An Introduction to the Law of the Southern African Development Community

By Dr. Frederik Cowell

Dr Frederick Cowell is a Senior Lecturer in Law at Birkbeck College, University of London. He specializes in Public International Law and was previously a legal advisor for human rights NGOs.

Published July/August 2023

(Previously updated by Dunia Zongwe in July/August 2014)

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1. Historical Background

- 1.2. Economy

- 1.2.1. Outlook

- 1.2.2. Progress Towards Regional Economic Integration

- 2. SADC Law

- 2.1. Overview

- 2.2. Principles

- 3. The Constitution

- 4. Areas of SADC Law

- 4.1. Trade and Industry

- 4.1.1. The Trade Protocol

- 4.1.2. Trade in Goods

- 4.1.2.1. Removal of Trade Barriers

- 4.1.2.2. Customs Procedures

- 4.1.3. Trade Measures

- 4.1.3.1. Exceptions

- 4.1.3.2. Standards-Related Measures

- 4.1.3.3. Safeguard Measures

- 4.1.3.4. Dumping and Subsidies

- 4.1.4. Services, Intellectual Property and Competition

- 4.1.5. Intra-Regional Trade and Trade with Third Parties

- 4.1.6. Committees, Units, and the Forum

- 4.2. Finance and Investment

- 4.2.1. The Overall Picture

- 4.2.2. The Legal Landscape

- 4.2.3. The Finance Protocol

- 4.2.4. Investment Cooperation

- 4.2.4.1. Promotion

- 4.2.4.2.Regulation and Protection

- 4.2.5. Central Banking and Financial Markets

- 4.2.5.1. Central Banking

- 4.2.5.2.Financial Markets

- 4.3. Mining

- 4.1. Trade and Industry

- 5. Member States

- 5.1. Angola

- 5.2. Botswana

- 5.3. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

- 5.4. Eswatini

- 5.5. Lesotho

- 5.6. Madagascar

- 5.7. Malawi

- 5.8. Mauritius

- 5.9. Mozambique

- 5.10. Namibia

- 5.11. Seychelles

- 5.12. South Africa

- 5.13. Tanzania

- 5.14. Zambia

- 5.15. Zimbabwe

- 6. Main Institutions

- 6.1. The Summit

- 6.2. The Council and the Standing Committee

- 6.3. The Secretariat

- 7. Dispute Settlement and the Tribunal

- 7.1. The Panel Procedure

- 7.2. The Tribunal

- 7.2.1. Composition

- 7.2.2. Jurisdiction

- 7.2.3. Trade Disputes

- 7.3. The Tribunal in the Campbell Case

- 7.3.1. Campbell v. Zimbabwe

- 7.3.2. Suspension of the Tribunal

- 8. Resources

- 8.1. Publications

- 8.2. Online Resources

1. Introduction

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is a regional economic community composed of 15 countries in Southern Africa (member states), namely Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. SADC is thus in theory an arrangement that reduces or rules out trade barriers between member states while leaving in place barriers against imports from outside regions. The market and population size of SADC is estimated at 289 million. The official languages of SADC are English, French, and Portuguese.

1.1 Historical Background

1.1.1. The Coordinating Conference 1980-1992

The Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) is the ancestor of the present-day SADC. Nine countries in Southern Africa founded the SADCC in Lusaka (Zambia) on April 1, 1980, by adopting the ‘Lusaka Declaration – Southern Africa: Towards Economic Liberation – A Declaration by the Governments of Independent States of Southern Africa.’ The nine SADCC majority-ruled founding countries were Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland (now Eswatini), Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In 1977, representatives of the Frontline States engaged in consultations. ‘Frontline States’ was the name given to the group of Southern African states (i.e., Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia) that set out to bring about Black majority rule in South Africa. In May 1979, in Gaborone (Botswana), foreign affairs ministers of the Frontline States met and agreed that ministers responsible for the economy in the Frontline States should convene a meeting, which they did two months later in Arusha (Tanzania). The Arusha meeting that took place the following year on April 1, 1980, in Lusaka (Zambia) paved the way for the birth of SADC. The Frontline States movement ceased operations following the advent of democratization in South Africa in 1994.

The initial purpose of the SADCC was twofold: To coordinate development projects to promote collective self-reliance by shaking off the economic dependence of SADCC members on apartheid and white minority-ruled South Africa as well as other countries, and to implement projects with national and regional impact. Stated differently, SADCC was originally conceived as the economic arm of the struggle for the liberation of Southern Africa from colonial and white minority rule, and not as the key instrument of regional economic integration that it later became.

1.1.2. The Community 1992-Present

Member states turned SADCC into SADC in 1992 in Windhoek, Namibia, and adopted the Windhoek Declaration and the Treaty establishing SADC. The meeting in Windhoek elevated the basis of cooperation among member states from a loose association to a legally binding agreement.[1] The express purpose of the transformation from SADCC to SADC was to deepen economic cooperation and integration to undo the factors that stop member states from sustaining economic growth and socio-economic development.[2] The small size of individual markets, inadequate infrastructure the cost of providing this infrastructure, and low income made it difficult for member states individually to bring in investments necessary for sustained growth.[3]

Prompted by concerns for greater coherence and better coordination, member states overhauled SADC in March 2001 at an extraordinary meeting Summit in Windhoek. Important decisions at that meeting include the classification of the 21 sectors of SADC into four clusters under four directorates of the SADC Secretariat, and the establishment of SADC national committees to articulate their respective individual member state interests concerning SADC. The Summit also approved the preparation by the Secretariat of a Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan. Another decision was to institutionalize—for the first time since the end of the Frontline States movement—security and political cooperation in the Organ on Politics, Defense, and Security (Defense Organ). In that sense, the Defense Organ is the descendant of the Frontline States.

1.1.3. The Free Trade Area and Customs Union 2000-present

The Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP) (see also Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan 2020-2030), SADC’s regional integration policy framework, plans for SADC to form a free trade area by 2008 and a customs union by 2010. The formation of a free trade area dates to 2000. Member states began to join the SADC Free Trade Area gradually. The first to join the area were the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) members, which are Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, and South Africa. Madagascar, Mauritius, and Zimbabwe then fell in the free trade area. In 2008, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia formally integrated the free trade area. Only Angola, the DRC, and Seychelles have not yet joined the free trade area, although it is anticipated they will do so over time.

In October 2008, a Tripartite Summit of Heads of State or Government from SADC, the East African Community (EAC), and the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) agreed in Kampala, Uganda to set up the African Free Trade Zone, a free trade zone with EAC and COMESA. To complement the SADC free trade area, the Summit deliberated in August 2013 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania on the formation of a customs union in SADC. In 2010, an attempt was made by SADC to form a customs union, but the decision to form a customs union was eventually postponed. This has remained the case for nearly a decade, and despite a commitment to have a customs union by 2013, there was no progress towards one by 2022.

The SADC Protocol on Trade (2005) envisaged a Free Trade Area in the SADC Region and in 2008 SADC announced that 85% of intra-regional trade among states in the SADC Free Trade Area was tariff-free.[4] There have, however, been some problems with individual countries maintaining their tariff-free access, particularly in certain industrial sectors.

1.2. Economy

1.2.1. Outlook

Of all the regional economic communities, the economy of SADC is the largest. It comprises roughly 289 million people, speaking English, French, and Portuguese as one of their official languages. Most member states forged and maintained various strong political, historical, and cultural ties. The region also comprises 15 heterogeneous states, at different stages of development, though mostly underdeveloped; still two-thirds of SADC economies consist of middle-income countries.

