Administrativo Sancionatório de Macau,” Ho Chi Un, Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2014).

2013

- 行政訴訟散論,作者:米萬英,2013年8月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Estudos Diversos Sobre Contencioso Administrativo,” Mai Man Ieng, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2013).

2012

- 民事訴訟法教程 — 第二版譯本,作者:Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de Lima,中文譯者:葉迅生、盧映霞,2012年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Manual de Direito Processual Civil,” 2nd edition, Viriato Manuel Pinheiro de Lima, translation from Ip Son Sang and Lou Ieng Ha, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2012).

- 澳門仲裁公正—內部自願仲裁,作者:Cândida da Silva Antunes Pires, Álvaro António Mangas Abreu Dantas,中文譯者:葉迅生,2012年12月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Justiça Arbitral em Macau – A Arbitragem Voluntária Interna,” Cândida da Silva Antunes Pires and Álvaro António Mangas Abreu Dantas, translation from Ip Son Sang, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2012).

2010

- 法律及正當論題導論(中文版)(第3版),作者:J. Baptista Machado(馬沙度),中文譯者:黃清薇及杜慧芳,2010年出版 (“Introdução ao Direito e ao Discurso Legitimador,” 3rd edition, J. Baptista Machado, translation from Wang Quin Wei and Tou Wai Fong, 2010).

- 民法總論(中文版)(第2版),作者:Orlando de Carvalho(加華尤),中文譯者:黃顯輝,2010年出版 (“Teoria Geral do Direito Civil,” 2nd edition, Orlando de Carvalho, translation from Vong Hin Fai, 2010).

- 《澳門刑事訴訟法教程》上冊 (第二版) – 中文版,作者:Manuel Leal-Henriques,中文譯者:盧映霞、梁鳳明,2010年6月出版,法律及司法培訓中心 (“Manual de Formação de Direito Processual Penal de Macau,” Volume I (2nd edition), Manuel Leal-Henriques, translation from Lou Ieng Ha and Leong Fong Meng, Centro de Formação Jurídica e Judiciária, 2010).

2009

- 行政法教程(中文版)(第一卷),作者:Diogo Freitas do Amaral,

中文譯者:黃顯輝及王西安,2009年出版 (“Curso de Direito Administrativo,” Volume I, Diogo Freitas do Amaral, translation from Vong Hin Fai and Wang Xian, 2009). Some authors have published in English. The following is a bibliography of selective basic legal works in English in reversed chronological order. 2023

- Raposo, Vera Lúcia; Iong, Man Teng, “Advance Directive in Macao: Not Legally Recognised, but…,” in D. Cheung & M. Dunn (Eds.), Advance Directives Across Asia: A Comparative Socio-legal Analysis (pp. 262-275), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

2022

- Coelho, Carlos Eduardo; Proença, Rui Pinto, “Gaming Law 2022,” Law and Practice, Chambers and Partners, 2022.

2021

- Guerreiro, Daniela; Leitão, José, “Consumer Protection in Macau: What changed?,” LexisNexis Hong Kong, 2021.

2020

- Câmara, Paulo; Leitão José, “OPINION-The Case for a Macau stock exchange: An opportunity in challenging times,” Macau News Agency, 2020Iong, Man Teng, “Artificial Intelligence and Traditional Chinese Medicine in Portuguese Criminal Law,” Tec Yearbook – Artificial Intelligence & Robots (School of Law of the University of Minho), pp. 39-51, 2020 Iong, Man Teng, “Telemedicine in China: An Enlightenment from COVID-19,” Medicine and Law, 39(4): 595-602, December 2020.

- Iong, Man Teng, “Criminal Liability for Violation of Informed Consent in Macao,” UMagazine (University of Macau), Issue 22: 62-65, Spring/Summer 2020.

- Raposo, Vera Lúcia; Iong, Man Teng, “The struggle against the CoViD-19 pandemic in Macao,” BioLaw Journal, NO 1S(2020): 747-752, 2020.

2019

- Raposo, Vera Lúcia, “Informed Consent in China and Macao,” in Informed Consent and Health – A Global Analysis (Thierry Vansweevelt and Nicola Glover-Thomas eds.), Edward Arnold Publishers, 2019, pp. 144-162.

- Iong, Man Teng, “Please Allow True Self-Decision Under Macao Law,” Medicine and Law, 38(2): 183-192, June 2019.

2018

- Raposo, Vera Lúcia, “Macao Report: Informed Consent in a Multilingual and Multicultural Country, a Bioethical Challenge,” The Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics (SSCI), 27(3), 2018, pp. 385-396.

- Iong, Man Teng, “Fight between Secret of Traditional Chinese Medicine Prescriptions and Duty to Inform,” Medicine and Law, 37(1): 229-243, March 2018.

2016

- Leandro, Francisco José B. S., “Macau SAR and the European Union – Two subjects of International Law?,” Centro de Reflexão, Estudo e Difusão do Direito de Macau, 2016.

- Santos, Hugo Luz, “Gaming Legal Framework in Macau SAR: An overview,” Lambert, 2016.

2012

- Dias, José Eduardo Figueiredo, “Administrative Law of Macau Handbook,” LexisNexis, Hong Kong, 2012.

- Jianhong Fan; Yuan Zhao; Lao Lo Keong, “Corporations and Partnerships in Macau,” Kluwer Law International, 2012.

- Mancuso, Salvatore, “Studies on Macau Gaming Law,” Universidade de Macau, LexisNexis, Hong Kong, 2012.

2011

- Godinho, Jorge A. F., “Studies on Macau Civil, Commercial, Constitutional and Criminal Law,” Universidade de Macau, LexisNexis, Hong Kong, 2011.

2009

- Cardinal, Paulo, “The Judicial Guarantees of Fundamental Rights in the Macau Legal System: A Parcours Under the Focus of Continuity and of Autonomy,” One Country, Two Systems, Three Legal Orders – Perspectives of Evolution, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009, pp 221–269.

2007

- Godinho, Jorge A. F., “Macau Business Law and Legal System,” LexisNexis, Hong Kong, 2007.

2004

- Pereira, Alexandre Dias, “Business Law: A Code Study – The Commercial Code of Macau,” Almedina, 2004.

[1] This is an unofficial English version.

[2] This Joint Declaration defined the process by which Macau would return to Chinese sovereignty as a Special Administrative Region.

[3] See The New York Times: “Stanley Ho, Who Turned Macau Into a Global Gambling Hub, Dies at 98.”

[4] Legislation includes Laws, Decree Laws (approved/published before the transfer of sovereignty in 1999 and that remain in force), Administrative Regulations and Chief Executive Orders and Dispatches.

[5] The website is only available in Portuguese and in Chinese.

[6] The author would like to thank his colleague and friend, Man Teng IONG from Macau, who has kindly provided an invaluable cooperation in preparing this portion of the article.