Guide to Legal Research in Honduras

By José Miguel Álvarez and Jessica Ramos

José Miguel Álvarez obtained a law degree from Universidad de Navarra, Spain. He also obtained an LL.M in Corporative Law from Universidad Complutense, Madrid and a Degree in IP Law from Universidad de Salamanca. He is a member of the Honduras Bar Association; currently he is an associate of Consortium-J.R Paz & Asociados.

Jessica Ramos obtained a law degree from UNITEC, Honduras. She is a member of the Honduras Bar Association; currently she is an associate of Consortium-J.R Paz & Asociados.

Published February 2007

Read the Update!

Table of Contents

1. General Information

1.1 Historic Background

The Pre-Columbian city of Copán is a locale in extreme western Honduras, in the department of Copán near the Guatemalan border. It is a major Maya city that flourished during the classic period (150-900 A.D). It has many beautiful carved inscriptions and stelae. The ancient kingdom, named Xukpi, flourished from the 5th century AD to the early 9th century, with antecedents going back to at least the 2nd century AD. The Maya civilization changed in the 9th century AD, and they stopped writing texts at Copán, but there is evidence of people still living in and around the city until at least 1200 AD. By the time the Spanish came to Honduras, the once great city-state of Copán was overrun by the jungle.

On his fourth and final voyage to the New World, in 1502, Christopher Columbus reached the coast of Honduras, and landed near the modern town of Trujillo, somewhere along the Guaimoreto Lagoon, and had his priests say mass. After the Spanish discovery, Honduras became part of Spain’s vast empire in the New World, within the Kingdom of Guatemala. The Spanish ruled Honduras for approximately three centuries.

Honduras declared independence from Spain on September 15, 1821 with the rest of the Central American provinces. In 1822 the Central American State was annexed to the newly declared Mexican Empire of Iturbide. The Iturbide Empire was overthrown in 1823 and Central America separated from it, forming the Federation of the United Provinces, which disintegrated in 1838. The states of the United Provinces became independent nations.

Much of the country’s history has been shaped and conditioned by the economic enclave established mainly by the U.S. mining and banana companies at the turn of the last century. Between 1882 and 1954, the New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Co., the oldest in the Republic, produced over $60 million worth of gold and silver from the Rosario mines, near Tegucigalpa. By the mid-1960s, these mines had become virtually non-productive and much of the mining operation concentrated in the country’s northern and western region.

The quintessential “banana republic”, Honduras became a foreign enclave as a result of Anglo-American control over its railroads, mining industry and banana production in the late 1800’s. U.S. banana companies were to dominate the country for many years. After the turn of the century, The United Fruit Company and the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company expanded their control over the rich alluvial plains of Honduras’ Atlantic coast. By 1929, the United Fruit Company owned or controlled 650,000 acres of the best arable land, along with railroads and ports. The banana operations were run like private chiefdoms, in which the companies kept order and crushed labor organizing with their own security forces or by calling in U.S. troops, until a major strike in 1954 caused many labor reforms to be implemented.

Bananas came to represent some 88% of Honduran exports, focusing on the economic activity of the country almost wholly in the Atlantic coast region. Due to this, Honduras is the only Central American country whose economic center is not the capital (Tegucigalpa) but a town near the Caribbean coast (San Pedro Sula). A second result was that the population of the coastal regions became predominantly West Indian, since the U.S. companies preferred to hire English speaking laborers. In addition to those recruited from the Caribbean islands, there was a Garifuna (Black Carib) population concentrated on the Bay Islands off the coast and in the town of Trujillo, where the government granted them 7,000 hectares of land in 1901.

Honduras was distinguished from its neighbors by the totality of the banana companies’ control. In contrast to El Salvador, Costa Rica and Guatemala, no native groups or companies rose to make fortunes in coffee exports. Instead, the U.S. companies controlled the government, financing political parties which conspired against each other. The U.S. also began training a Honduran army and air force, which were commanded by the U.S. officers and served primarily to protect the interests of the banana companies.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Honduras joined the Allied Nations on the 8th of December, 1941. Less than a month later, on the first day of 1942, Honduras, along with 25 other governments signed the Declaration by United Nations.

The so-called Soccer War of 1969 was fought with El Salvador. There had always been border tension between the two countries after Oswaldo López Arellano, past military dictator and president of Honduras, blamed the poor economy on the large number of immigrants from El Salvador. From that point on the relationship between El Salvador and Honduras had been a sour one. It reached a low when El Salvador met Honduras for a three-round football elimination match as a preliminary to the World Cup. Tensions escalated, and on July 14, 1969, the Salvadoran army launched an attack against Honduras. The Organization of American States negotiated a cease-fire which took effect on July 20, with the Salvadoran troops withdrew in early August. The war lasted approximately 100 hours and led to an arms race between the two countries.