Table 1: SADC Member States by Income Levels

| Rank | SADC country | Income level |

Income bracket (Income per Capita in US Dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seychelles | Upper-middle income | Between 4,086 and 12,615 |

| 2 | Botswana | ||

| 3 | Mauritius | ||

| 4 | South Africa | ||

| 5 | Namibia | ||

| 6 | Angola | ||

| 7 | Eswatini | Lower-middle income | Between 1,036 and 4,085 |

| 8 | Lesotho | ||

| 9 | Zambia | ||

| 10 | Tanzania | Low income | Between 1,035 and 0,0 |

| 11 | Mozambique | ||

| 12 | Madagascar | ||

| 13 | Malawi | ||

| 14 | Zimbabwe | ||

| 15 | Dem. Rep. Congo |

Source: World Bank (2014); Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook (2013).

The national economies exhibit different growth rates, reflecting different resource endowments and economic sizes (See Table 3 below). The gross domestic product (GDP) of SADC, the largest regional economic community by GDP and gross income in Africa, was over 767 billion US dollars in 2014, which placed the economy of the SADC region above the Saudi Arabian economy but below that of the Netherlands. Thus, the SADC economy is the 19th in the world.

Table 2: Size of SADC economy

| No. | SADC country |

GDP (in Billion US Dollars) |

Rank in Africa (Out of 54 Countries) |

World Rank (out of 187 Countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 419.02 | 1 | 29 |

| 2 | Angola | 67.40 | 5 | 60 |

| 3 | Tanzania | 67.84 | 13 | 92 |

| 4 | Zambia | 22.15 | 17 | 103 |

| 5 | Dem. Rep. Congo | 95.89 | 19 | 108 |

| 6 | Botswana | 21 | 115 | |

| 7 | Mozambique | 17,474 | 22 | 116 |

| 8 | Namibia | 14,211 | 25 | 121 |

| 9 | Mauritius | 12,403 | 27 | 124 |

| 10 | Zimbabwe | 12,054 | 31 | 130 |

| 11 | Madagascar | 12,032 | 32 | 132 |

| 12 | Malawi | 6,342 | 37 | 150 |

| 13 | Eswatini | 3,888 | 41 | 155 |

| 14 | Lesotho | 2,951 | 44 | 159 |

| 15 | Seychelles | 1,036 | 49 | 170 |

| Total | 767,489 | |||

Source: International Monetary Fund.

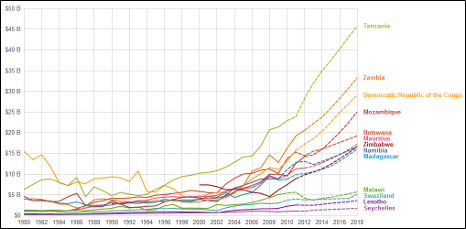

Figure 1: GDPs in SADC (except for Angola and South Africa)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook (October 2013).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that the SADC economy will reach 868 billion US dollars in 2018 from 767 billion US dollars in 2014 (see Table 3 below), that is, an increase of about 11%. It also estimates that during those four years, a few changes will occur in the relative economic size of some member states. Mozambique will overtake Botswana while the Namibian economy will be surpassed by that of Mauritius and Zimbabwe. Malawi will be the only economy in the region experiencing a decline (see Figure 1, Table 2, and Table 3).

Table 3: The projected size of the SADC economy (2018)

| No. | SADC country |

GDP (in Million US dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 464,285 |

| 2 | Angola | 169,153 |

| 3 | Tanzania | 45,767 |

| 4 | Zambia | 33,296 |

| 5 | Dem. Rep. Congo | 29,108 |

| 6 | Mozambique | 25,040 |

| 7 | Botswana | 19,231 |

| 8 | Mauritius | 17,161 |

| 9 | Zimbabwe | 16,630 |

| 10 | Namibia | 16,603 |

| 11 | Madagascar | 16,052 |

| 12 | Malawi | 5,708 |

| 13 | Eswatini | 5,089 |

| 14 | Lesotho | 3,591 |

| 15 | Seychelles | 1,725 |

| Total | 868,439 | |

Source: International Monetary Fund.

SADC is predominantly an exporter of primary commodities. Ninety percent of SADC exports consist of mineral and agricultural commodities. SADC exports about 53% of vanadium, 49% of platinum, 40% of chromite, 36% of gold, 50.1% of diamonds, and 20% of cobalt.[5] SADC member states depend on these exports for foreign exchange earnings, investment, and wealth creation. On the other hand, SADC mainly imports capital and intermediate goods, which only South Africa and, to a much lower extent, Zimbabwe can produce.

1.2.2. Progress Towards Regional Economic Integration

In the SADC region as in other regional economic communities, regional trade and integration arrangements must grapple at varying degrees with three issues: The powers of regional institutions, the effect of their decisions, and dispute resolution.[6] Insofar as regional integration is both the primary reason and goal of SADC, the Southern African regional economic community is miles away from realizing its logic and purpose.

Data from 2013 showed India and China as the largest export and import partners for most SADC countries and over the following decade there has been little development in regional economic activity. The SADC member states with the highest performing economies (i.e., South Africa, Angola, and Tanzania) are integrated more into non-SADC economies, such as China and India than into SADC economies. As well as a customs union there have been plans for a SADC common market. A common market is where states set up a legal regime that removes trade barriers between themselves, establishing common tariff and non-tariff barriers for importers, and allowing for the free movement of labor, capital, and services between themselves. There have been no developments in this area since the early 2010s and the stalling of the SADC customs union, which was a necessary pre-requisite before further economic integration. The official position is that ‘despite current delays in reaching the preceding milestones, SADC is working hard to overcome the challenges presented by the Customs Union, with the long-term goal of establishing a Common Market.’[7]

An additional challenge that confronts SADC is the membership of its member states to other regional economic communities. The problem of multiple memberships is more acute in SADC and East Africa.[8] For example, Tanzania belongs to the SADC, the EAC, and COMESA; Eswatini belongs to the SACU, SADC, and COMESA. The SADC Treaty does not prevent its member states from staying in regional groupings that they joined before they acceded to the SADC Treaty, but the obligations of the distinct and separate communities are sometimes conflicting and often redundant. Membership in other regional economic blocs may be seen as undermining the principal objectives of SADC. Nevertheless, the leaders of SADC, the EAC, and COMESA believe that the African Free Trade Zone will solve the problem created by multiple memberships and regional cooperation schemes‑a ‘promising’ initiative that may not offer much hope of a short-term solution.[9] Third, some member states, notably Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, have voiced concern over the damaging impact of a controversial economic partnership agreement (EPA) with the European Union on regional integration processes. During the 2010s the SADC secretariat has supported the creation of regional trade partnerships between member states. Countries in the Lobito Corridor covering provinces in Angola, the DRC, and Zambia 2023 completed the signing of the Lobito Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency Agreement designed to ensure the development of the transport infrastructure towards the port city of Lobito in Angola.[10] This sits outside the formal framework of SADC but is part of a series of ongoing initiatives by the SADC secretariat to encourage economic cooperation between member states.

2. SADC Law

2.1. Overview

‘SADC law’ refers to the body of principles, rules, and institutions adopted and created by SADC as a regional economic organization to foster regional integration and development in the states party to the SADC Treaty (i.e., member states). SADC law is yet to be entrenched in the curricula of law faculties, legal literature, and public discourse in Africa. The launch of the SADC Law Journal in 2011 was a welcome and huge step towards the entrenchment of SADC law. This introduction to SADC law should be seen along the same lines as an effort to establish SADC law as a distinct field of law. It aims to be a general reference for SADC law.

Most of the SADC law is binding on member states. Article 6(5) of the SADC Treaty places a duty on all member states to accord the SADC Treaty the force of national law. Article 6(5) implies that legal and natural persons must be able to invoke the SADC Treaty in domestic courts, though no party has done it thus far.[11] It remains unclear whether the Treaty should prevail over national laws in case of conflict between the Treaty and national laws. An argument could be made‑based on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties‑that a party to a treaty may not rely on the existence of conflicting provisions in internal law to avoid its obligations under the treaty it voluntarily ratified. Put another way, community law should supersede the internal laws of member states, except their constitutions. Otherwise, states would water down international law obligations as they would be able to avoid them by passing national legislation.

SADC legislation is binding only on the states that are party thereto and once ratified or acceded to, it does not allow for any reservations by the ratifying state. This provision strengthens national policy reform. A member state may withdraw from SADC by serving a written notice of its intention a year in advance to the Chair of SADC, who must inform other member states accordingly. SADC law also comprises non-binding legal instruments, such as model laws and memoranda of understanding (MOUs). These non-binding instruments, or soft law, are usually complex regimes of default rules that SADC member states are free to leave in place or modify to suit local realities but that they tend or are encouraged to adopt as these rules ease the way people do business.

The Treaty and its protocols are the two primary formal sources of SADC law. The Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan 2020-2030), the most powerful soft law in SADC, is the policy framework for the regional integration of SADC. It is not legally binding. Anyway, it is highly persuasive and enjoys considerable political legitimacy. The RISDP envisions that SADC will have a free trade area by 2008 (a target it has achieved), a customs union by 2010 (a target not yet achieved), a common market by 2015, and an economic union by 2018. Other sources of SADC law include international law and resolutions of SADC.

The SADC Tribunal must develop SADC’s jurisprudence with due regard to (1) applicable treaties, (2) the general principles and rules of public international law, and (3) the laws of member states (article 21(b) of the Tribunal Protocol). The three sources for the development of SADC jurisprudence largely duplicate the sources of public international law. Scholarly writings by highly regarded authors are not binding. Given that the SADC community comprises common law (mainly) and civil law countries, it is an unanswered question whether the dispute resolution system of SADC will follow the common law tradition of judicial precedents. Effectively suspended, for all matters but intestate dispute settlements since 2012 the SADC Tribunal does not constitute a source of law.

SADC law organizes the Southern African economic community around nine institutions, namely (1) the Summit of Heads of State or Government (Summit); (2) the Organ on Politics, Defense, and Security (Defense Organ); (3) the Council of Ministers (Council); (5) the Integrated Committee of Ministers; (6) the Standing Committee of Officials (Standing Committee); (7) the Secretariat; (8) the Tribunal; and (9) SADC national committees (SNCs). The Summit is the highest political body of SADC; the Defense Organ is entrusted with peace and stability in the region; the Council superintends the operations of SADC; the Standing Committee advises the Council; the Secretariat executes SADC policies; SNCs represent individual national interests in SADC; and the Tribunal provides a forum for the settlement of disputes concerning the interpretation and application of the SADC Treaty, protocols, and other relevant legal instruments.

The main areas of SADC law are trade, industry, finance, investment, agriculture, infrastructure, services, natural resources, human development, and security. The SADC Treaty calls upon member states to cooperate in all areas necessary to realize regional integration and development based on balance, equity, and mutual benefit. Member states must, through the appropriate SADC institutions, coordinate, rationalize, and harmonize their overall macroeconomic and sectoral policies in the various areas of SADC law.

SADC member states cooperate in each area of SADC law by dint of protocols. Protocols to the Treaty are the legislative acts of SADC. Their role is to spell out the objectives and scope of, and institutional mechanisms for, regional integration and cooperation. The Summit approves protocols on the recommendation of the Council.

Explore the SADC protocols on the SADC website (under documents), including for example:

- Protocol on Trade (1996)

- Protocol on Finance and Investment (2006)

- Protocol on Mining (1997)

- Protocol on Energy (1996)

- Protocol on Forestry (2002)

- Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourses (2000)

2.2. Principles

From the specific rules regulating SADC and its member states emerge a few general principles. The following list indicates some outstanding principles, even if it is not exhaustive.

- Non-discrimination: the foundational principle of SADC trade law is that member states must conduct trade among themselves without discrimination. The most favored nation and national treatment principles are two manifestations of non-discrimination.

- Most-favored nation: member states must apply their tariff rules to all other member states without discrimination.

- National treatment: member states must accord to goods traded within SADC the same treatment as to goods produced nationally in respect of all laws affecting their internal sale, distribution, or use.

- WTO law as normative background: SADC is a ‘free trade area’ within the meaning of the WTO. It is, in terms of Article XXIV (8) (b) of the 1994 General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), an exception to the most-favored nation rule. Thus, SADC must comply with the relevant requirements of GATT as well as the Enabling Clause (which permits trading preferences in favor of developing countries) and Article V of the 1995 General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). It is not possible to fully understand SADC law without a working knowledge of WTO law. To be sure, all SADC member states, except Seychelles, are at the same time WTO members.

- Removal of trade barriers: member states must remove or reduce tariffs, import and export duties, non-tariff barriers, and quantitative import and export restrictions. These measures aim at guaranteeing market access.

- Protection through tariffs: member states may protect their domestic industries only through the use of tariffs.

- International standard: member states may use applicable international standards when setting technical standards, except where these standards would be ineffective and inappropriate in achieving the legitimate objectives of member states. Insofar as SADC law duplicates or replicates international standards, including WTO provisions, SADC should seriously consider briefly summarizing its texts or reducing them to simple references to the corresponding international texts. This move will simplify the language of SADC legal texts and facilitate the deployment of personnel with expertise in WTO law and other relevant fields in the diverse areas of SADC law, thereby saving the additional resources that duplications ordinarily entail.

- Financial cooperation: member states must cooperate and coordinate their policies and strategies in investment, taxation, central banking, and regional capital and financial markets with a view to the achievement of economic development and poverty eradication.

- Mining for development: mining sector activities must contribute to economic development, poverty alleviation, and the amelioration of the standard and quality of life throughout SADC.

- Decisions by consensus: subject to a few exceptions, the institutions of SADC must arrive at decisions by consensus. This is particularly the case for the Summit, the Council, the Standing Committee of Officials, and the institutions brought about by the Mining Protocol. Consensus reinforces the legitimacy of decisions, yet it carries the risk of a hold-out, which may be described as a situation where a party with veto power in a group of persons withholds or withdraws consent to an action that would otherwise benefit the entire group. The consensus requirement effectively gives each SADC member state the power to veto decisions, even those that are beneficial to all SADC member states aside from the vetoing state.

- Since the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development in 2008 there have been ongoing attempts to mainstream gender issues into SADC’s work.

3. The Constitution

Member states drew up and adhered to the treaty of the SADC community in 1992. The Treaty came into force the following year. The SADC Treaty, amended several times, is the founding treaty, the constitution of SADC. It is the fundamental norm, the first organic law of SADC. It enunciates the founding ideals and principles of SADC, states the objectives and obligations of member states, and establishes the institutions that implement the ideals, principles, and objectives of SADC. In short, it frames and shapes big-picture issues.

3.1. Founding Ideals

Regional integration, economic development, and people-centeredness thrust themselves into attention as ideals of the SADC community. Cooperation, both regional and international, is deployed to attain those ideals. Those ideals and the means to attain them are visible in the preamble of the SADC Treaty, which outlines the philosophy behind the creation of the SADC community. Furthermore, since the SADC Treaty is a ‘treaty’ within the meaning of Article 2(1) (a) of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaty, it must be interpreted in good faith by the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the Treaty considering its object and purpose (Article 31(1) of the 1969 Vienna Convention). The ideals formulations state the philosophy, context, objects, and purposes of the Treaty, which in turn serve as aids to the interpretation of the SADC Treaty.