Twenty years of military rule and de facto governments ended in the 1982 with the enactment of a new Constitution and the beginning of a new Republican government. At this time, the United States established a military presence in Honduras with the purpose of supporting the anti-Sandinista Contras fighting the Nicaraguan government and to support the El Salvador military fighting against the FMLN guerrillas. Though spared the bloody civil wars wracking its neighbors, the Honduran army quietly waged a campaign against leftists.

Hurricane Fifí caused severe damage while skimming the northern coast of Honduras on September 18 and 19, 1974. Many years later, in October 1998, Hurricane Mitch devastated the country and severely damaged its economic system.

Twenty-five years of Republican government have stabilized the country and as a young democracy, Honduras is growing in the new world order marked by globalization.

1.2 Politics

A Presidential and general election was held on November 27, 2005. Manuel Zelaya of the Liberal Party of Honduras (Partido Liberal de Honduras: PLH) won, with Porfirio Pepe Lobo of the National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras: PNH) coming in second. The PNH challenged the election results, and Lobo Sosa did not concede until December 7. Towards the end of December the government finally released the total ballot count, giving Zelaya the official victory. Zelaya was inaugurated as Honduras’ new president on January 27, 2006.

Honduras has five registered political parties: PNH, PLH, Social Democrats (Partido Innovación Nacional y Social Demócrata: PINU-SD), Social Christians (Partido Demócrata-Cristiano: DC), and Democrat Unification (Partido Unificación Democrática: UD). The PNH and PLH have ruled the country for decades. In the last years, Honduras has had five Liberal presidents: Roberto Suazo Córdova, José Azcona del Hoyo, Carlos Roberto Reina, Carlos Roberto Flores and Manuel Zelaya, and two Nationalists: Rafael Leonardo Callejas Romero and Ricardo Maduro. The elections have been full of controversies, including questions about whether Azcona was born in Honduras or Spain, and whether Maduro should have been able to stand given he was born in Panama.

In 1963 a military coup was led against the democratically elected president Ramón Villeda Morales and a military junta was established to rule the country without holding elections until 1981, with varying executive leaders. In this year Roberto Suazo Córdova (LPH) was elected president and Honduras transferred from a military authoritarian regime to an electoral democracy.

In 1986, José Azcona del Hoyo was elected via the “Formula B,” when Azcona did not obtain the majority of votes. However, 5 Liberal candidates and 4 Nationalists were running for president at that time, and the “Formula B” required all votes from all candidates from the same party to be added together. Azcona then became the president. In 1990, Rafael Callejas Romero won the election under the slogan “Llegó el momento del Cambio,” (The time for Change has arrived), which was heavily criticized for resembling El Salvador’s “ARENAs” political campaign. Callejas Romero gained a reputation for illicit enrichment. Callejas has been the subject of several scandals and accusations in the last decade. In 1998, during Carlos Flores Facusse’s mandate, Hurricane Mitch hit the country and all indications of economic growth were washed out in a period of 5 days.

In 2004 separate ballots were used for mayors, congress, and president. Many more candidates were registered for the 2005 election.

The Nationalist and Liberal parties are distinct political parties with their own dedicated band of supporters, but some have pointed out that their interests and policy measures throughout the 23 years of uninterrupted democracy have been very similar. They are often seen as primarily serving the interests of their own members, who receive jobs when their party gains power and lose them again when the other party does so. Both are seen as supportive of the elite who own most of the wealth in the country, with neither of them promoting socialist ideals, even though in many ways Honduras is run like a democratic version of an old socialist state, still with some price controls and nationalized electric and land-line telephone services.

However, President Maduro’s administration “de-nationalized” the telecommunications sector in a move to promote the rapid diffusion of telecom services to the Honduran population. As of November 2005, there were around 10 private-sector telecom companies in the Honduran market, including two mobile phone companies.

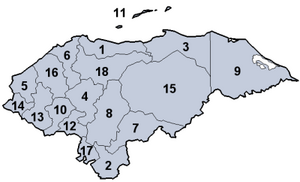

1.3 Administrative Division

The largest province by area is Olancho department and by population is Francisco Morazán department, where the capital city of Tegucigalpa is located; the smallest in both area and population is the Islas de la Bahía department, where the strength of the country’s tourism industry is located in the island of Roatán.

|

1.4 Geography

Honduras borders the Caribbean Sea on the north coast and the Pacific Ocean on the south through the Gulf of Fonseca. The climate varies from tropical in the lowlands to temperate in the mountains. The central and southern regions are relatively hotter and less humid than the northern coast. The Honduran territory consists mainly of mountains (~81%), but there are narrow plains along the coasts, a large undeveloped lowland jungle region, La Mosquitia, in the northeast and the heavily populated lowland San Pedro Sula valley in the northwest. In La Mosquitia lies the UNESCO-world heritage site Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, with the Coco River dividing the country from Nicaragua. See Rivers of Honduras. Natural resources include timber, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, antimony, coal, fish, shrimp, and hydropower.

2. The Constitution

The 1982 Constitution consists of a preamble and 379 articles divided into eight titles that are further divided into forty-three chapters. The first seven titles cover substantive provisions delineating the rights of individuals and the organization and responsibilities of the Honduran State. The last title provides for the constitution’s implementation and amendment.

The organization of the Honduran state, national territory and international treaties are covered in Title I of the Constitution. As stated in Article 4, “The government is republican, democratic and representative” and “composed of three branches: legislative, executive and judicial, which are complementary, independent, and not subordinate to each other.” In practice, however, the executive branch has dominated the other two branches of government. Article 2, which states that sovereignty originates in the people, also includes a provision new to the 1982 Constitution that labels the supplanting of popular sovereignty and the usurping of power as “crimes of treason against the fatherland.” This provision can be considered an added constitutional protection of representative democracy in a country in which the military has a history of usurping power from elected civilian governments.

Title II addresses nationality and citizenship, suffrage and political parties, and provides for an independent and autonomous Superior Elections Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo Electoral–TSE) to handle all matters relating to electoral acts and procedures. Provisions regarding nationality and citizenship are essentially the same as in the 1965 constitution, with one significant exception. In the 1965 document, Central Americans by birth were considered “native-born Hondurans” after one year of residence in Honduras and after completing certain legal procedures, but in the 1982 constitution (Article 24), Central Americans by birth who have resided in the country for one year are Hondurans by naturalization. With regard to the electoral system, Article 46 provides for election through proportional or majority representation.

Individual rights and guarantees for Honduras citizens are addressed in Title III. This section covers such matters as social, child, and labor rights; social security; and health, education, culture, and housing issues. Different from the 1965 constitution is the chapter devoted entirely to “rights of the child.”

The rights of habeas corpus and amparo are provided for in Title IV, which also addresses the constitutional review of laws by the Supreme Court of Justice and cases when constitutional guarantees may be restricted or suspended.

Title V outlines the branches and offices of the government and their responsibilities, and spells out the procedure for the enactment, sanction, and promulgation of laws. It covers the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government; the Superior Accounts Tribunal (TSC, Comptroller Office) and the Directorate of Administrative Probity, both of which are auxiliary but independent agencies of the legislative branch; the Office of the Attorney General, the legal representative of the Honduran state; the offices of the ministers of the cabinet, with no fewer than twelve ministries; the civil service; the departmental and municipal system of local government; and guidelines for the establishment of decentralized institutions of the Honduran state. Different from the 1965 constitution, the terms of legislators and the president are four years, instead of six years. Another new feature focuses on the development of local government throughout the country. Article 299 states that “economic and social development of the municipalities must form part of the national development program,” whereas Article 302, in order to ensure the improvement and development of the municipalities, encourages citizens to form civic associations, federations, or confederations.

The chapter on the judiciary also contains several changes from the 1965 constitution. The changes, according to one analysis, appear to bring the administration of justice closer to the people. Article 303 declares that “the power to dispense justice emanates from the people and is administered free of charge on behalf of the state by independent justices and judges.”

The Supreme Court of Justice has fifteen principal justices, increased from the nine principals and seven alternates it provided before its reform in 2001.

Title V also includes a chapter covering the armed forces, which consists of the “high command, army, air force, navy, public security force, and the agencies and units determined by the laws establishing them.” The president retains the title of general commander over the armed forces, as provided in Article 245 (16). Orders given by the president to the armed forces, through its commander in chief, must be obeyed and executed, as provided in Article 278. The armed forces, however, is under the direct command of the commander in chief of the armed forces (Article 277); and it is through him that the president performs his constitutional duty relating to the armed forces. According to Article 285, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces is the armed forces consultative organ.

The nation’s economic regime, covered in Title VI, “is based on the principles of efficiency in production and social justice in the distribution of wealth and national income, as well as on the harmonious coexistence of the factors of production.” As provided in Article 329, the Honduran state is involved in the promotion of economic and social development, subject to appropriate planning. The title also includes provisions on currency and banking, agrarian reform (which is declared to be of public need and interest), the tax system, public wealth, and the national budget.

Title VII, with two chapters, outlines the process of amending the constitution and sets forth the principle of constitutional inviolability. The constitution may be amended by the National Congress after a two-thirds vote of all its members in two consecutive regular annual sessions. However, several constitutional provisions may not be amended. These consist of the amendment process itself, as well as provisions covering the form of government, national territory, and several articles covering the presidency, including term of office and prohibition from reelection.

2.1 Constitutional Law

Honduras constitutional law has two main procedures that can be described as follows:

- Procedures primarily concerned with the protection of constitutional supremacy through general and concrete procedural remedies against the unconstitutionality of the laws.

- Procedures primarily concerned with the protection of constitutional individual rights, one being the writ of habeas corpus that guarantees the right to personal freedom, and the other the writ of “amparo” that protects the rest of fundamental rights from arbitrary governmental acts.