In creating the community, the member states had the resolve to meet the challenges of globalization and to ensure, through common action, the progress and well-being of the people of Southern Africa. They felt a collective responsibility to promote the interdependence and integration of national economies for the harmonious, balanced, and equitable development of the community. They also felt a responsibility to mobilize resources, regional and international, to promote national, interstate, and regional policies, programs, and projects within the framework of regional integration. They recognize that, in an increasingly interdependent world, mutual understanding, good neighborliness, and meaningful cooperation among the countries in the community are indispensable to the realization of the ideals of the SADC community.

SADC puts people in the community at the center of its preoccupation and action. It tries to involve people centrally in the process of development and integration, which is why it emphasizes democratic rights, human rights, the rule of law, and poverty alleviation. Deeper regional integration and sustainable economic growth and development are how SADC will concretize its ideals. For that purpose, SADC is dedicated to securing international understanding, support, and cooperation; observing the principles of international law governing relations between states; and considering the various legal instruments adopted at the continental level. The continental legal instruments to which SADC subscribes are the Lagos Plan of Action (on Africa’s self-sufficiency) and the Final Act of Lagos of 1980 (on the establishment of an African Economic Community by 2000); the Treaty on the establishment of an African Economic Community; and the Constitutive Act of the African Union.

Some principles of the SADC community transcend the narrowly defined interests of regional integration and economic development. Those principles are sovereign equality; solidarity, peace, and security; human rights, democracy, and the rule of law; equity, balance, and mutual benefit; and peaceful settlement of disputes.

3.2. Objectives and Obligations

SADC has set for itself the achievement of several key objectives. The overarching goal running as a thread through these key objectives is the promotion of socio-economic development and the forging of common values and a common agenda. The key objectives of SADC are first to promote sustainable and equitable economic growth and socio-economic development to alleviate poverty, to enhance the standard and quality of life of the people in Southern Africa, and to support the socially disadvantaged through regional integration. The objectives of SADC are, second, to promote common political values, systems, and other shared values, which are transmitted through democratic, legitimate, and effective institutions. A third objective of the SADC community is to consolidate, defend, and maintain democracy, peace, security, and stability. Human rights have been part of this agenda, the 2003 Fundamental Social Rights in the SADC Charter aimed to promote a range of employment rights recognized by the International Labour Organization (ILO). However, since the controversial circumstances surrounding the suppression of the Charter’s jurisdiction (see section 7 below), human rights have increasingly played less of a central role in the organization’s functioning.

A fourth objective is to promote the interdependence of member states and self-sustaining development based on collective self-reliance. Further, SADC has the objective to achieve complementarity between national and regional strategies and programs; and to promote and maximize productive employment and the utilization of resources of the community. It plans to achieve sustainable utilization of natural resources and effective protection of the environment. Finally, SADC plans to strengthen long-standing affinities and links among the peoples of the region; combat HIV and other communicable diseases; and mainstream gender in the community-building process and poverty alleviation in all activities.

It has been said that the objectives and targets of SADC are lofty, unrealistic, and ‘overambitious.’[12] This criticism holds a lot of water. Although prime objectives are ambitious by nature, expressing as they do the desirability of the idealized worlds they imagine, a healthy dose of realism should act as a constraint on the level of ambition displayed in the formulation of objectives.

To fulfill its objectives, however broad, SADC commits to take certain measures concerning the peoples of SADC, the regional economies, and international affairs. Regarding the people of SADC, it encourages people in the region and their institutions to take the initiative to develop economic, social, and cultural ties across the region and to participate fully in the implementation of programs and projects of SADC. It promotes the development of human resources and technology, including the mastery and transfer of technology.

With respect to regional integration, SADC commits to improving economic management and performance through regional cooperation and to harmonize political and socio-economic policies and plans of member states. As states move towards deeper regional integration, the need for effective policy harmonization becomes pressing. Fragmentation would follow if individual member states were free to follow different approaches and apply different rules regarding substantive issues governed by SADC law.[13] Fragmentation would defeat the purpose of the whole economic integration exercise.[14]

SADC undertakes the development of appropriate institutions and mechanisms for the mobilization of requisite resources for the implementation of programs and operations of SADC and its institutions. It also undertakes to make policies aimed at the progressive elimination of obstacles to the free movement of capital and labor, goods and services, and people in the region. Concerning international affairs, SADC must harmonize and coordinate the international relations of member states; secure international understanding, cooperation, and support; and mobilize the inflow of public and private resources into the community.

The achievement of the key objectives of the community requires that member states perform certain obligations over and above the measures they intend to take in terms of the SADC Treaty. Naturally, the first obligation of member states is to adopt adequate measures for the achievement of the key objectives of SADC and the uniform application of the Treaty. The corollary of this obligation is the duty to refrain from taking any measure likely to jeopardize the achievement of SADC’s key objectives or the implementation of the provisions of the SADC Treaty. The SADC Treaty imposes an obligation on member states not to discriminate against any other member states or against any person in member states on the grounds of gender, religion, political views, race, ethnic region, culture, ill-health, disability, and such other ground as may be determined by SADC.

3.3. Policy and Implementation Gaps

SADC law is fraught with a whole slew of deficiencies at both policy and implementation levels. At the policy level, the vast body of SADC rules and principles is not a perfectly coherent and systematic corpus. It is built in a piecemeal, incremental fashion. Equally disturbing is the vague formulation of legal instruments, which may breed disputes and compromise the very principle of legality. The ambiguous language found in myriad provisions in SADC law adds to the perception that SADC law-making is not holistic. Moreover, SADC will have to figure out the extent to which it is wise to copy provisions from relevant WTO Agreements and the space it needs to spare for provisions of SADC law that must speak to the local circumstances in the Southern African community. That said, SADC is a relatively young regional economic community and trade arrangement. When evaluating SADC law, in mind should be kept the fact that SADC is, due to its youth, still experimenting with its policies and their implementation. As regards the vague language of SADC legal instruments, it consciously or unwittingly gives room and flexibility to member states rather than restraining their ability to legislate and act within the framework of SADC law.

Political considerations seem to take over economic and legal concerns. It is fair to say that, regarding economic integration, economics should precede law. Some jurists are of the opinion that a successful economic policy can only be devised by properly trained economic experts; the legal experts intervene later on to transform the economic goals into binding legal instruments.[15] Other jurists think otherwise.[16] Whatever the position one prefers to hold and while it may be somewhat understandable that the economic integration process, which is political at core, will often give priority to political considerations and democratic pressures over matters such as purely legal requirements; it is an expensive strategic mistake to readily sacrifice economic rationality and the long-term economic benefits of regional integration. The decision to disband the SADC Tribunal is one example of such strategic miscalculations.

Regional integration in SADC is further hampered by difficulties in applying the occasionally defective community policies. First, hastily and ‘loosely drafted’ legal instruments complicate implementation and compliance with community laws.[17] SADC suffers from capacity limitations too, including a lack of financial, material, and human resources.

Legions of observers see a serious flaw in the SADC regional trade arrangement through the failure of the SADC Summit of Heads of State and Government to pressure Zimbabwe into complying with the decisions of the SADC Tribunal. The flaw is that compliance with the Tribunal’s decisions is not properly monitored and that no penalties avail for non-compliance.[18] This capacity weakness may be seen as a reflection of the resistance by member states against relinquishing part of their sovereignty to SADC, a feeling that may be behind the deplorable decision by the Summit to suspend temporarily the Tribunal in 2010 following the Campbell v. Zimbabwe saga. With the suspension of the Tribunal at the behest of Zimbabwe, a bad precedent has been set that might encourage other member states to brandish the principle of sovereignty to trump the SADC law obligations they willingly and knowingly assumed.[19] It is indicative of a propensity to put national law before or above community law.[20]

Finally, the SADC Tribunal has not yet heard a trade dispute. This situation may be explained by a lack of awareness of the SADC dispute settlement system, negative attitudes towards litigation, the absence of national legal arrangements on trade remedies (except for South Africa), or the actual neglect by member states regarding the incorporation of SADC law into domestic law.[21]

4. Areas of SADC Law

4.1. Trade and Industry

Article 12 of the SADC Treaty, as amended, lists the following as the eight ‘core areas of integration’:

- Trade, industry, finance and investment (TIFI);

- Infrastructure and service (I&S);

- Food, agriculture, and natural resources (FANR); and

- Social and human development and special programs (S&HD&SP).