Regarding the first, that is procedures concerned with constitutional supremacy, Articles 184 through 186 of the Constitution set forth two types of unconstitutionalities of the laws. First a general unconstitutionality and second an unconstitutionality for concrete cases. The difference between both is that the latter is only binding on the parties whereas the former has full effects throughout the whole legislative system. Both remedies have the purpose of guaranteeing the principle of constitutional supremacy set forth in the Honduran Constitution.

The two remaining procedures, concerned with the protection of individual fundamental rights, are governed by Articles 182 and 183 of the Constitution. The basic difference is that habeas corpus primarily guarantees individual freedom whereas the writ of amparo guarantees all fundamental rights. Both writs are similar in the sense that they protect individuals in their fundamental rights from arbitrary acts of government.

Except for the case of the general unconstitutionality of the law, all other procedures such as the amparo, habeas corpus and unconstitutionality in concrete cases require a direct interest in order to have standing. This is either by invoking an injury or a threat of an injury to individual rights as guaranteed in the Constitution. An injury occurs in any case in which the law or application of the law imposes an immediate, direct and personal obligation that abrogates or modifies rights legally vested in the person of the complainant.

Constitutional Law in Honduras is not only governed by the Constitution but also by the Ley de Justicia Constitucional (hereinafter Law on Constitutional Justice) decree number 244-2003 enacted by Congress. This legislation provides a detailed regulation of the constitutional procedures, enforcement mechanisms, and their conditions of admissibility and spheres of competence.

2.2 The Supreme Court of Justice as a Constitutional Court

Honduras has no separate or autonomous Constitutional Court. A special Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice handles and rules on the writs and procedures referred above. The Constitutional Chamber (“Sala de lo Constitucional”) is specifically created under Article 7 of the Law on Constitutional Justice and is composed of five Justices designated by the Supreme Court of Justice.

3. Structure of Government, Administrative and Election Law

Honduras is a democratic republic formed by the state organs set forth in the Constitution. For administrative purposes it is divided into eighteen departments which are each divided into municipalities. The departmental government is entrusted to a Governor appointed by the President and his duties are administrative only.

The municipal government is carried out in an autonomous manner and is exercised by a Municipal Council presided over by a Mayor, all members being elected by popular vote. The Law of Municipalities, decree 134-90 of Congress sets forth in detail the attributes of municipalities. The constitution sets forth several provisions regarding the municipalities. According to Article 299, the economic and social development of the municipalities must form part of the nation’s development plans. Each municipality is also to have sufficient communal land in order to ensure its existence and development. Citizens of municipalities are entitled to form civic associations, federations, or confederations in order to ensure the improvement and development of the municipalities. In general, income and investment taxes in a municipality are paid into the municipal treasury.

3.1 The Executive branch

The executive branch in Honduras, headed by a president who is elected by a simple majority, has traditionally dominated the legislative and judicial branches of government. According to the constitution, the president has responsibility for drawing up a national development plan, discussing it in the cabinet, submitting it to the National Congress for approval, directing it, and executing it. He or she directs the economic and financial policy of the state, including the supervision and control of banking institutions, insurance companies, and investment houses through the National Banking and Insurance Commission. The president has responsibility for prescribing feasible measures to promote the rapid execution of agrarian reform and the development of production and productivity in rural areas. With regard to education policy, the president is responsible for organizing, directing, and promoting education as well as for eradicating illiteracy and improving technical education. With regard to health policy, the president is charged with adopting measures for the promotion, recovery, and rehabilitation of the population’s health, as well as for disease prevention. The president also has responsibility for directing and supporting economic and social integration, both national and international, aimed at improving living conditions for Hondurans. In addition, the president directs foreign policy and relations, and may conclude treaties and agreements with foreign nations. He or she appoints the heads of diplomatic and consular missions.

With regard to the legislative branch, the president participates in the enactment of laws by introducing bills in the National Congress through the cabinet ministers. The president has the power to sanction, veto, or promulgate and publish any laws approved by the National Congress. The president may convene the National Congress into special session, through a Permanent Committee of the National Congress, or may propose the continuation of the regular annual session. The president may send messages to the National Congress at any time and must deliver an annual message to the National Congress in person at the beginning of each regular legislative session. In addition, although the constitution gives the National Congress the power to elect numerous government officials (such as Supreme Court justices, the comptroller general, the attorney general, and the director of administrative probity), these selections are essentially made by the president and rubberstamped by the National Congress.

3.2 Legislative Branch

The legislative branch consists of the unicameral National Congress elected for a four-year term of office at the same time as the president. The constitution, as amended in 1988, establishes a fixed number of 128 principal deputies and the same number of alternate deputies. If the principal deputy cannot complete his or her term, the National Congress may call the alternate deputy to serve the remainder of the term.

The National Congress conducts regular annual sessions beginning on January 25 and adjourning on October 31. These sessions, however, may be extended. In addition, special sessions may be called at the request of the executive branch through the Permanent Committee of Congress, provided that a simple majority of deputies agrees. A simple majority of the total number of principal deputies also constitutes a quorum for the installation of the National Congress and the holding of meetings. The Permanent Committee of Congress is a body of nine deputies and their alternates, appointed before the end of regular sessions, that remains on duty during the adjournment of the National Congress. The National Congress is headed by a directorate that is elected by a majority of deputies, which is headed by a president (who also presides over the Permanent Committee of Congress when the National Congress is not in session) and includes at least two vice presidents and two ministers.

The constitution sets forth forty-five powers of the National Congress, the most important being the power to make, enact, interpret, and repeal laws. Legislative bills may be introduced in the National Congress by any deputy or the president (through the cabinet ministers). The Supreme Court of Justice and the Superior Elections Tribunal may also introduce bills within their jurisdiction. In practice, most legislation and policy initiatives are introduced by the executive branch, although there are some instances where legislation and initiatives emanate from the National Congress. A bill must be debated on three different days before being voted upon, with the exception of urgent cases as determined by a simple majority of the deputies present. If approved, the measure is sent to the executive branch for sanction and promulgation. In general, a law is considered compulsory after promulgation and after twenty days from being published in the official journal, La Gaceta. If the president does not veto the bill within ten days, it is considered sanctioned and is to be promulgated by the president.

If the president vetoes a measure, he must return it to the National Congress within ten days explaining the grounds for disapproval. To approve the bill again, the National Congress must again debate it and then ratify it by a two-thirds majority vote, whereupon it is sent to the executive branch for immediate publication. However, if the president originally vetoed the bill on the grounds that it was unconstitutional, the bill cannot be debated in the National Congress until the Supreme Court renders its opinion on the measure within a timeframe specified by the National Congress. If an executive veto is not overridden by the National Congress, the bill may not be debated again in the same session of the National Congress.

If the National Congress approves a bill at the end of its session, and the president intends to veto it, the president must immediately notify the National Congress so that it can extend the session for ten days beyond when it receives the disapproved bill. If the president does not comply with this procedure, he must return the bill within the first eight days of the next session of the National Congress.

Certain acts and resolutions of the National Congress may not be vetoed by the president. Most significantly these include the budget law, amendments to the constitution, declarations regarding grounds for impeachment for high-ranking government officials, and decrees relating to the conduct of the executive branch

Regarding government finances, the National Congress is charged with adopting annually (and modifying if desired) the general budget of revenue and expenditures based on the executive branch’s proposal. The National Congress has control over public revenues and has power to levy taxes, assessments, and other public charges. It approves or disapproves the formal accounts of public expenditures based on reports submitted by the comptroller general and loans and similar agreements related to public credit entered into by the executive branch.

The legislative branch has two auxiliary agencies, the Superior Accounts Tribunal (Comptroller Office) and the Directorate of Administrative Probity, both of which are functionally and administratively independent. The Superior Accounts Tribunal (Comptroller Office) is exclusively responsible for the post-auditing of the public treasury. It maintains the administration of public funds and properties and audits the accounts of officials and employees who handle these funds and properties. It audits the financial operations of agencies, entities, and institutions of the government, including decentralized institutions. It examines the books kept by the state and accounts rendered by the executive branch to the National Congress on the operations of the public treasury and reports to the National Congress on its findings. The Directorate of Administrative Probity audits the accounts of public officials or employees to prevent their unlawful enrichment.

3.3 Judicial Branch

The judicial branch of government consists of a Supreme Court of Justice, courts of appeals, courts of first instance (Juzgados de Letras), and justices of the peace. The Supreme Court, which is the court of last resort, has fifteen principal justices. The Supreme Court has fourteen constitutional powers and duties. These include the appointment of judges and justices of the lower courts and public prosecutors; the power to declare laws to be unconstitutional; the power to try high-ranking government officials when the National Congress has declared that there are grounds for impeachment; and publication of the court’s official record, the Gaceta Judicial. The court has three chambers– civil, criminal, and labor–with three justices assigned to each chamber.

Organizationally below the Supreme Court are the courts of appeals. These courts are three-judge panels that hear all appeals from the lower courts, including civil and commercial, criminal, labor, administrative and constitutional or habeas corpus cases. To be eligible to sit on these courts, the judges must be attorneys and at least twenty-five years old. The next levels of courts are the first instance courts, distributed throughout the country, which serve as trial courts. The first-instance courts cover both civil/commercial and criminal cases, labor, family, administrative, domestic violence and juvenile cases. The judges, who must be at least twenty-one years old, hold degrees in juridical science.

The lowest level of the court system consists of justices of the peace distributed throughout the country. Each department capital and municipalities with populations of more than 4,000 are supposed to have two justices, and municipalities with populations less than 4,000 are supposed to have one justice of the peace. Justices of the peace handling criminal cases act as investigating magistrates and are involved only in minor cases. More serious criminal cases are handled by the first instance courts. Justices of the peace must be more than twenty-one years of age, live in the municipality where they have jurisdiction, and have the ability to read and write. Political patronage has traditionally been the most important factor in appointing justices of the peace, and this practice has often led to less than qualified judicial personnel, some of whom have not completed primary education.