The most important area of SADC law is trade. Trade is part of the trade, industry, finance, and investment (TIFI) cluster of the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP). The four parts of TIFI are connected as they all positively impact development and poverty alleviation in SADC. SADC links—through its protocol on trade—trade, industry, finance, and investment. The trade protocol links trade liberalization to a process of viable industrial development and cooperation in finance and investment.

The principal challenge of SADC is the establishment of a common market within a reasonable time to increase the share of SADC exports in global trade. SADC views regional trade as a tool for sustainable economic development to handle this challenge as trade enables deeper regional integration and cooperation and stimulates growth. Regional trade offers a viable alternative to the broken promises of globalization and the WTO.

SADC tries to address supply-side constraints and industrial competitiveness. It also tries to mitigate the incidence of the reduction of tariffs on the development of smaller, landlocked, and less developed member states. As one scholar observed, SADC subscribes to the principle of ‘variable geometry’ or ‘multi-speed integration’, which holds that member states that are willing and able can move on to achieve even deeper levels of integration in some areas.[22]

Globalization—from competitiveness to industrial and product diversification, to productivity—poses a formidable trial of strength to the industrial sector in SADC. That is the reason why SADC industrial policies target the promotion of exports and industrial linkages, efficient import substitution, the improvement of investment climate, and the facilitation of imports of essential goods. The outcomes sought by these policy targets are the enhancement of industrial support services, the equitable distribution of industrial activity, and the adoption of flexible market-oriented exchange rates.

4.1.1. The Trade Protocol

The 1996 Protocol on Trade recognizes that an integrated regional market opens new opportunities for a dynamic business sector. The Protocol on Trade in the Southern African Development Community (Trade Protocol) also considers the 1986-1994 Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations on global trade liberalization. It is the materialization of the desire expressed in the Treaty on the establishment of an African Economic Community (the Abuja Treaty) to put in place sub-regional groupings as building blocks for the creation of an African Economic Community. It provides a framework of trade cooperation anchored to equity, fair competition, and mutual benefit that SADC believes will contribute to the emergence of a workable development community in Southern Africa. Twelve of the then 14 member states signed on 24 August 1996 the Trade Protocol, which came into force on 25 January 2000. The Protocol was notified to the WTO by Tanzania in 2004.

The primary objective of the Trade Protocol is to further liberalize intra-regional trade in goods and services based on fair, mutually equitable, and beneficial trade arrangements, complemented by protocols in other areas. Given the economic inequalities among SADC member states, the Protocol categorizes goods into three classes for the purposes of tariff reduction: Goods A, for which tariffs must be eliminated (i.e., liberalized) immediately; goods B, which must be liberalized progressively; and goods C, which will be liberalized last as they encompass goods that are strategic and/or sensitive to individual member states.[23] Another objective is to ensure efficient production within SADC that leverages the comparative advantages of member states. SADC also plans to improve investment climate; enhance economic development, diversification, and industrialization; and form a free trade area in the region.

Directly drawing many of its provisions from WTO Agreements, the Trade Protocol applies to a vast realm of commercial matters. It covers trade in goods (Part 2); customs procedures (Part 3); trade laws (Part 4); trade-related investment measures (Part 5); trade in services, intellectual property rights, and competition policy (Part 6); and trade development (Part 7). Apart from these substantive issues, the Protocol covers trade relations among member states and with non-member states (Part 8) as well as institutional arrangements and dispute resolution (Part 9). Five annexes implementing the Protocol address rules of origin (Annex I), customs cooperation (Annex II), simplification and harmonization of trade documentation and procedures (Annex III), transit trade and facilities (Annex IV), and trade development (Annex V).

4.1.2. Trade in Goods

4.1.2.1. Removal of Trade Barriers

The first part of the Trade Protocol is devoted to trade in goods and the removal of trade barriers. Subject to a few exceptions and the national treatment rule, the Trade Protocol provides for the removal or reduction of tariffs (article 3), import and export duties (articles 4 and 5), non-tariff barriers (article 6), and quantitative import and export restrictions (articles 7 and 8). The Trade Protocol entrusts a committee of SADC ministers responsible for trade (CMT) with the task of controlling the process for the phased elimination of tariffs and non-tariff technical barriers (NTBs). In doing so, the CMT will have to pay attention to the preferential arrangements between and among member states, the time frame for the elimination of barriers, the adverse impact that the removal of trade barriers may have on member states, and different tariff lines for different products.

Here is a table of SADC national economies, ranked by the estimated value of their exports and imports.

Table 5: Value of SADC Exports and Imports

| SADC Country |

Exports in Million US dollars |

Imports in Million US dollars |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 100,700 | 105,000 |

| 2 | Angola | 69,206 | 22,860 |

| 3 | D.R. Congo | 8,872 | 8,187 |

| 4 | Zambia | 8,589 | 7,361 |

| 5 | Tanzania | 5,997 | 10,330 |

| 6 | Botswana | 6,259 | 6,938 |

| 7 | Namibia | 4,335 | 5,586 |

| 8 | Mozambique | 3,469 | 6,167 |

| 9 | Mauritius | 2,674 | 5,107 |

| 10 | Zimbabwe | 3,314 | 3,607 |

| 11 | Eswatini | 2,005 | 1,643 |

| 12 | Malawi | 1,193 | 1,675 |

| 13 | Lesotho | 1,030 | 1,766 |

| 14 | Madagascar | 640 | 1,958 |

| 15 | Seychelles | 493 | 831 |

| Total | |||

Source: Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook (2013) and World Trade Organization.

The Protocol stipulates that an industrialization strategy to improve the competitiveness of member states accompanies the removal of import duties. However, the Protocol’s prohibition to impose import duties does not prevent member states from imposing across-the-board internal charges. Likewise, the prohibition to impose quantitative import restrictions does not preclude member states from applying a quota system, provided that the tariff rate under such a quota system is more favorable than the rate applied under the Protocol.

SADC could enlist the private sector in thinking up clever ways and means of removing and monitoring trade barriers. This idea is worth considering because a priori it could help solve implementation problems. It may decrease implementation costs for the government by allocating them to parties, i.e., the business community, with a vital interest in and a greater ability to monitor them. This is a solution already used by the East African community with respect to NTBs.[24]

4.1.2.2. Customs Procedures

SADC customs law plays a crucial role in trade. This is so despite the want of adequate customs infrastructure in the region.[25] SADC customs law determines the classification, valuation, and origins of goods to allow member states to apply appropriate tariffs and rates. Part 3 of the Trade Protocol lays down common customs procedures to be followed by member states. It obliges member states to take appropriate measures, including arrangements on customs administration cooperation, to make sure that states apply the Protocol effectively and harmoniously, simplify and harmonize trade documentation and procedures, and grant freedom of transit to goods in transit. Member states harmonize and simplify trade documentation and procedures by, among other things, aligning intra-regional and international documentation on the United Nations Layout Key and by reducing the number of documents to a minimum. The CMT is mandated to establish a Sub-Committee on Trade Facilitation to ensure that member states comply with provisions relating to trade simplification and harmonization.