3.4 Attorney General

Closely associated with the judicial system and the administration of justice in Honduras is the Office of the Attorney General, which, as provided in the Constitution, is the legal representative of the State, representing the State’s interests. Both the attorney general and the deputy attorney general are elected by the National Congress for a period of four years, coinciding with the presidential and legislative terms of office. The Attorney General is expected to initiate civil and criminal actions based on the results of the audits of the Superior Accounts Tribunal (Comptroller Office). The law creating the Office of the Attorney General was first enacted in 1961.

3.5 Public Prosecutor’s Office

The Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministerio Público) is an independent, autonomous, and apolitical organization, not under either the Supreme Court or the Office of the Attorney General. The Public Prosecutor General is appointed by the National Congress. An independent entity, functionally unattached to all three branches of Government, the Public Ministry was instituted on January the 6th, 1994, through Legislative Decree No. 228-93. Its main functions are the prosecution of all crimes and felonies, to ensure full compliance by all with the Constitution and the law of the land, and to represent, to defend and to protect the general interest of society.

Its objectives are:

- To Represent, defend and to protect the general interests of the Honduran society;

- To Collaborate and to watch for the expedite, straight and efficient administration of justice, especially in the criminal environment, carrying out the investigation of the crimes until discovering the criminals and to file before the competent courts the law enforcement, by means of the exercise of the public criminal action.

- To Watch for the respect and fulfillment of the rights and constitutional guarantees and by the same rule of the Constitution and the Laws;

- To Fight the drug trafficking and the Corruption in any of its forms;

- to Investigate, to verify, to determine the property ownership and the integrity of the national goods of public use, as well as the appropriate, rational, and legal use of the hereditary goods of the State that have been given to any individual and in if it’s the case, to exercise or to coax the corresponding legal actions;

- To collaborate in the protection of the environment, of the ecosystem, of the ethnic minorities, preservation of the cultural and archaeological patrimony and other collective interests;

- To Protect and to defend all goods of first need and of public utility;

- In contribution with other public or private agencies, to watch for the respect of Human Rights.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office has jurisdiction in all the Republic of Honduras, and all persons and legal entities have access without any restriction of age, sex, religion etc.

Such access is direct and does not require representation or legal sponsorship. The legal matters carried out by the Public Prosecutor Office are free, as well as the ones carried out before the same one.

3.6 Human Rights Commissioner

Honduras has a National Human Rights Commissioner who acts as an “Ombudsman”, having the mission to promote the integrity and security of all Hondurans. The Human Rights Commissioner is a direct and free alternative for mediation with the State Government and the citizens, especially when human rights have been violated.

Within its functions are:

- To secure the fulfillment of the rights and guarantees established in the Constitution of the Republic, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other treaties and covenants ratified by Honduras.

- Lending immediate attention and monitoring any accusation of violation of human rights;

- Request to any authority, office, agency or institution, concrete information on violations of human rights;

- Review that the acts and resolutions of the Public Administration are harmonious with the content of Treaties, covenants and international agreements in matter of human rights ratified by Honduras;

- To give to the local authorities the observations, recommendations and advice for the proper legal application.

The Human Rights Commissioner may act by his own means or by request in any case originated on abuse of power, law error, negligence or omission, and disobedience to courts´ rulings. Also he may act in regards to conflicts between citizens (except in cases of domestic violence) and it may also act with respect to a problem that is pending a judicial or administrative resolution.

3.7 Administrative Law

Relations between the administrative government and its employees are governed by the Civil Service Law. In addition, Foreign Affairs servants and Judiciary officers have specific Civil Service Laws. In the case of autonomous decentralized state organs, these are governed by their own constitutive regulations. The latter would be the case of the organic law of the National Bank and Insurance Commission, Social Security Institute, etc.

For the settlement of disputes within the administrative realm, remedies must be exhausted before a case can be presented before a judge. In that case the Contentious-Administrative first-instance court is empowered to hear litigation deriving from acts or resolutions made by the public administration, municipalities, and decentralized, autonomous or semi-autonomous entities in the exercise of their own powers, as well as in cases of claims based on contracts or concessions of an administrative nature.

3.8 Electoral Process

The president is elected along with a vice president for four-year terms of office beginning on January 27. The president and the vice president must be Honduran by birth, more than thirty years old, and enjoy the rights of Honduran citizenship. Additional restrictions prohibit public servants and members of the military from serving as president. Commanders and general officers of the armed forces and senior officers of the police or state security forces are ineligible. Active-duty members of any armed body are not eligible if they have performed their functions during the previous twelve months before the election. The relatives (fourth degree by blood and second degree by marriage) and spouse of each military officer serving are also ineligible, as are the relatives of the president and the presidential delegates.