SADC law also regulates rules of origin. The free movement of goods between SADC member states requires the elimination of tariffs on goods originating within SADC through rules of origin. Rules of origin are an essential ingredient of free trade agreements because they serve to determine which goods are qualified for preferential treatment. Without rules of origin, imports from non-SADC states would enter the free trade area through the country with the lowest external tariffs before moving on to the other SADC members, thereby depriving the latter of customs revenue,[26] a result commonly known as ‘trade deflection’. However, it appears that it is not only trade deflection that should worry SADC policymakers but also the complexity and the heft of the Protocol’s rules of origin, which work as a disincentive for the regional business community trying to apply them.[27]

4.1.3. Trade Measures

Part 4 of the Trade Protocol regulates the many measures that member states may adopt about trade. These measures include standards-related, sanitary, phytosanitary, safeguard, anti-dumping measures, subsidies, and measures for the protection of infant industries. Standards-related measures often raise non-tariff technical barriers to regional trade, which arise from the application of divergent standards and regulations by states in SADC. Incidentally, there is reportedly a surge of these non-technical barriers to regional trade in SADC.[28] Accordingly, the purpose of the Trade Protocol is to harmonize these divergent rules by regionalizing standards.

4.1.3.1. Exceptions

SADC law has developed a generous regime of exceptions to the substantive rules. Article 9 of the Trade Protocol lists exceptions to obligations to remove trade barriers. If it is not done as a means of arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination between member states or as a disguised restriction on regional trade, the prohibition on the imposition of quantitative restrictions does not stop member states from taking some necessary measures. Member states may take measures necessary to protect intellectual property rights; national treasures; public morals and order as well as human, animal, and plant life or health; and to maintain peace and security. Furthermore, they may adopt necessary measures to secure compliance with WTO obligations or any other international obligations; to prevent deceptive trade practices and critical shortages of foodstuffs; to limit the transfer of certain mineral resources; or to conserve natural resources and the environment.

The list of exceptions to the general duty to remove trade barriers is broad. One expert says those exceptions are ‘lavish’ and ‘totally undermine’ the objective of creating a rules-based organization.[29] He maintains that this exceptions regime permits continued protectionism, and advocates the reduction of these exceptions as they usually concern the very goods where partners have a comparative advantage.[30] In 2016 a Protocol Amending Article 3 of the Trade Protocol was signed which allowed more time for states to remove tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade.

4.1.3.2. Standards-Related Measures

Standards-related measures afford member states more flexibility in the protection of health, life, consumers, and the environment while preserving at the same time the compatibility of standards with one another in SADC for the sake of regional trade liberalization. The Protocol allows member states to use applicable international standards when setting technical standards, except where these standards would be ineffective and inappropriate in achieving the legitimate objectives of member states. SADC member states have agreed on the principle of international standards in a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation Standardization, Quality Assurance, Accreditation, and Metrology for the elimination of non-tariff technical barriers to trade within SADC.

The Protocol creates a presumption that a standards-related measure that conforms to an international standard does not unnecessarily impede regional trade. Member states accept as equivalent the technical regulations of other member states, provided that they sufficiently fulfill the objectives of their regulations. Moreover, a member state must, if requested by another member state, seek to promote the compatibility of specific standards or conformity assessment procedures in its territory with the standards and conformity assessment procedures in the territory of the other state. The divergent sanitary and phytosanitary measures on agricultural and livestock production in SADC are primary examples of technical barriers to regional trade. As with standards-related measures in general, the purpose of the Trade Protocol is to harmonize the divergent sanitary and phytosanitary rules by requiring member states to base the rules on international standards, namely the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures.

4.1.3.3. Safeguard Measures

Member states may apply a safeguard measure to a product if they conclude that the product is being imported into their territory in such quantities and such conditions as to cause serious injury to a domestic industry that produces like or directly competitive products. A ‘serious injury’ is defined, by reference to the equivalent WTO provisions, as a significant overall impairment in the position of a domestic industry. The Protocol does not clarify whether key concepts such as ‘product’, ‘industry’, or ‘directly competitive product’, must be defined in terms of the WTO Agreement on Safeguards and the jurisprudence based on it. The guiding philosophy of safeguard measures is to cater to the interests of the member states that suffer from trade liberalization by giving them more time to adjust. Determining when imports have caused a serious injury to a domestic industry requires that members set up strong and effective national institutions capable of making such determinations.[31]

Safeguard measures may also be seen as a safety valve for SADC governments to dilute protectionist pressures from local constituents. Safeguard measures apply to products in a non-discriminatory manner and regardless of the origin of the products within SADC. A member state may apply a safeguard measure only insofar as and for so long as necessary to prevent or remedy serious injury and to ease adjustment. In any event, a safeguard measure must not last more than eight years, which should incidentally induce greater care in the state applying the measure. Furthermore, the Trade Protocol embodies special provisions for the protection of infant industries. Upon application by a member state, the CMT may temporarily authorize that state to suspend trade concessions in respect of like products from other member states.

4.1.3.4. Dumping and Subsidies

The Protocol gives member states the freedom to adopt anti-dumping measures and, with some restrictions, apply countervailing duties. Dumping occurs when a member state exports a product to another member state at a price that is inferior to the one charged in the exporting state or the one charged by a non-member state. It also occurs when the exporting state sells the product at a price below production costs. In essence, anti-dumping laws are designed to counter what the importing state considers to be unfair or trade-distorting practices. However, a consensus is emerging among experts that anti-dumping measures reduce general welfare more than they benefit the economy of the states that impose the measures. This consensus might be the reason for the requirement that a state apply an anti-dumping measure only if a product imported into its territory has caused serious injury to its domestic industry. Regarding subsidies, a member state may provide subsidies to its domestic products as long as they do not distort regional trade or contravene WTO provisions. An importing member state may levy countervailing duties on a product of another member state so that they can offset the effects of subsidies applied by that state on the product.

4.1.4. Services, Intellectual Property and Competition

The Trade Protocol extends its coverage to service industries (e.g., insurance, banking, and securities), intellectual property rights, and competition policies. It obliges member states to formulate policies and execute measures in line with their obligations under the WTO Agreement on Trade in Services to liberalize the services sector in SADC. Likewise, member states must protect intellectual property rights following the WTO Agreement on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. Finally, member states must prohibit unfair business practices and promote competition.

4.1.5. Intra-Regional Trade and Trade with Third Parties

Member states may maintain preferential trade arrangements that existed before the coming into force of the SADC Trade Protocol in 2000. Given the existence of overlapping regional trade arrangements in the Southern African region when SADC was formed, it became necessary to cater to the Southern African countries that were already party to other arrangements.[32] Member states may enter new preferential trade arrangements among themselves if these arrangements are consistent with the SADC Trade Protocol. Henry Mutai says that this provision is an application of the principle of asymmetry, whereby members who wish to liberalize trade amongst themselves more rapidly are allowed to do so.[33] He goes on to say that, although this provision ensures that economically constrained members do not hold back their fellow members, it nevertheless undermines the legally binding nature of the obligations in the Trade Protocol.[34] Mutai’s position is clear, but the same could not be said of his assertion that the provision in question goes against the binding nature of the Protocol.

Article 28 of the Trade Protocol establishes the principle of the most-favored-nation as it enjoins member states to accord most-favored nation treatment to one another. Member states must develop intra-SADC cooperation and coordinate as much as possible trade policies and negotiating positions in relations with third parties and international organizations to advance the objectives of the Trade Protocol. In other words, there is no obligation to negotiate as a unit with third parties.

A member state may also enter preferential trade arrangements with non-SADC states, provided that such arrangements do not frustrate the objectives of the Protocol and that any concession made to non-SADC states is also extended to other SADC member states. As it can be seen, member states’ relations with third parties are a matter intimately linked to the issue of non-discrimination.[35] However, a member state is under no obligation to extend to other member states preferences of another block of which that state was a member at the time of the entry into force of the SADC Protocol.

4.1.6. Committees, Units, and the Forum

The SADC Trade Protocol has instituted (1) a Committee of Ministers responsible for Trade (CMT), (2) a Committee of Senior Officials responsible for trade, (3) a Trade Negotiation Forum (TNF), (4) a Sector Coordinating Unit and (5) a panel of experts. The work of the CMT lies over that of the Committee of Senior Officials in the respect that they both monitor the implementation of the Protocol. Sector Coordinating Units used to oversee the day-to-day implementation of the Protocol, but in March 2001 the Summit changed the law; article 39(1) of the SADC Treaty phased out Sector Coordinating Units and Sectoral Committees.

The CMT oversees the application of the SADC Trade Protocol and the work of any sub-committees. The Committee of Senior Officials reports to the CMT on matters concerning the application of the Protocol, supervises the TNF, and liaises with the CMT. The TNF conducts trade negotiations and reports to the Committee of Senior Officials.

4.2. Finance and Investment

Investment is the second most important area of SADC law after trade. Finance and investment are the two remaining components of the trade, industry, finance, and investment (TIFI) cluster of the RISDP. Investment is another way of going around trade barriers. It is the category of international business transactions that reflects the objective of a company in one economy obtaining a lasting interest in a company resident in another economy.[36] In Plain English, foreign investment arises when a person in a foreign country puts money into a lasting business venture located in another country (i.e., the host country) to make a profit.

4.2.1. The Overall Picture

Southern Africa has registered highs and lows in foreign investments over the past few years. Whereas Africa as a whole benefited from a 5% increase in foreign direct investment (FDI), the Southern African region (excluding the DRC) registered declines in 2012.[37] By contrast, FDI in Southern Africa experienced a significant increase in 2011, after falling by 78% in 2010.[38] The decrease in FDI in 2012 was attributable to declines in both South Africa and Angola, which plunged FDI in SADC from 8.7 billion US dollars in 2011 to 6.3 billion in 2012.[39]

On the other hand, South Africa, and Angola account for the bulk of overseas investments from Southern Africa.[40] South Africa (along with China and India) remains one of the largest developing-country investors in Africa and SADC in particular, holding 16 billion US dollars of investment stock on the continent.[41] FDI in South Africa, SADC’s biggest economy far and away, followed a similar checkered path. In 2012, FDI in South Africa was down, in 2011 up, and 2010 down.

In 2012, Mozambique was the largest beneficiary of FDI inflows in SADC and the second largest in Africa after Nigeria while Angola suffered a 3 billion US dollar drop (see Table 7).

Table 6: Distribution of FDI Inflows by Range in SADC (2012)

| Range | FDI recipients |

|---|---|

| Above 3 billion US dollars |

Mozambique South Africa Dem. Rep. Congo |

| Between 1.0 and 1.9 billion US dollars |

Tanzania Zambia |

| Between 0.5 and 0.9 billion US dollars | Madagascar |

| Between 0.1 and 0.5 billion US dollars |

Zimbabwe Mauritius Namibia Botswana Lesotho Malawi Seychelles |

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, World Investment Report 2013 (2013)

The picture is slightly different and somewhat counterintuitive when it comes to FDI net inflows (new investment inflows minus disinvestment) in 2011.

Table 7: FDI net inflows in SADC (2011)

| SADC country |

FDI net inflows (in million US dollars) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 5,889 |

| 2 | Mozambique | 2,079 |

| 3 | Zambia | 1,981 |

| 4 | Dem. Rep. Congo | 1,596 |

| 5 | Tanzania | 1,095 |

| 6 | Namibia | 968 |

| 7 | Madagascar | 907 |

| 8 | Zimbabwe | 387 |

| 9 | Botswana | 292 |

| 10 | Mauritius | 273 |

| 11 | Seychelles | 138 |

| 12 | Lesotho | 132 |

| 13 | Eswatini | 94 |

| 14 | Malawi | 92 |

| 15 | Angola | -3,000 |

| Total | ||

Source: World Bank (September 2013)

4.2.2. The Legal Landscape

SADC law encourages movement towards regional macroeconomic stability and convergence through prudent fiscal and monetary policies.[42] It provides a framework for cooperation in finance and promotes sound investment policies, savings, investment flows, technology transfer, and innovation in the region. Strategies SADC devised to carry out its finance and investment policies include investment-friendly domestic legislation, macroeconomic convergence, fiscal coordination, current and capital accounts liberalization, reform of payment systems, and resource mobilization through financial institutions. SADC prepared several memoranda of understanding (MOUs) that embrace some of those strategies, including the MOU on Macroeconomic Convergence.

It follows from the policy objectives and their attendant strategies that the pace of integration and harmonization in finance and investment is a paramount concern of SADC policymakers. No less concerning is the necessity of sound macroeconomic and prudent fiscal and monetary policies to rein in inflation, interest rates, deficits, debts, and exchange controls. SADC is also concerned about the difficulties that small and medium enterprises continue to face in accessing credit despite substantial liberalization of the financial sector in the region. Thus, SADC plans to intensify reform of the financial sector, stressing non-bank financial institutions, the participation of women in business, and anti-money laundering initiatives.

4.2.3. The Finance Protocol

The Finance and Investment Protocol 2006 deals with financial cooperation and macroeconomic convergence. The idea of having a protocol on regional cooperation and integration in finance and investment was mooted by SADC finance ministers as early as 1995. The Summit in Maseru (Lesotho) adopted the Finance Protocol on 18 August 2006 when all member states signed it. The Finance Protocol and the Trade Protocol are the two pivots of SADC legislation.

The Finance Protocol incarnates the conviction of SADC that cooperation and coordination of macroeconomic, fiscal, and monetary policies will accelerate growth, investment, and employment in the region. For SADC, macroeconomic stability is a precondition to sustainable economic growth and the creation of a monetary union in the region. The Finance Protocol prizes investment, the private sector, and financial and capital markets for their increasingly important role in productive capacity, higher economic growth, and sustainable development. Mindful of the different economic levels of member states and the need to share equitably the fruits of regional integration, the Protocol underscores the link between investment and trade and the utility of greater regional integration in making the region a more attractive investment destination.

The Finance Protocol spells out its main objective as the harmonization of financial and investment policies of member states to make them conform to the objectives of SADC. It ensures that changes to investment and financial policies in one member state do not lead to undesirable adjustments in other member states. To hit that objective, the Finance Protocol chose to facilitate regional integration, cooperation, and coordination within the finance and investment sectors. It also chose to diversify and expand the productive sectors of the economy and enhance trade to attain sustainable economic development and poverty eradication.

The Protocol contains a menu of how it wants to achieve economic development and poverty eradication: A favorable investment climate, macroeconomic stability and convergence, cooperation in financial matters, creation of frameworks for central banks, and development of capital markets. Cooperation and coordination occupy a place of choice in the achievement of economic development and poverty eradication. Over and above financial cooperation, the Finance Protocol obliges member states to cooperate concerning information and communication technologies among central banks, development finance institutions (DFIs), non-banking financial institutions, stock exchanges, and anti-money laundering. Accordingly, the best part of the Protocol is devoted to the various matters for cooperation. The balance of the Protocol treats macroeconomic convergence, DFIs, anti-money laundering, and the creation of a development fund. These strategic themes are expounded upon in the 11 annexes to the Finance Protocol.

The Finance Protocol earmarks four fields for financial cooperation, namely (1) investment, (2) central banking, (3) regional capital and financial markets, and (4) taxation. Taxation will be dealt with in a future update of this introduction to SADC law.