The President, who is the representative of the Honduran state, has a vast array of powers as head of the executive branch. The Constitution delineates forty-five presidential powers and responsibilities. The president has the responsibility to comply with and enforce the constitution, treaties and conventions, laws, and other provisions of Honduran law. He or she directs the polices of the state and fully appoints and dismisses secretaries and deputy secretaries of the cabinet and other high-ranking officials and employees (including governors of the eighteen departments) whose appointment is not assigned to other authorities.

To be elected to the National Congress, one must be a Honduran by birth that enjoys the rights of citizenship and is at least twenty-one years old. There are a number of restrictions regarding eligibility for election to the National Congress. Certain government officials and relatives of officials are not eligible if the position was held six months prior to the election. All officials or employees of the executive and judicial branches, except teachers and health-care workers, are prohibited from being elected, as are active duty members of any armed force, high-ranking officials of the decentralized institutions, members of the TSE, the attorney general and deputy attorney general, members of the TSC, and the director and deputy director of administrative probity.

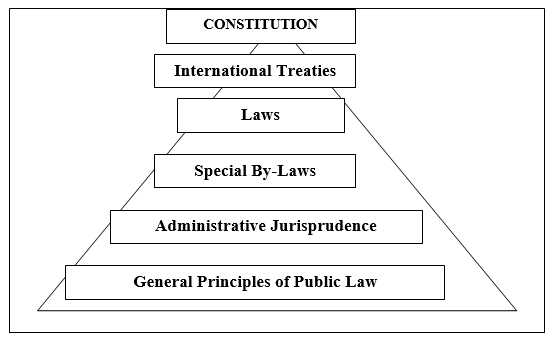

4. Sources of Law

According to Honduras Civil Code, specifically Articles 1 and 2, the sources of law recognized in the Honduras legislation are the Law as a primary source, Jurisprudence and Legal Doctrine, together with common uses and customs in cases in which the law makes specifically reference to them. Common uses and popular customs may only be used as a source and therefore applicable law as long as they are not contrary to morals, public order and are duly proven.

4.1 Legislation

Honduras is in fact a civil law country; ergo legislation is considered the primary source of law which is established through codified law, special laws and written administrative regulations. Thus, laws are only valid once the enactment procedure is completed and come into force once they are published in the Official Gazette, such as is established in Articles 213 through 221 of the Constitution.

It is an exclusive attribute of members of the National Congress, the President, by means of his Secretaries of State or cabinet members, as well as the Supreme Court of Justice and the Supreme Elections Tribunal, in matters of their competence, to have an initiative of law. No project of law shall be definitively voted, unless three debates have taken place in three different days; except in urgent matters, in which case it may be voted and approved by simple majority of the members of Congress present.

Every project of law that has been approved by the National Congress will be passed to the Executive Branch no later than three days after being voted to be sanctioned and be promulgated. In case the Executive finds any inconvenience to sanction the project of law, it will veto it and return it to the National Congress within the next ten days, explaining the reasons of why it disagrees. If its not objected within these period it will be held as sanctioned and it shall be promulgated. When the Executive power returns the vetoed project, the National Congress will enter into a new deliberation on it and if this is ratified by two thirds of the votes, it shall pass it to the Executive power once again and it should be promulgated right away.

Codes, Laws, Decrees and Cases can all be found in print; they are published in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, by OIM publishing House oimeditorial@cablecolor.hn (tel. 504 990 4106). Also official copies of these codes are available through the Gaceta, the Official Gazette of the Republic of Honduras.

4.2 Treaties

The Constitution of the Republic of Honduras contains seven provisions that define the internal status of treaties within Honduras. Honduras holds and incorporates as its own the principles and practices of International Law that make reference to human solidarity, self-determination, non-intrusion, consolidation of peace and universal democracy.

Arbitration and judicial judgments of international character are considered mandatory in Honduras. Every international treaty celebrated by Honduras with third parties must be previously approved by the National Congress, before the ratification by the Executive in order to become enforceable and part of the internal legal system.

When a disposition of an international Treaty is contrary to a Constitutional provision, it must be approved following the same procedure that is applicable when reforming the Constitution. In cases of conflict between a Treaty and ordinary law, the Treaty shall prevail as long as it has follows the procedure to be enforceable in Honduras.

Article 205 of the Constitution, interjection 30, states that it is an attribute of the members of the legislative power to approve or reject every international treaty that the executive branch enters into.

4.3 Attributes of Powers concerning Treaties

Article 245 of the Constitution establishes that the President of Honduras has the attribute to fulfill and make mandatory the treaties that are entered into with third parties, as well as the attribute to enter into treaties and agreements, ratifying them prior approval of the National Congress.

5. Foreign Direct Investment

The Constitution of Honduras accords the private sector freedom to invest in any sector of the economy, reserving to the State certain basic industries for security reasons or public purpose. The Investment Law accords equal treatment to companies established in the country, whether national or foreign, and nondiscrimination on participation in corporations.