4.2.4. Investment Cooperation

In the field of investment, the Protocol obliges member states to co-ordinate their investment regimes and cooperate to create a favorable investment climate within SADC as outlined in the first annex to the Protocol (Investment Annex). The Investment Annex specifically aspires to spur economic growth and sustainable development through regional integration and investment promotion agencies (IPAs) in the SADC region. It is guided by the ideals, objectives, and spirit of the Finance Protocol in the facilitation and stimulation of investment flows, technology transfer, and innovation. It is a response to alarms over the low levels of investment in the SADC region despite numerous measures taken to attract investment. It is also an acknowledgment that IPAs need to cooperate among themselves to enhance the attractiveness of SADC, alive to the truism that without effective policies the region will continue to be marginalized on the global trade scene. The Investment Annex is essentially a set of measures for adoption by member states. These measures may conveniently be grouped into promotional, protective, and regulatory categories.

4.2.4.1. Promotion

Arguably, the core promotional activity of member states is, as far as investment in SADC is concerned, to promote (1) trade openness and intra-regional industrial policies as contemplated in the Trade Protocol and (2) regional cooperation in investment, including public-private partnerships (PPPs). This promotional activity insists on the link between trade and investment. To turn SADC into an investment zone, member states must harmonize investment regimes by the best practices, for instance, ratifying the 1965 Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes Between States and Nationals of Other States and the 1985 Convention Establishing the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

There is a duty on member states to promote and admit investments in their territory by putting in place conditions favorable to investments through suitable administrative measures, in particular the expeditious clearance of authorizations. Member states are also invited to encourage PPPs and avoid amending or modifying the terms of their authorizations arbitrarily to the detriment of investors. They should extol the free movement of capital and conclude agreements among themselves to avoid double taxation. They must advance a competition policy in SADC develop local and regional entrepreneurship and enhance regional productive capacity within SADC through the development of skills, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), supporting infrastructures, and other necessary supply-side policies. In the process, member states are free to prioritize industries providing upstream and downstream linkages, and that impact positively on foreign investment inflows and job creation. However, the duty to develop local and regional entrepreneurship does not apply to advantages, concessions, or exemptions resulting from bilateral investment treaties (BITs) or any multilateral arrangement for economic integration in which a member state participates. In 2012 the SADC introduced the SADC Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template (Model BIT) which was not a legally binding document but aimed to provide a template for the construction of investment agreements in the region. This does provide for investment arbitration about disputes under the BIT but at the same time the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCTA), which began preliminary operation in January 2021, is also planning to develop its investment protocol.[43]

Moreover, member states must promote transparency by instituting predictability, confidence, trust, and integrity, which in turn may be accomplished by espousing and enforcing open and transparent policies, practices, laws, regulations, and procedures as they relate to investment. Member states must permit investors to hire key personnel, regardless of nationality, if the host state or SADC does not have those skills and if such sourcing builds local capacity through skills transfer. States must promote the optimal use of their natural resources in a sustainable and environmentally friendly fashion. Finally, member states are to promote investment promotion agencies (IPAs). They must ensure their IPAs operate in tune with national and regional development priorities; advise the host states, the private sector, and other stakeholders on trade and investment policies; and raise awareness of investment opportunities, incentives, and laws, using regular exchange of information.

4.2.4.2. Regulation and Protection

The Investment Annex enunciates the right of member states to regulate. Member states may exercise their right to regulate in the public interest and to adopt, maintain, or enforce any measure that it considers appropriate to ensure that investment is undertaken in a manner sensitive to health, safety, or environmental concerns. The flip side of the right of member states to regulate is that investors must abide by the regulations, laws guidelines, and policies of the states. Member states may enact regulations that provide conditions favorable to the least developed countries of SADC in the process of economic integration based on non-reciprocity and mutual benefit. They must ensure that the least-developed countries of SADC receive effective preferential treatment.

A good portion of the Investment Annex is devoted to the protection of investments. Investments and investors must enjoy fair and equitable treatment in the territory of any member state, and that treatment must not be less favorable than that granted an investor from a non-member state. Member states are forbidden to nationalize or expropriate except for a public purpose, under due process of law, on a non-discriminatory basis, and subject to the payment of prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. This provision protects foreign investors from political risks by restraining the right of member states to take or otherwise interfere with property and property rights. It affects that restraint by imposing requirements that lawful takings be for a public purpose, non-discriminatory, and compensatory to the investors aggrieved by the takings. It is however possible for member states to give preferential treatment to qualifying investments and investors to fulfill national development objectives. In addition, member states must make sure that investors can repatriate investments and return on investments.

Foreign investors must have the right of access to the courts, judicial and administrative tribunals, and other competent authorities for the redress of their investment-related grievances, such as expropriation claims or differences over the determination of compensation for expropriation. Member states and foreign investors must settle investment disputes amicably and at any rate exhaust local remedies before they can submit their disputes to international arbitration if either the state or the investor so wishes. Should either party choose to go for international arbitration, they may refer the dispute to the SADC Tribunal, the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), an international arbitrator, or an ad hoc arbitral tribunal. If parties cannot agree on any of those dispute settlements for three months after written notification of the claim, they must submit the dispute to arbitration under the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).

4.2.5. Central Banking and Financial Markets

4.2.5.1. Central Banking

A note on the 2009 SADC Central Bank Model Law explains that the Model Law embodies general principles to facilitate the operational independence of SADC central banks and the harmonization of their legal and operational frameworks and sets standards of accountability and transparency in those frameworks.[44] The long title of the Model Law is to ‘update and re-enact’ the national legislation of the central bank in SADC.

The Model Law is a comprehensive outline, a recipe for national legislation on the operations of a central bank. It addresses the functions and objectives of SADC central banks, currency, international reserves, payment systems, reporting requirements, the relationship of central banks with government and other financial institutions, monetary policy committees, and institutional arrangements.

The Model Central Bank Law retains the twin functions of central banking, namely monetary and financial stability. For the Model Law, the primary objective of the central bank is to ‘achieve and maintain price stability.’ Central banks must be independent but may support the general economic policy of the government. In pursuing its primary objective, the central bank must articulate monetary policy, including exchange rate policies; hold gold and foreign exchange reserves; regulate matters relating to the domestic currency; and act as a fiscal agent to the government and as a banker to the government and banks alike.

4.2.5.2. Financial Markets

The Finance Protocol provides harmonization and cooperation in three areas. It first obliges SADC member states to harmonize national laws and work together in the regulation of non-banking financial institutions and the facilitation of collaboration between the regulators of those financial institutions. Second, the Protocol obliges member states to harmonize national laws and cooperate in developing the capacity of national capital and financial markets with the ultimate purpose of creating a single regional capital and financial market. Third, member states must facilitate cooperation between their respective stock exchanges.

4.3. Mining

The RISDP states that mining and agriculture account for more than 50% of total SADC GDP. Apart from South Africa and Mauritius, which have sizeable manufacturing sectors, SADC member states heavily rely on mining, agriculture, or services. Given the economic prominence of these sectors, this introduction to SADC law zeroes in on the Mining Protocol (1997) as this is the only one of those three vital areas for cooperation on which SADC has enacted a protocol.

The point of SADC mining policies is the development of an economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable regional mining sector capable of meeting regional challenges and ensuring long-term competitive growth for the sector. To that end, SADC member states have since 2000 been harmonizing their mining policies to improve investment climate, information flows, and a commercially viable small-scale mining industry with greater participation of women. Since harmonization is nonetheless still unfinished business, the priority of SADC mining policy is to complete that process. Other challenges include constraints in the form of barriers to the flow of factors of production, something that slows down investment in the mining sector.