The foreign investor is excluded from small-scale trade and industry as defined in Article 3 of the Administrative Regulation to the Investment Law. Foreign investors may not engage in these activities unless they become naturalized Hondurans, and provided reciprocity exists in their respective countries (Article 49, Regulation to the Investment Law).

The Principle of International Reciprocity also exists in Honduras with respect to air services and small-scale trade and industry.

Foreign investment is not subject to performance requirements except in the following cases: a) companies resorting to fiscal incentive regimes to promote exports; b) requirements in respect of rules of origin and tariff treatment are established in trade conventions or agreements signed by Honduras; and c) requirements for the preservation of public health and the conservation of natural resources.

5.1 Rights and protection of foreign investment

The Foreign investor is given the same treatment as the national investor in all economic sectors as well as most favored nation treatment by giving him equal treatment to the foreign investor from any other country.

5.2 Property Protection

The Honduran Constitution contemplates takings or expropriations in cases of collective use, social benefit or public interest, all duly justified; as well as for purposes of agrarian reform or urban development, or any other purpose in the national interest. When the property constitutes a latifundium or the lands are idle or not farmed or under exploited or when the holdings have been fragmented into minifundia resulting in poor use or destruction of natural resources or low production yields; or in the case of rural holdings owned by two or more persons and when the holdings are exploited indirectly (Agrarian Reform Law).

The laws of the national telecommunications company (HONDUTEL), the National Water Service (SANAA) and the National Electricity Company (ENEE), each allow for easements, rights of way and expropriations to carry out their work.

The value of the property will be equal to the average value declared by the owner for the purposes of the payment of property tax during the three years prior to the date of the expropriation or taking; if no value was declared, the average declared value for other property located in the same area will be used as the base value.

With respect to payment, the Honduran Constitution and the Agrarian Reform Law provide that compensation should be in cash and Agrarian Debt Bonds redeemable annually. Authorities can not take possession of expropriated asset prior paying compensation, because until the expropriating institution makes payment, property transfers may not be made in the Public Register.

5.3 DR CAFTA

On August 5, 2004, the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic signed the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA). The treaty was ratified by Honduras and became effective March 2005. It is a comprehensive and reciprocal trade agreement, which distinguishes it from the unilateral preferential trade program enacted by Congress of the United States as part of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI), as amended. It provides detailed rules that govern market access of goods, services trade, government procurement, intellectual property, investment, labor, and environment. Enacting DR-CAFTA has required legislative action in Honduras, mainly the Law for the Implementation of DR CAFTA effective April 2006. One of the most significant chapters arising from the CAFTA-DR is Chapter 10 on Foreign Direct Investment. This agreement represents the most detailed and precise set of rules to form part of the Honduran legislation on foreign investment with Parties to the Treaty.

6. Research Tools

6.1 Government Internet Sites

- Presidency of the Republic

- Secretary of Foreign Affairs

- Secretary of Defense

- Secretary of Agriculture, Food and Livestock

- Secretary of Education

- Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources

- Secretary of Culture and Sports

- Secretary of Public Finance

- Secretary of Public Health and Social Assistance

- Secretary of Labor and Social Prevention

- Secretary of Communications, Infrastructure and Housing

- Secretary of Security

- Secretary of Commerce and Industry

- Secretary of the Interior

- Secretary of the Presidency

- Secretary of Tourism

Legislative Branch.

Judiciary Branch.

Other State organs

- Secretaría Técnica y de Cooperación

- Procuraduría General de la República

- Tribunal Superior de Cuentas

- Ministerio Público

- Comisionado Nacional de los Derechos Humanos

- Banco Central

- Comisión Nacional de Bancos y Seguros

- Dirección Ejecutiva de Ingresos

- Comisión Nacional de Telecomunicaciones

- Alcaldía Municipal del Distrito Central

- Instituto de la Propiedad

- Registro Nacional de las Personas

- Registro de Propiedad Industrial

6.2 Honduras Bar and Legal Associations

6.3 Law Schools

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras (UNAH)

- Universidad Tecnológica Centroamericana

- Universidad Católica de Honduras Nuestra Señora de la Paz

- Universidad de San Pedro Sula

- Universidad José Cecilio del Valle

- Universidad Tecnológica de Honduras

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma en el Valle de Sula

6.4 Books and Publications

Sites containing Honduran laws:

- www.leyesvirtuales.com;

- www.hondurasinfo.com;

- www.Hondudirectorio.com;

- www.honduraseducacional.com/leyes.htm

6.5 Newspapers

6.6 Participation in International Organizations

International organization participation: BCIE, CACM, FAO, G-24, G-77, IADB, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICFTU, ICRM, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Interpol, IOC, IOM, ISO (correspondent), ITU, LAES, LAIA (observer), NAM, OAS, OPANAL, OPCW, PCA, RG, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, UPU, WCL, WCO, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO, UN-WTO